In 2005, a geography research project known as México Indígena, based at the University of Kansas, received 500,000 dollars in funding from the US Defence Department to map indigenous villages in two remote parts of Mexico, in collaboration with the Autonomous University of San Luis Potosí , Radiance Technologies (USA), SEMARNAT (Mexico’s federal environmental secretariat) and partnered with the US Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO).

Under some circumstances, this might not be a huge problem. After all, the large-scale survey maps of many countries were developed primarily by military engineers with military funding, in the interests of national security. In the past, several countries, including France and the UK, extended their map-making to cover their colonies or dependent territories.

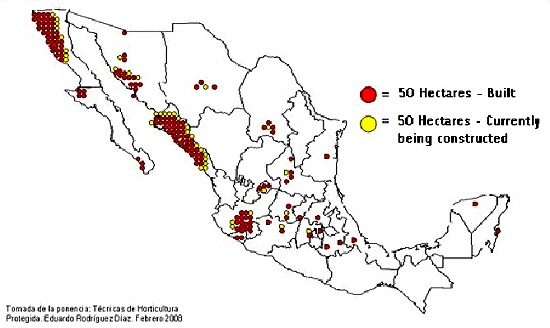

What sets México Indígena apart is that, between 2005 and 2008, under the guise of “community participatory mapping”, US researchers, funded by the US military, collected detailed topographic, economic and land tenure information for several villages in Mexico, an autonomous nation, whose people have long viewed their northern neighbors with considerable suspicion. After all, in the mid-19th century, the USA gained a large portion of Mexico’s territory.

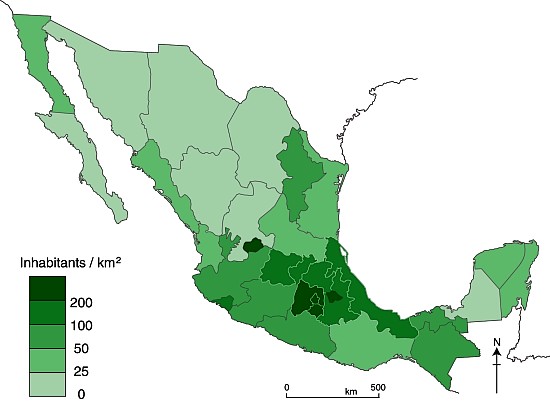

The indigenous villages mapped were in the Huasteca region of San Luis Potosí, and in the Zapotec highlands of Oaxaca, the most culturally diverse state in Mexico. The villages mapped in Oaxaca included San Juan Yagila and San Miguel Tiltepec.

México Indígena is part of a larger mapping project, the Bowman Expeditions. In the words of the México Indígena website:

“The First Bowman Expedition of the American Geographical Society (AGS) was developed in Mexico… The AGS Bowman Expeditions Program is based on the belief that geographical understanding is essential for maintaining peace, resolving conflicts, and providing humanitarian assistance worldwide.”

“The prototype project in Mexico is producing a multi-scale GIS database and digital regional geography, using participatory research mapping (PRM) and GIS, aiming at developing a digital regional geography, or so-called “digital human terrain,” of indigenous peoples of the country.”

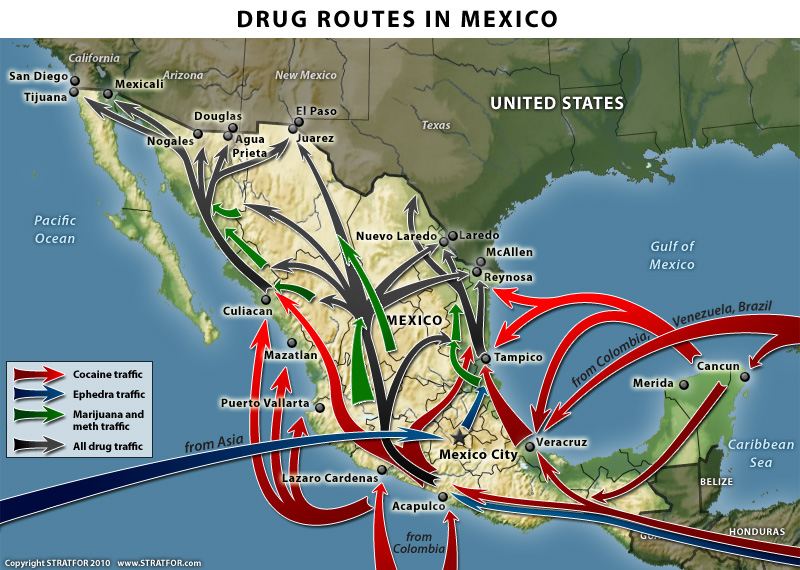

Mexico’s indigenous communities are the poorest in the country, beset by poverty, poor access to education and health care, and limited economic opportunities. Among the common concerns voiced by protesters against the mapping project were that the information collected could be used for:

- Counter-insurgency operations

- Identification and subsequent acquisition of resources

- Biopiracy

Despite attempts at clarification by the project leaders, some communities remain upset, claiming that they were not made aware of the US military’s funding, and have demanded that all research findings either be returned to the community or destroyed (see, for example, this open letter from community leaders in San Miguel Tiltepec).

Choose the conclusion you prefer:

1. Mexico’s indigenous peoples face enough challenges already. Their best way forward is if US military funding for mapping beats a hasty retreat, or

2. Mexico’s indigenous peoples face enough challenges already. Their best way forward is to welcome and embrace offers of help from outside their community.

Further reading/viewing:

- Wikipedia entry about the México Indígena controversy

- México Indígena – project website hosted by the University of Kansas

- US military-funded mapping project in Oaxaca, article by Cyril Mychalejko (overview of controversy)

- Threat of Genocide: US Military Mapping Against Mexico’s Indigenous by Simon Sedillo (an anti-project account)

The México Indígena controversy is the subject of a short film entitled, “The Demarest Factor: US Military Mapping of Indigenous Communities in Oaxaca, Mexico”. The film investigates the role of Lt. Col. Geoffrey B. Demarest ( a US Army School of the America’s graduate) and the true nature of the mapping project. It discusses parallels between US political and economic interests within the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and a US military strategy designed to secure those very interests.

Things to think about:

- Should academic research in foreign countries ever be funded from military sources?

- Does the right of self-determination mean that indigenous peoples can refuse to cooperate with academic researchers, even when the research may bring benefits to the community?

- Should researchers ever be allowed to collect information from a community without the community’s express consent?

The irony about the choice of “Bowman” for the AGS research expeditions.

Isaiah Bowman (1878-1950), born in Canada, was a US geographer who taught at Yale from 1905 to 1915. He became Director of the AGS in 1916, a position he only relinquished when appointed president of Johns Hopkins University in 1935. He served as President Woodrow Wilson’s chief territorial adviser at the Versailles conference in 1919. Bowman’s best known work is “The New World: Problems in Political Geography” (1921). His career has been subject to considerable scrutiny by a number of geographers including Geoffrey Martin (The life and thought of Isaiah Bowman, published in 1980) and Neil Smith who, in American Empire: Roosevelt’s Geographer and the Prelude to Globalization (2003) labels Bowman an imperialist, precisely the claim made by many of its opponents about the México Indígena mapping project.