The Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), an independent, non-profit research organization dedicated to promoting a better understanding of the social and economic factors that develop a more peaceful society, has released its first Mexico Peace Index. The 2013 Mexico Peace Index (MPI) is based on a similar methodology as previous IEP indices, including the United States Peace Index and the United Kingdom Peace Index; however specific measures were included to better reflect the specific Mexican cultural and national context.

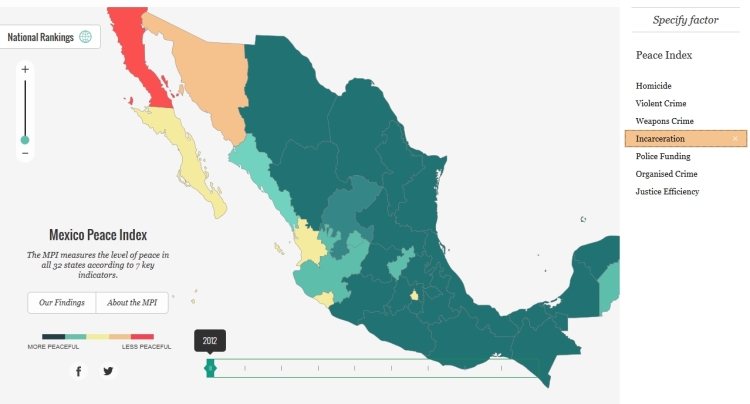

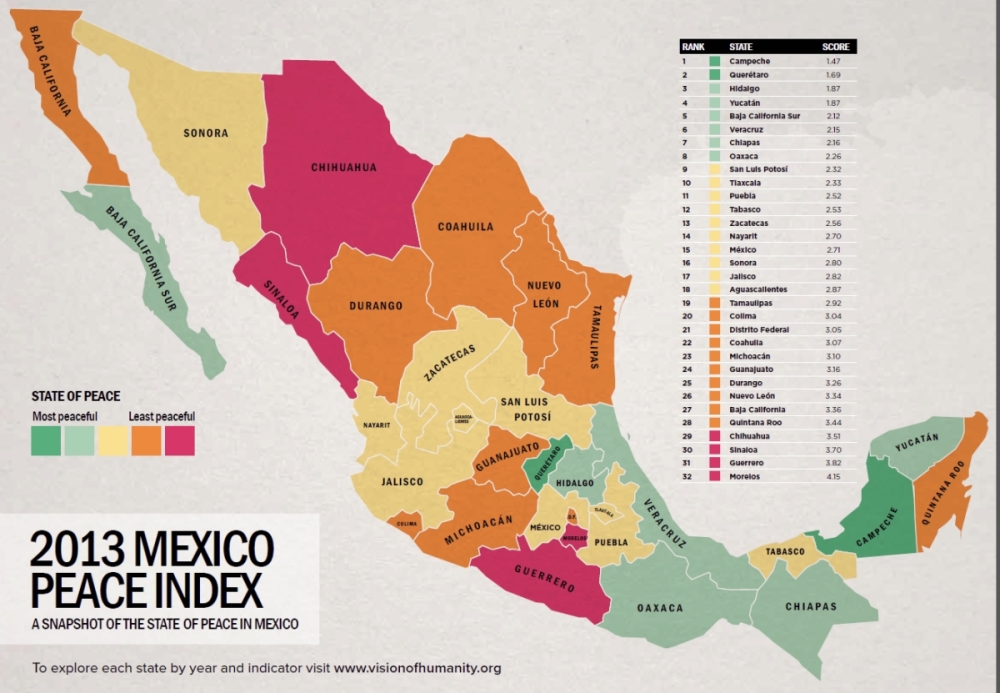

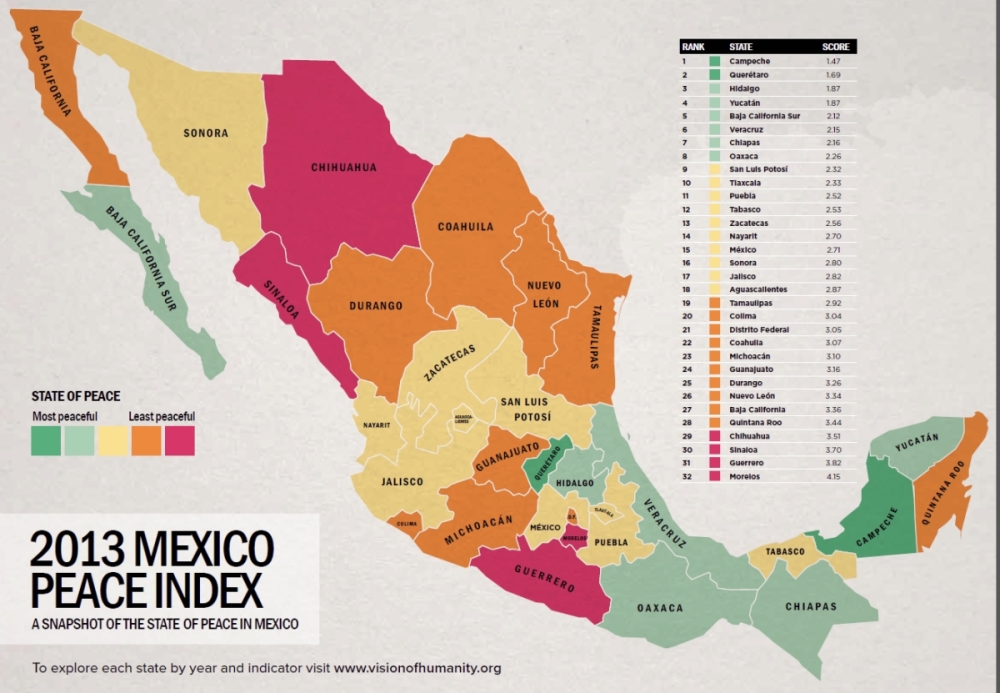

For the Mexico Peace Index, seven indicators were used to analyze peace: homicide rates, violent crime, weapons crime, incarceration, police funding, efficiency of the justice system, and the level of organized crime.

The study was performed with the guidance of an Expert Panel representing various institutions such as IMCO, CIDE, Mexico Evalua and INEGI. The Mexico Peace Index 2013 uses data provided by INEGI and the Executive Secretariat of the National Public Security System (SESNSP).

Mexico Peace Index. Credit: Institute for Economics and Peace.

The headlines

- Mexico Peace Index finds that peace improved 7.4% in past two years

- The two-year improvement in peace was primarily driven by a 30% decrease in organized crime

- Most peaceful states experienced an annual GDP growth of more than double the least peaceful states

- Oaxaca, Chiapas, and Yucatan have the most improved levels of peace in the past decade

- Mexico has the greatest potential in the world to overcome its current levels of violence and build a more peaceful society, with a strong business environment and high levels of human capital

- The eastern region of Mexico is the most peaceful; the northern region the least

The 2013 MPI provides a comprehensive assessment of peace in Mexico detailing the level of peace in each of the 32 states over the last 10 years and an analysis of the costs associated with violence as well as the socio-economic dimensions associated with peace.

The study finds that there was a 7.4% improvement in Mexico’s peace scores in the last two years, driven by decreases in organized crime, violent crime, and weapons crime. However, over the past 10 years Mexico experienced a marked increase in direct violence, with peace declining by 27%. A key factor was the 37% increase in the homicide rate since 2007.

The study finds that there was a 7.4% improvement in Mexico’s peace scores in the last two years, driven by decreases in organized crime, violent crime, and weapons crime. However, over the past 10 years Mexico experienced a marked increase in direct violence, with peace declining by 27%. A key factor was the 37% increase in the homicide rate since 2007.

The 2013 MPI presents comparisons between the states and the regions of Mexico, and finds that the states with the highest levels of peace are: Campeche, Queretaro, Hidalgo, Yucatan and Baja California Sur while the five least peaceful states are: Morelos, Guerrero, Sinaloa, Chihuahua, and Quintana Roo.

The study finds that Oaxaca, Chiapas and Yucatan experienced the most substantial increases in their levels of peace during the last decade. Oaxaca improved its score by 22% and Chiapas by 17%. These states were found to be relatively peaceful in comparison with other areas of Latin America and North America. Campeche, for example, has a level of peace comparable with the states of New Mexico and Delaware in the United States.

Regionally, the research finds that the eastern region of Mexico is the most peaceful, while the northern region is the most violent.

Analysis of federal funding to state police (Fondo de Aportaciones para la Seguridad Publica) finds that increases in police funding are related to crime reporting rates, with increased funding improving the public’s relationship with the police.

The direct cost of violence to the Mexican economy is 3.8% of GDP, while the indirect costs amount to 12% for a total 2.49 trillion pesos (15.8% of GDP). Under optimal conditions, if there was no violence in Mexico, the economy would have the potential to improve by up to 27%. This figure includes direct and indirect costs and the additional flow-on economic activity that would eventuate from new money being added to the economy. The study highlights that if all the states of Mexico were as peaceful as Campeche, the most peaceful state in the country, Mexico would reap an economic benefit of 2.26 trillion pesos.

The most peaceful Mexican states in 2003 experienced the strongest economic performance in 2012. Over the past 10 years, these states’ GDP increased by 9% versus 4% in the least peaceful states.

Steve Killelea, founder and executive chairman of IEP said: “Compared to other countries with a similar level of conflict and development, Mexico has the greatest potential to increase its peace on account of the strength of the structures, attitudes and institutions that sustain peace in the long term.” He added that: “This research aims to provide the evidence base and data for a broader policy debate about how to reduce violence in Mexico”.

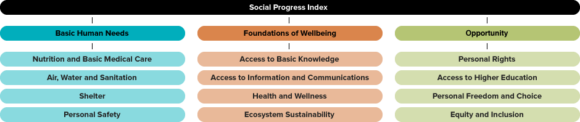

Mexico’s standing in regards to positive peace is encouraging: the country has a strong business environment, performs well on measures of human development, and ranks better than world averages on education.

Factors impacting peace in Mexico

It is well known that the increase in the levels of violence in Mexico has been a consequence of the war against drug trafficking, but there are other key factors at play.

The number of firearms smuggled into Mexico increased substantially during the last decade, almost three times higher in the period 2010-2012 than between 1997 and 1999.

As a consequence, the weapons crime indicator, which measures the number of offenses involving the use of weapons, recorded a significant increase of 117% per 100,000 people during the last decade.

The measure of the efficiency of the justice system has recorded a significant deterioration. In some states up to 95% of homicides remain unpunished.

In addition, the public perception of corruption is very high and one of the greatest challenges facing Mexico.

Prison capacity is overstretched with a Mexico Evalua 2013 report stating that 52.4% of prisons in the country are over-crowded and house 74% of the prison population in Mexico.

There is a high level of unreported crime in Mexico. According to data from the National Survey of Victimization and Perception of Public Safety 2012 (ENVIPE), only 19% of theft, 10% of fraud and 10% of extortion cases are reported.

It is important to address all of these key challenges in order to reduce violence and realise the social and economic benefits of peace in Mexico.

This post is the text of a press release from the Institute for Economics and Peace. For more information about the report, visit http://visionofhumanity.org/#/page/news/812 and http://visionofhumanity.org/#/page/indexes/mexico-peace-index

The full 96-page report – available here – is well worth reading and offers many more insights into the changes taking place in Mexico.

Related posts: