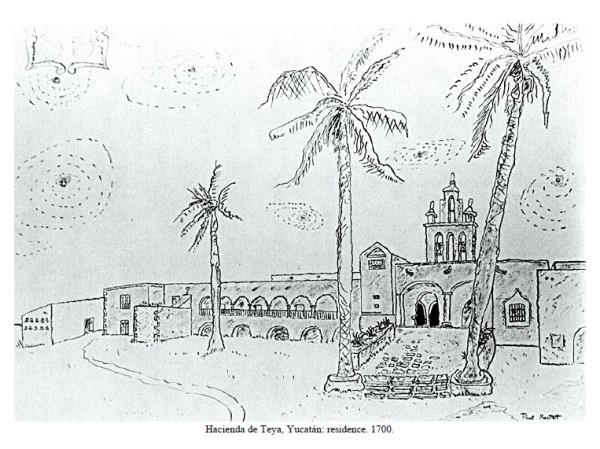

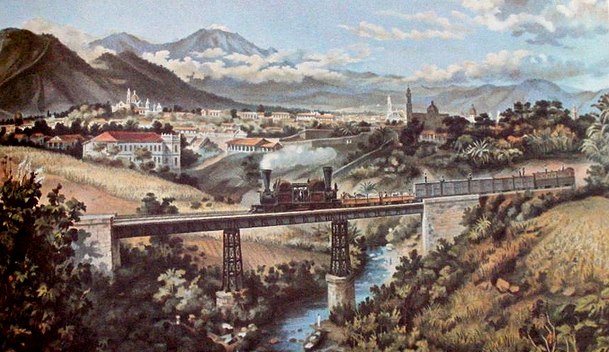

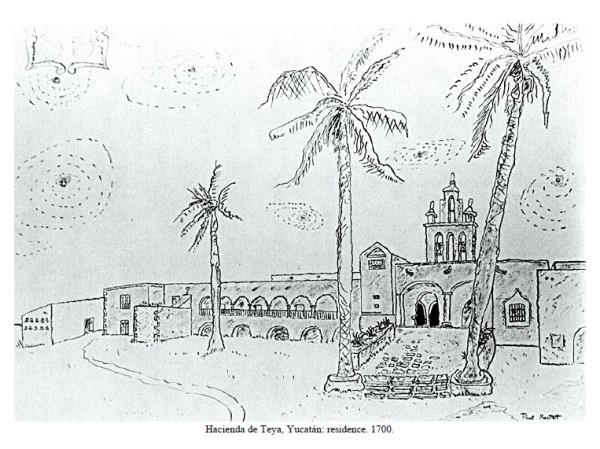

The Haciendas of Mexico: An Artist’s Record, by Paul Alexander Bartlett, first published in 1990 and now available as a free Gutenburg pdf or Epub, is a great starting point for anyone interested in the history, economics, art and architecture of the hundreds of colonial haciendas which still grace Mexico’s rural areas. Bartlett made one of the earliest artistic records of more than 350 of these haciendas, dragging his family around the country for years as he obsessively explored lesser-known places. The photographs and pen and ink illustrations in his outstanding book were made on site from 1943 to 1985.

Geo-Mexico is reader-supported. Purchases made via links on our site may, at no cost to you, earn us an affiliate commission.

Learn more.

Pen-and-ink drawing of Hacienda de Teya, Yucatán, by Paul Bartlett.

Bartlett’s hacienda art work has been displayed at the Los Angeles County Museum, the New York City Public Library, the University of Virginia, the University of Texas, the Instituto Mexicano-Norteamericano in Mexico City, and at the Bancroft Library, among other places.

Paul Alexander Bartlett (1909-1990) attended Oberlin College and the University of Arizona, before studying art at the National University of Mexico (UNAM) and in Guadalajara. He was an instructor in creative writing at Georgia State College, Editor of Publications at the University of California Santa Barbara (1964-70) and wrote dozens of short stories and poems. His books include the short novel Adios, mi México (1983), and the novel When the Owl Cries (1960).

Writing must run in the family. Bartlett’s wife was the well-known poet and writer Elizabeth Bartlett (1911-1994). The couple met in Guadalajara in 1941 and married two years later in Sayula. Their son Steven James Bartlett is a widely published author in the fields of psychology and philosophy.

In the foreward to The Haciendas of Mexico: An Artist’s Record, novelist James Michener writes that:

I first became aware of the high artistic merit of Paul Bartlett’s work on the classic haciendas of Old Mexico when I came upon an exhibition in Texas in 1968. His drawings, sketches, and photographs evoked so effectively the historic buildings I had known when working in Mexico that I wrote to the architect-artist to inform him of my pleasure.”

Gisela von Wobeser observes, in her introduction, that,

When Bartlett began his hacienda visits in the 1940s, he found many of the hacienda buildings in ruins, exposed to the ravages of time and vandalism. Buildings had been converted into chicken coops, pigsties, public apartments, and machine shops. Others served as sources for construction materials, from which were scavenged rocks, bricks, beams, and tiles for the habitations of the local population. In some cases the destruction was total: All the hacienda’s structures were removed, and only the name of the place alluded to the fact that a hacienda had ever existed there.

At other haciendas, buildings were adapted to new uses. They were transformed into hotels, resorts, government buildings, barracks, hospitals, restaurants, and schools. The exterior of the buildings were generally left intact; interiors were completely changed.

The best—preserved hacienda buildings were those that continued to function as country properties or vacation homes. In these, Bartlett often found furnishings and utensils from the epoch of Don Porfirio, surrounded by the old traditions of Mexican country life.”

von Wobeser makes the useful distinction between three types of hacienda: those where grains were the main output, those specializing in cattle-rearing, and those for sugar-cane cultivation and processing.

The book describes haciendas in almost every state of the Republic. A handy map and list are provided of which haciendas are located in each state. There are more than 100 pen-and-ink illustrations and photographs in total in the book, which is arranged in seven chapters:

- The Hacienda System

- Through the Eyes of Hacienda Visitors

- Hacienda Life

- Fiestas

- Education

- The Revolution

- Mexico Since the Revolution

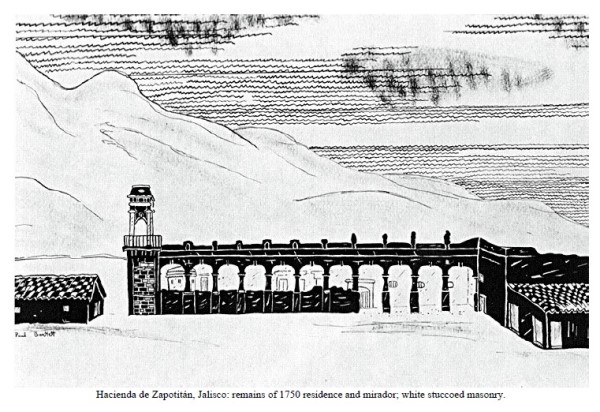

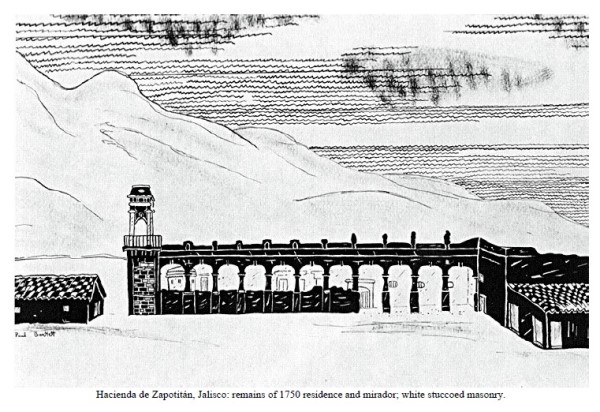

The accompanying text, written from a non-specialist perspective, is always lively, informative and interesting. The style of illustrations is varied, in keeping with the immense variety of haciendas that the author explored and sketched.

Pen-and-ink drawing by Paul Bartlett of Hacienda de Zapotitán, Jalisco

Coincidentally, the hacienda of Zapotitán in Jalisco (see illustration above), located close to Jocotepec and Lake Chapala, is the first hacienda to be featured in the on-going series of articles by modern-day hacienda explorer Jim Cook. Jim spends countless hours researching old haciendas, and regularly goes exploring with friends to see what is left on the ground today. His descriptions and photographs are easily the best contemporary accounts of the haciendas in western Mexico.

All in all, this is a really useful addition to the literature about Mexico’s haciendas, one guaranteed to answer many of the questions and doubts that visitors to Mexico often express about just how haciendas functioned and what working and living conditions were like, both for the owner’s family and the workers.

An archive of Bartlett’s original pen-and-ink illustrations and several hundred photographs is held in the Benson Latin American Collection of the University of Texas in Austin. A second collection of hacienda photographs and other materials is maintained by the Western History Research Center of the University of Wyoming in Laramie.

Want to visit some haciendas?

Chapter 9 of my Western Mexico, A Traveler’s Treasury (2013) focuses on the “Hacienda Route” to the south and west of Guadalajara, with an itinerary that includes visiting several haciendas within easy reach of the city.

Related posts: