While writing Geo-Mexico, the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico, we were surprised to find there were no books in English about the geography of Mexico aimed at readers in the upper grades of high school or beginning years of college. On the other hand, we knew of several books about Brazil aimed at that level, most of them published in the U.K.. Why are there more geography books about Brazil than about Mexico?

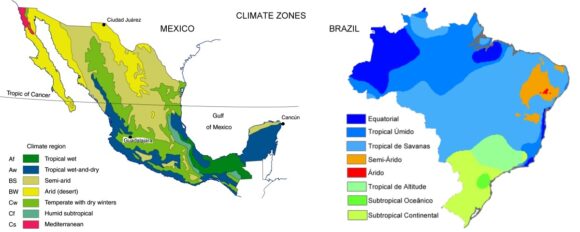

One attraction of Brazil to geographers is that the spatial patterns of activities in that country are far simpler to describe, map and analyze, than their counterparts in Mexico. For example, compare these two maps of climate zones:

This makes it easier to teach about the spatial patterns of Brazil than Mexico. Even though regional geography largely disappeared from U.K. schools in the 1970s, most examination syllabi for the equivalent of Grade 13 still required the study of countries at contrasting levels of economic development. Brazil was a relatively popular choice to represent either (initially) an LEDC (Less Economically-Developed Country) or (more recently) an emerging economy or “middle-income” country. Naturally, this led to textbooks based on Brazil.

If further evidence were needed that British schools have tended to ignore Mexico, then look no further than a recent article in Geography, the flagship journal of the U.K.’s Geographical Association, the leading subject association for all teachers of geography in the U.K.

Quoting its website,

The Geographical Association (GA) is a subject association with the core charitable object of furthering geographical knowledge and understanding through education. It is a lively community of practice with over a century of innovation behind it and an unrivalled understanding of geography teaching. The GA was formed by five geographers in 1893 to share ideas and learn from each other. Today, the GA’s purpose is the same and it remains an independent association.”

The Autumn 2015 issue of Geography includes “Twenty-five years of Geography production”, an article by Diana Rolfe analyzing the content of the last 25 years of the publication. One particular section caught our eye. Rolfe lists the number of times that specific places are referred to over that time in the journal’s “place-based articles”.

The Autumn 2015 issue of Geography includes “Twenty-five years of Geography production”, an article by Diana Rolfe analyzing the content of the last 25 years of the publication. One particular section caught our eye. Rolfe lists the number of times that specific places are referred to over that time in the journal’s “place-based articles”.

The analysis shows that 78 countries were referred to in the past 25 years. The most frequently mentioned country (no surprise here) is the U.K., with (139 articles over the past 25 years). The next most frequently mentioned country is South Africa (27 mentions), followed by China (16), France (12), Australia (10), Hong Kong, Ireland and Canada (8 each). Latin American countries do not have a good showing on this list, but are represented by Peru (2), Argentina (1), Brazil (1) and Chile (1).

Astonishingly (to us at least) Mexico does not get a single mention. Neither, it must be said, do Sweden or Norway.

The omission of Mexico from the list is significant, given that it is the world’s 11th largest country in terms of total population, 14th largest in area, is the 9th most attractive country for FDI, and has the 11th largest economy on the planet!

It is an especially puzzling omission, in a U.K. context, given that U.K. investment during the nineteenth century helped unlock the mineral riches of Mexico, finance its banks, build its railway network and so much more.

We invite UK geographers to purchase a copy of Geo-Mexico, the geography and dynamics of modern Mexicocome or hop on over to geo-mexico.com to find out what they’re missing.

Related posts: