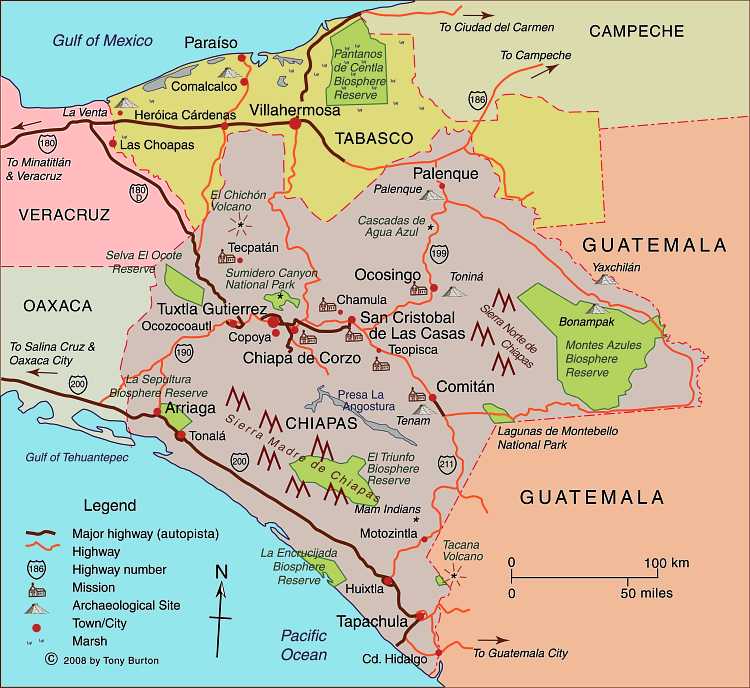

The Mexican Mam (there are also Guatemalan Mam) first settled in Chiapas in the late nineteenth century, mainly in the deforested mountains of the eastern part of the state. They had virtually disappeared from view as a cultural group by 1970, having lost most of their traditional customs. Today, the 8,000 or so Mam, living close to the Guatemala border, have shown that it is possible for some indigenous groups to re-invent themselves, to secure a stronger foothold in the modern world.

Mexican policies from 1935-1950 towards Indian groups were focused on achieving acculturation, so that the groups would gradually assume a mestizo identity. It was widely held at the time that otherwise such isolated groups would inevitably be condemned to perpetual extreme poverty. To the Mam, this period is known as the “burning of the clothes”. Almost all of them lost their language, traditional dress, and methods of subsistence, and even their religion, in the process. Indeed, for a time, the term Mam never appeared in any government documents.

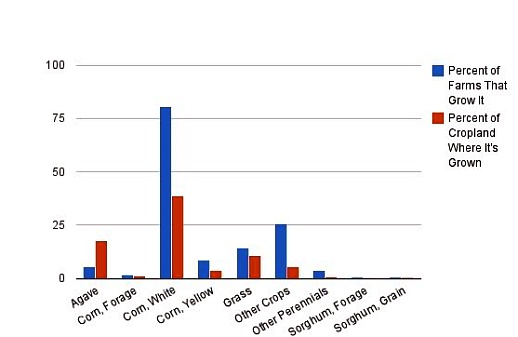

From 1950-1970, the Mexican government opted for a modernization approach, building roads (including the Pan-American highway) and attempting to upgrade agricultural techniques. The mainstay of the regional economy is coffee. During this period, most Mam were peasant farmers, subsisting on corn and potatoes, gaining a meager income by working, at least seasonally, on coffee plantations. Working conditions were deplorable, likened in one report to “concentration camps”. Plantation owners forced many into indebtedness. The Mam refer to this period as the time of the “purple disease”: onchocercosis, spread by the so-called coffee mosquito. Untreated, it leads to depigmentation, turning the skin purple, skin lesions and blindness. Reaching epidemic proportions, it devastated the Mam peasants who had no access to adequate medical services.

From 1950-1970, the Mexican government opted for a modernization approach, building roads (including the Pan-American highway) and attempting to upgrade agricultural techniques. The mainstay of the regional economy is coffee. During this period, most Mam were peasant farmers, subsisting on corn and potatoes, gaining a meager income by working, at least seasonally, on coffee plantations. Working conditions were deplorable, likened in one report to “concentration camps”. Plantation owners forced many into indebtedness. The Mam refer to this period as the time of the “purple disease”: onchocercosis, spread by the so-called coffee mosquito. Untreated, it leads to depigmentation, turning the skin purple, skin lesions and blindness. Reaching epidemic proportions, it devastated the Mam peasants who had no access to adequate medical services.

After 1970, the Mam gradually re-found themselves, as official policy was to foment a multicultural nation. Some, especially many who had become Jehovah’s Witnesses, migrated northwards forming several small colonies, promoted by the government, in the Lacandon tropical rainforest on the border with Guatemala. Others, spurred on by Catholic clergy influenced by liberation theology, began agro-ecological initiatives.

For instance, one 1900-member cooperative, ISMAM (Indigenous People of the Motozintla Sierra Madre), specialized in the production of organic coffee. ISMAM’s agro-ecological initiatives benefited from the advice of the community’s elders and rescued many former sound agricultural practices, such as planting corn and beans alongside the coffee bushes to avoid the degradation that can result from monoculture. It halted the application of agrochemicals, and studied methods of organic agriculture and land restoration. Its coffee, adroitly marketed, commands premium prices, double those of regular coffee sold on the New York market. The Mam have effectively taken advantage of modern technology, from phones to e-mail, to overcome their isolation, and compete on their own terms, developing export markets in many European nations, as well as the U.S. and Japan.

At the same time, the Mam have re-invented their cultural identity and helped revive the language and traditional forms of dance. They have also rewritten their past. The revisionist version is that they always had the utmost respect for nature and had always lived in harmony with the environment. In reality, as historical geographers have demonstrated, this was not always the case. Whatever the historical reality, the defense of the earth, nature and their culture is now central to the Mam.

The main source for this post is R. Aída Hernández Castillo’s Histories and Stories from Chiapas. Border Identities in Southern Mexico (University of Texas Press, 2001).

Link to original article on MexConnect

From 1950-1970, the Mexican government opted for a modernization approach, building roads (including the Pan-American highway) and attempting to upgrade agricultural techniques. The mainstay of the regional economy is coffee. During this period, most Mam were peasant farmers, subsisting on corn and potatoes, gaining a meager income by working, at least seasonally, on coffee plantations. Working conditions were deplorable, likened in one report to “concentration camps”. Plantation owners forced many into indebtedness. The Mam refer to this period as the time of the “purple disease”:

From 1950-1970, the Mexican government opted for a modernization approach, building roads (including the Pan-American highway) and attempting to upgrade agricultural techniques. The mainstay of the regional economy is coffee. During this period, most Mam were peasant farmers, subsisting on corn and potatoes, gaining a meager income by working, at least seasonally, on coffee plantations. Working conditions were deplorable, likened in one report to “concentration camps”. Plantation owners forced many into indebtedness. The Mam refer to this period as the time of the “purple disease”: