Proficiency in English is widely seen as an ever-more-essential skill in our increasingly-internationalized and business-oriented world. Many Mexicans have acquired excellent English, whether from education, family connections or residence abroad. It therefore comes as something of a shock to study the latest English Proficiency Index, put out by the Toronto-based organization, Education First (EF).

Education First modestly describes itself as “The World Leader in International Education”. (This claim is rather grandiose, given that the International Baccalaureate, for one, is far larger and much better known in educational circles worldwide).

The 2015 edition of EF’s English Proficiency Index (EPI) “ranks 70 countries and territories based on test data from more than 910,000 adults who took our online English tests in 2014. This edition continues to track the evolution of English proficiency, looking back over the past eight years of EF EPI data.”

EF categorizes the level of English proficiency in different places as “very high”, “high”, “moderate”, “low” or “very low”.

English proficiency in Mexico (grey = moderate; yellow = low; orange = very low). Credit: EF EPI, 2015

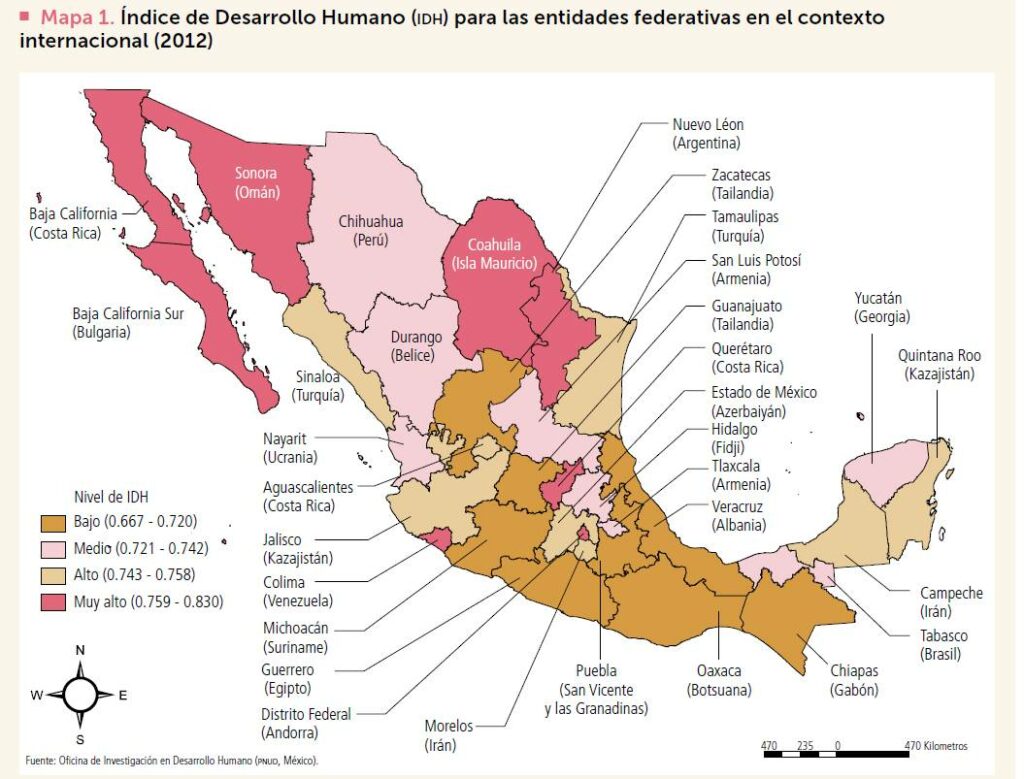

Strangely, Mexico does not do well on this index. According to EF, no state or city in Mexico performs beyond the “moderate” level (colored grey on the map). From the map, it appears that there is, in this context as in many others, something of a north-south divide in Mexico, with southern states under-performing in comparison with northern states.

The highest-scoring cities for English proficiency are Monterrey (53.59) and Mexico City (53.03), both classed as “moderate”, followed by Hermosillo (52.36), Tijuana (51.27), Guadalajara (50.52), Ciudad Juárez (49.35), and Mexicali (48.51), all classed as “low”. At the bottom end of proficiency, Puebla (47.84), Cancún (47.14), and Oaxaca (44.61) are all in the “very low” category.

EF recognizes that the people taking its tests are “self-selected and not guaranteed to be representative of the country as a whole. Only those people either wanting to learn English or curious about their English skills will participate in one of these tests. This could skew scores lower or higher than those of the general population.” On the other hand, it also claims that, “The EF English Proficiency Index is increasingly cited as an authoritative data source by journalists, educators, elected officials, and business leaders.”

That may be so, but given the EPI methodology and EF’s overblown claims of being “The World Leader in International Education”, perhaps we should take these results with a grain of salt ~ of which Mexico has lots!

Related posts:

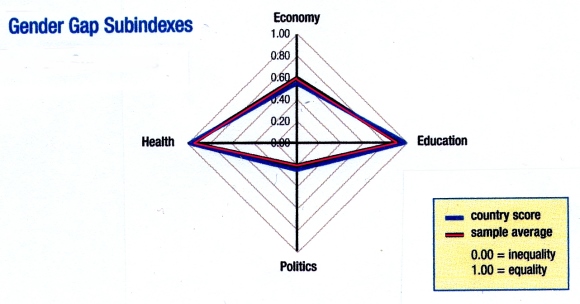

- The Gender Gap in Mexico in 2012 (Nov 2012)

- The rapid expansion of literacy and education in Mexico (Nov 2011)

- Are Mexican females overtaking males in literacy? (May 2011)

- 2010 Census data show a significant improvement in Mexican education (Apr 2011)

- How do Mexican students compare to those in other countries? (Jan 2013)