Note: This is a copy of an article by an unknown author (publication date also unknown) as found originally at http://webspace.webring.com/people/hi/ilg21/puebla.htm and cached on waybackmachine.com:

Author’s Note: This article was drawn from a set of notes created during a trip to Mexico City, most of which were destroyed in a subsequent flood. Details on the Republican forces – and the Mexican’s movements during the battle – are drawn from Mexican books which are presumably accurate, but for which I cannot vouch. (This type of legendary event is prone to some distortion.) Information regarding the French forces is much easier to find. This article should be taken as a best effort to document the battle, according to what sources I could find. Comments and suggestions are welcome.

The most celebrated battle of the French invasion of Mexico occurred at the town of Puebla, on the road to Mexico City from the landing sites at Vera Cruz. The French, in the Convention of La Soledad, had agreed to withdraw to the coast before resuming hostilities, having moved their men inland under the Convention’s protection to avoid the diseases of the coastal areas. When negotiations between Mexico and France broke down, the French, with Mexican permission, left some sick soldiers in the healthier highlands, on the condition that no fit soldiers remained. When the Mexicans saw Frenchmen walking and carrying their small arms, after all the fit soldiers had ostensibly gone, they protested to the French commander, Lorencz. Lorencz overreacted, deciding that the complaint indicated the impending murder of his sick troops, despite the fact that the Mexicans were satisfied as to the status of the suspects.

The most celebrated battle of the French invasion of Mexico occurred at the town of Puebla, on the road to Mexico City from the landing sites at Vera Cruz. The French, in the Convention of La Soledad, had agreed to withdraw to the coast before resuming hostilities, having moved their men inland under the Convention’s protection to avoid the diseases of the coastal areas. When negotiations between Mexico and France broke down, the French, with Mexican permission, left some sick soldiers in the healthier highlands, on the condition that no fit soldiers remained. When the Mexicans saw Frenchmen walking and carrying their small arms, after all the fit soldiers had ostensibly gone, they protested to the French commander, Lorencz. Lorencz overreacted, deciding that the complaint indicated the impending murder of his sick troops, despite the fact that the Mexicans were satisfied as to the status of the suspects.

Consequently, the French did not complete their retreat to the coast, instead occupying Orizaba. This denied the Mexicans the ability to defend the passes between Orizaba and Vera Cruz. Zaragoza, the Mexican commander, fell back on his second line of defense, the steep pass of Aculzingo. Here, on April 28, the French and Mexicans fought a sharp engagement in which the Mexicans were easily beaten.

Zaragosa retreated to the fortified town of Puebla, which had been both defended and taken during the Wars of Reform (1857-1860), and was protected by five forts arranged on the hills outside the town. He had some 12,000 effectives in the Army of the East, not all of whom were deployed in the town. Lorencz’s Conservative Mexican advisers had fought at Puebla during the recent conflict, and advised him to attack it from the east, instead of the north, which was the French line of approach. Lorencz ignored the advice, advancing straight on the city. (He had heard that the population was friendly to the French, and was only kept in line by the Republican garrison. Thus, he thought a show of strength would cause the population to rise up, and the Republicans to crumble. This was to be proven badly wrong.) He established himself in the town of Amozoc on May 4.

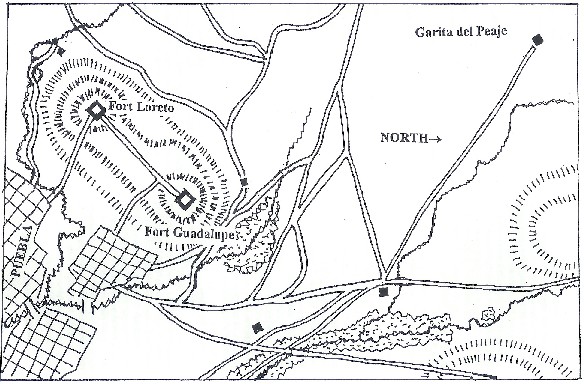

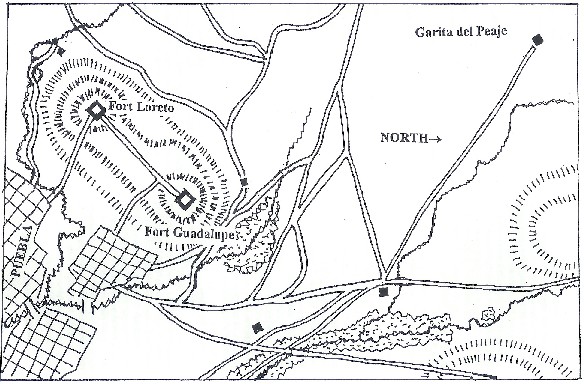

(The map here represents a 5′ x 9′ wargames table at approximately 1″ = 25 yards. Note that the arrow labelled “North” is actually pointing east!)

(The map here represents a 5′ x 9′ wargames table at approximately 1″ = 25 yards. Note that the arrow labelled “North” is actually pointing east!)

The French formed up at the Garita de Peaje early the next morning, after a brief skirmish with the Mexican cavalry and a reconnaissance of the area. The troops were drawn up in three columns: the first to attack Fort Guadalupe directly, was supported by the fire of the three batteries of French artillery, and contained the two battalions of the 2nd Zouaves. The second column, to the right of the first, contained only the Naval Infantry battalion. It was to act as a flank guard against mexican attacks from that quarter. The third column, consisting of only the 1st battalion of the 3rd Marine Fusiliers, was deployed to the left of the first column and assigned the role of supporting the attack on Guadalupe. The two battalions of the 99th Line infantry, the 2nd battalion of the Marine Fusiliers, the 1st Chasseurs a Pied, and the Chasseurs de Vincennes were held in reserve under the command of Colonel L’Heriller. The single squadron of Chasseurs d’Afrique was assigned to guard the flanks of the advance against the Mexican cavalry. A small party of engineers was assigned to each column.

To the north of Puebla, the forts of Loreto and Guadalupe crowned the tops of two heights, connected by a fortified road running just over the peak of the hill. Zaragoza drew up his army to the east of Fort Guadalupe (the easternmost of the two), facing north, so that he could maneuver to face an attack from north or east as necessary. He sent out a skirmisher screen, with his cavalry deployed all the way to his right (60 troopers were initially detached to observe the French), and the Zappadores were deployed on the slope between his left flank and the fort. The end of his infantry line (Diaz’ brigade)was deployed in a brickworks (“La Ladrillera”).

At 11:00 AM, the French bombarded Fort Guadalupe from a distance of about 2,500 yards, causing some damage and casualties. Lorencz advanced his batteries a few hundred yards and resumed the bombardment, this time to no effect. After an hour and a half of bombardment, with half his shells gone, he ordered his troops forward in an assault on the fort.

They were fired on by artillery from both forts, and came under a good deal of musketry; during the French approach, Zaragosa had countermarched the brigades of Lamadrid and Berriozabal and half of the cavalry under Alvarez to protected positions between the forts. The French advanced three times, each assault coming closer than the last. The reserves were slowly committed, until the entire French force was engaged. For the second assault, a double attack was made, not just on Fort Guadalupe, but also towards the town, on the east. This diversionary attack resulted in fierce hand-to-hand combat involving the Zappadores and some other Republican troops, and the Chasseurs de Vincennes, the squadron of Chasseurs d’Afrique, and the 1st battalion of the 99th Line. The Chasseurs a Pied and the zouaves made a final push on Fort Guadalupe, one soldier scaling the walls to plant the Tricolor there, but the man was killed and the flag torn down. The third assault found the French artillery out of ammunition, so the attacks were unsupported. At one point the Morelia battalion in Fort Guadalupe broke and fled, but Arriate rallied the men and they returned to their positions before the fort, defended only by the gunners, could be captured.

After the final assault was repulsed, Zaragoza ordered his cavalry on the right, under Felix Diaz, to charge the French; this worked admirably, accompanied by a simultaneous cavalry movement on the left. At the same time, the troops concealed along the road between the forts wheeled out toward the retreating French, pivoting on their right flank. The Chasseurs a Pied formed square to cover their army’s withdrawal from the Mexican cavalry.

At 3:00 PM it began to rain, the afternoon thunderstorm having been a daily occurrence for a week and more. The ground in front of the forts became very slippery, and at 4:00 PM Lorencz withdrew to positions further back from the town, to await the Mexican counter-attack. His casualties were 462 killed and 8 captured. The Mexicans lost 83 killed and 131 wounded, with 12 captured or missing.

Zaragoza, knowing both the political effects of the French repulse and the improbability of defeating the French in the open field, held his ground. After two days of waiting, Lorencz withdrew to Orizaba. News of the battle was received in France as a challenge to the national honor, and an additional 29,000 men (and a new overall commander – Forey) were sent to Mexico. The French later returned to besiege and take the town, but the victory in 1862 became the holiday we know – Cinco de Mayo – a symbol of the victory of the people over the agents of foreign imperialism.

Orders of Battle

French

- Major-General de Lorencz

- 1st Chasseurs a Pied – 1 battalion (720)

- Chasseurs de Vincennes – 1 battalion (700)*

- 99th Line Infantry – 2 battalions (1544)

- 2nd Zouaves – 2 battalions (1143)

- 2nd Squadron, 2nd Chasseurs d’Afrique (173)

- 2nd Marine (Colonial) Infantry Regt. – 2 battalions (1280)

- Naval Infantry – 1 battalion (480)

- 1st Battery, 9th Artillery Regt. (six 12#)

- 2nd Battery, Marine Artillery (six 4#)

- Marine Mountain Howitzer Battery (six 4#)

* This unit was a volunteer (foot) chasseur unit, mostly made up of veterans recently discharged from disbanded Chasseur a Pied battalions. It would be exactly like the regular chasseurs, and probably wore a similar uniform.

Notes: Numbers in parenthesis were French strengths at landing in Vera Cruz. Note that a portion of the French would have succumbed to illness (only 6,000 out of around 7,000 took the field). The strengths given here may thus be slightly high. French artillery was rifled muzzle-loaders. The French infantry all carried the Minie rifle, and the Chasseurs d’Afrique were equipped with the 1842 percussion musket (dragoon pattern). French infantry was generally quite good, especially the zouaves. Note that the Naval Infantry are in fact sailors, dressed much as they were during the defense of Paris in the Franco-Prussian War (although they may have worn the tropical white uniforms instead of blue). The Marine Infantry are not sailors, but marines, dressed in a fashion similar to the line infantry, but with dark blue (some sources say light blue-grey) trousers with a red stripe down the leg.

Republican Mexican

Army of the East: General Zaragoza

- Commander of the Interior Lines: General Miguel Negrete (in charge of forts Guadalupe and Loreto)

- Fort Loreto: General Rojo

“Reforma” battalion from Brigade of Morelia (600)

- Fort Guadalupe: General Arriata

One battalion from Brigade of Morelia (600)

- Reserve: Colonel Juan N. Mendez (300)

60th Battalion Nacional of Puebla, plus companies of Tetela, Xochapulco, Zacapoaxtla, and Apulco

Field Army

- Infantry Brigade: General Felipe Berriozabal (1082)

- 1st Battalion of Toluca

- 3rd Battalion of Toluca

- Fijo de Vera Cruz Battalion

- Infantry Brigade: Colonel Francisco LaMadrid (1020)

- Rifles of San Luis (initially deployed in front of the Mexican position as a skirmish line)

- Zapadores Battalion (Colonel Miguel Balcazar)

- Reforma Battalion of San Luis Potosí

- Infantry Brigade: General Porfirio Diaz (1000)

- Guerrero Battalion (Lt. Colonel Mariano Jimenez)

- Rifle Battalion

- Cavalry: General Antonio Alvarez (610)

- Provisional Regiment (under Alvarez’ command)

- Regt. Carabineros a Caballo, 2 squadrons (?)

- Regt. Lancers of Toluca, 2 squadrons

- Provisional Regiment: Lieutenant Felix Diaz (Porfirio’s brother)

- Trujano Squadron (Major Casimiro Ramirez)

- Regt. Lancers of Toluca, 1 squadron

- Regt. Lancers of Oaxaca, 2 squadrons (?)

“?” indicates uncertainty about how many squadrons were present

18 guns in three batteries, all smoothbore muzzle-loaders, probably 12#. One battery (“Vera Cruz”) is in Fort Guadalupe; one battery is in Fort Loreto, and one is deployed with P. Diaz’ brigade.

Notes: The Mexican infantry were equipped with smoothbore percussion muskets. The Zapadores battalion was one of the elite formations of the Republican army, designated an “engineer unit (and thus probably with black facings instead of thye infantry’s red or the rifles’ green), but fighting (I believe) as infantry in this battle. This army was made up of veterans from the Wars of Reform, and would possibly retain the older grey uniforms of that force. It should be noted that Mexican cavalry almost always carried the lance, despite designations, and would have smoothbore percussion carbines if any firearms were carried at all.

Notes on the Map: The rivers shown on the map are fordable at all points, although paintings of the period show them as flowing through ravines. The hills are gentle slopes, which the Mexicans advanced across in line formation at the end of the battle. The woods would be very light scrub brush, this basically being arid farmland. Two black rectangles toward the bottom of the map represent “La Ladrillera”, a brickworks, just south of Fort Guadalupe, and the “Garita de Amozoc”, a train station, further east. The town of Puebla, while walled, was open in the areas shown on this map, if period paintings can be believed.