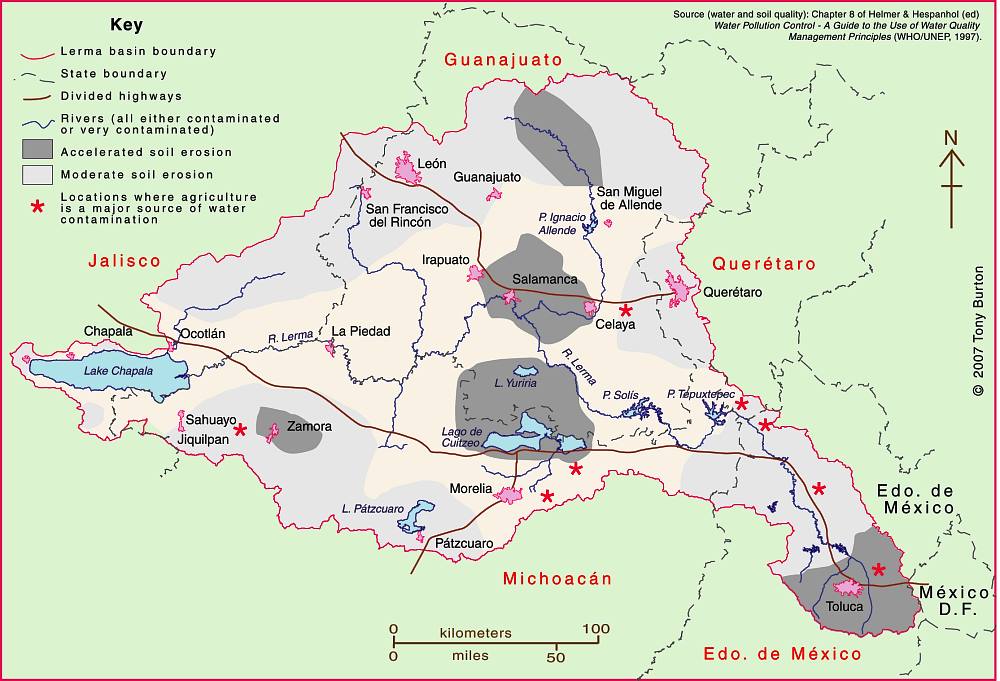

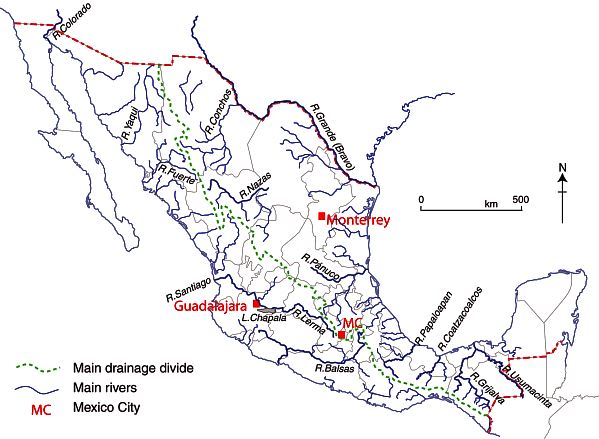

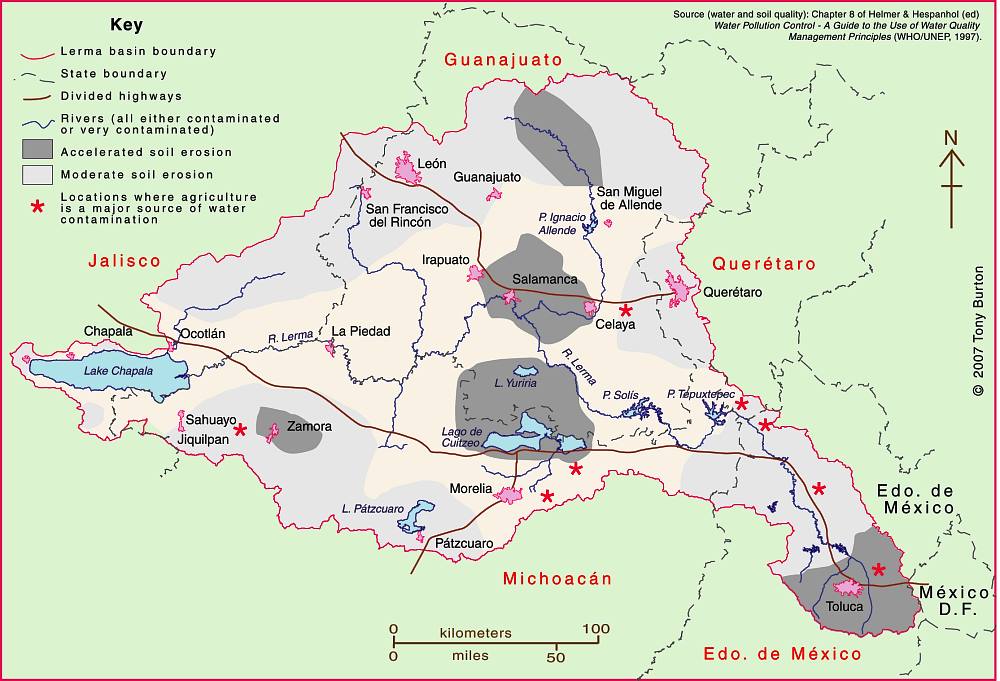

The Lerma-Chapala Basin (see map) is one of Mexico’s major river systems, comprising portions of 127 municipalities in five states: México, Querétaro, Michoacán, Guanajuato and Jalisco.

The basin has considerable economic importance. It occupies only 2.9% of Mexico’s total landmass, but is home to 9.3% of Mexico’s total population, and its economic activities account for 11.5% of national GDP. The basin’s GDP (about 80 billion dollars/year) is higher than the GDP of many countries, including Guatemala, Costa Rica, Honduras, Paraguay, Bolivia, Uruguay, Croatia, Jordan, North Korea and Slovenia.

The Lerma-Chapala Basin. Click map to enlarge. Credit: Tony Burton / Geo-Mexico

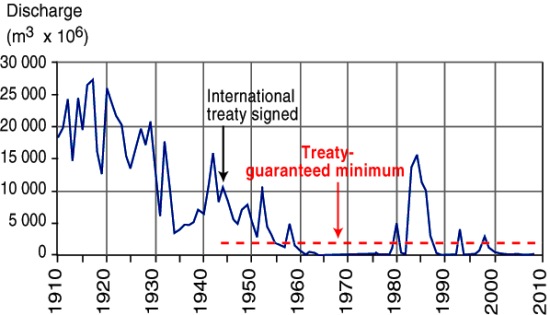

Given this level of economic activity, it is probably not surprising that the pressures on natural resources in the basin, especially water, are enormous. Historically, the downstream consequence of the Lerma Basin’s agricultural and industrial success has been an inadequate supply of (heavily polluted) water to Lake Chapala.

Following decades of political inactivity or ineffectiveness in managing the basin’s water resources, solid progress finally appears to have been made. Part of the problem previously was a distinct lack of hard information about this region at the river basin scale. The statistics for such key elements as water usage, number of wells, replenishment rates, etc. were all (to put it politely) contested.

Fortunately, several scientific publications in recent years have redressed the balance, and the Lerma-Chapala Basin is now probably the best documented river basin in Mexico. This has allowed state and federal governments to negotiate a series of management agreements that are showing some positive signs of success.

The first of these key publications was “The Lerma-Chapala Watershed: Evaluation and Management“, edited by Anne M. Hansen and Manfred van Afferden (Klewer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2001). This collection of articles featured contributions from researchers in several universities and research centers, including the University of Guadalajara, Mexican Institute of Water Technology, Autonomous University of Guadalajara, Baylor University, the Harvard School of Public Health and Environment Canada. Click here for my comprehensive description and review of this volume on MexConnect.com.

Perhaps the single most important publication was the Atlas de la cuenca Lerma-Chapala, construyendo una visión conjunta in 2006. Cotler Ávalos, Helena; Marisa Mazari Hiriart y José de Anda Sánchez (eds.), SEMARNATINE-UNAM-IE, México, 2006, 196 pages. (The link is to a low-resolution pdf of the entire atlas). The atlas’s 196 pages showcase specially-commissioned maps of climate, soils, vegetation, land use, urban growth, water quality, and a myriad of other topics.

More recently, a Case Study of the Lerma-Chapala river basin: : A fruitful sustainable water management experience was prepared in 2012 for the 4th UN World Water Development Report “Managing water under uncertainty and risk”. This detailed case study should prove to be especially useful in high school and university classes.

The Case Study provides a solid background to the Lerma-Chapala basin, including development indicators, followed by a history of attempts to provide a structural framework for its management.

In the words of its authors, “The Lerma Chapala Case Study is a story of how the rapid economic and demographic growth of post-Second World War Mexico, a period known as the “Mexican Miracle”, turned into a shambles when water resources and sustainable balances were lost, leading to pressure on water resources and their management, including water allocation conflicts and social turbulence.”

On a positive note, the study describes how meticulous study of the main interactions between water and other key development elements such as economic activity and social structures, enabled a thorough assessment on how to drive change in a manner largely accepted by the key stakeholders.

The early results are “stimulating”. “Drawbacks and obstacles are formidable. The main yields are water treatment and allocation, finances, public awareness, participation and involvement. The main obstacles are centralization, turbid interests, weak capacity building, fragile water knowledge; continuity; financial constraints; and weak planning.”

Sustainable water usage is still a long way off. As the Case Study cautions, “There is still much to do, considering the system Lerma-Chapala responds directly to a hydrologic system where joint action and especially abundant involvement of informed users is required, to achieve sustainable use of water resource.”

One minor caveat is that the Case Study does not offer full bibliographic reference for all of the maps it uses, which include several from the previously-described Atlas de la cuenca Lerma-Chapala, construyendo una visión conjunta.

Related posts: