Somewhat surprisingly, the number of Mexicans speaking indigenous languages has increased significantly in the past 20 years. In 2010 there were 6.7 million indigenous speakers over age five compared to 6.0 million in 2000 and 5.3 million in 1990.

There are two factors contributing to this finding:

- First, indigenous speakers are teaching their children to speak their indigenous language.

- Second, indigenous speakers have higher than average birth rates.

The number of indigenous speakers that cannot speak Spanish decreased slightly from 1.0 million in 2000 to 981,000 in 2010.

The most widely spoken indigenous languages are:

- Nahuatl, with 1,587,884 million speakers, followed by

- Maya (796,405),

- Mixteca (494,454),

- Tzeltal (474,298).

- Zapotec (460,683), and

- Tzotzil (429,168).

[Note: language names used here include all minor variants of the particular language]

About 62% of all indigenous language speakers live in rural areas, communities with under 2,500 inhabitants. Nearly 20% live in small towns between 2,500 and 15,000, while about 7% in larger towns, and 11% live in cities of over 100,000 population. Indigenous speaking areas tent to have low levels of development. Over 73% of the population In Mexico’s 125 least developed municipalities speak an indigenous language.

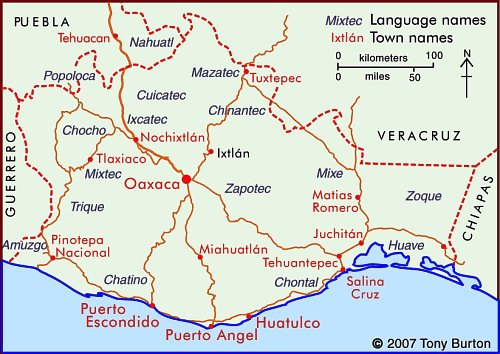

States with the most indigenous speakers tend to be in the south. In Oaxaca, almost 34% of the population over age three speak an indigenous language followed by Yucatán (30%), Chiapas (27%), Quintana Roo (16%) and Guerrero and Hidalgo (15%). States with the fewest indigenous speakers are Aguascalientes and Coahuila (0.2%), Guanajuato 90.53%) and Zacatecas (0.4%).

A total of 15.7 million Mexicans over age three consider themselves indigenous. Surprisingly, 9.1 million of these cannot speak any indigenous language. There are 400,000 Mexicans who can speak an indigenous language, but do not consider themselves indigenous.

Related posts:

- Oaxaca is the most culturally diverse state in Mexico

- An overview of Mexico’s indigenous peoples

- The geography of languages in Mexico: Spanish and 62 indigenous languages

- Mexico’s indigenous place names

Chapter 10 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico is devoted to Mexico’s indigenous peoples. Many other chapters of Geo-Mexico include significant discussion of the cultural and development issues facing Mexico’s indigenous groups.

From 1950-1970, the Mexican government opted for a modernization approach, building roads (including the Pan-American highway) and attempting to upgrade agricultural techniques. The mainstay of the regional economy is coffee. During this period, most Mam were peasant farmers, subsisting on corn and potatoes, gaining a meager income by working, at least seasonally, on coffee plantations. Working conditions were deplorable, likened in one report to “concentration camps”. Plantation owners forced many into indebtedness. The Mam refer to this period as the time of the “purple disease”:

From 1950-1970, the Mexican government opted for a modernization approach, building roads (including the Pan-American highway) and attempting to upgrade agricultural techniques. The mainstay of the regional economy is coffee. During this period, most Mam were peasant farmers, subsisting on corn and potatoes, gaining a meager income by working, at least seasonally, on coffee plantations. Working conditions were deplorable, likened in one report to “concentration camps”. Plantation owners forced many into indebtedness. The Mam refer to this period as the time of the “purple disease”: