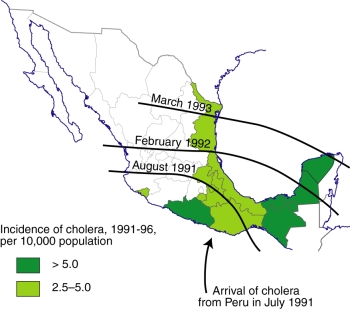

When Mexico braced herself for the imminent arrival of cholera from South America in 1991, many people believed that the disease had never previously been known here. However, during the 19th century, there were several outbreaks, including the epidemic of 1833 in which more than 3,000 people died in the city of Guadalajara alone.

A meeting of public health officials in January 1833 stressed the need for public areas to be regularly cleaned. This meeting called for the construction of six carts, to be used each night for removing the excrement left on street corners, since not all the houses had “accesorios” (toilets). This proposal reveals the unsanitary conditions which prevailed in Guadalajara at that time.

The epidemic struck in July, and peaked in August, when more than 200 people died of the disease each day. Sporadic cases dragged on into early 1834.

The shout of “Aguas!” (“Waters!”) as a warning of imminent danger, still used in many contexts today, actually dates back to when there was no sewage collection or provision. It was used to warn passers-by in the street below that the contents of “night buckets” were about to be emptied onto their heads…

In 1849 the city of Guadalajara feared a second epidemic. The authorities published a list of precautions that they considered essential, and a list of the “curative methods for Asiatic cholera.” At that time, the only major hospital in the city was the Hospital Belén. Its rival, the San Juan de Díos hospital, was “small and poorly constructed, insufficiently clean, and careless in waste disposal.”

The situation was made worse because the San Juan De Díos River was little more than an open sewer running through the center of the city. This river is now entirely enclosed and runs directly beneath the major avenue of “Calzada Independencia.”

Only two methods of sewage disposal were in use in 1850. Some houses took their sewage to the nearest street corner, where it was collected by the nightly cart for subsequent removal from the city. Other (higher class) houses deposited their sewage in open holes in the ground which allowed the wastes to separate, with the liquids permeating into the subsoil and the solids accumulating. Not exactly ideal in terms of public health!

The town council called for the construction of more of these latrines and for the activities of the night carts to be reduced.

The council also advocated increasing the air circulation in the city and simultaneously fumigating it. Authorities in Cuba had tried something similar in 1840, when they had spread resin, and fired batteries of cannons simultaneously, all over Havana! It was believed that the air housed cholera and other diseases and that it could directly affect the organism, through its “miasmas.”

The “Cuban solution” is tried in Guadalajara

In 1850, the epidemic began and the Guadalajara council voted to try the Cuban solution. On August 7th , at the height of the epidemic, fireworks, artillery and everything else were ignited – even the church bells were rung – in order to stimulate air movement and purification , “to increase the electricity in the air and reduce the epidemic.”

During the 1833 epidemic, various industrial plants, including ones making soap, starch and leather, had been closed, though no regulations were ever passed for their subsequent improvement. This time, in 1850, more drastic measures were taken. Tanneries had to construct their own watercourses, and their water was not allowed to collect and stagnate by bridges. Soap works were transferred out of the city completely. Despite these efforts, many stagnant pools of water would have lain on the city’s poorly constructed cobblestone streets: pools of water just waiting for an outbreak of cholera.

The police force was given the power to supervise everyone’s adherence to the regulations. Inspectors were appointed for each district or barrio to see that all “night activities” (carts included) terminated before 8:00 a.m., that sewage water was not used for the irrigation of plants, that gatherings were not too large, and that billiard, lottery and society halls all closed at the start of evening prayers.

A group of doctors was obliged to give its services free to anyone who needed medical help. The doctors apportioned the city among themselves and were told by the town council that they would be paid for their services as soon as council funds permitted. The main idea, of course, was to help the poor, perhaps not so much from any altruistic motives but to avoid any inconvenience to the rich!

Fortunately, any new outbreak of the disease in modern Guadalajara will be handled very differently to these 19th century epidemics. The excellent modern medical facilities in the city, and the large number of qualified doctors, mean that anyone unlucky enough to contract the disease should be able to get adequate treatment ensuring a full and speedy recovery.

This is an edited version of an article originally published on MexConnect

Click here for the complete article

Note: The diffusion of cholera in Mexico during the 1991-1996 epidemic is discussed, alongside a map showing the incidence of the disease, in chapter18 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico.

Geo-Mexico also includes an analysis of the pattern of HIV-AIDS in Mexico, and of the significance of diabetes in Mexico.