According to consumer surveys, only one out of every five Mexican households decorates a natural Christmas tree during the holiday season; the other 80% of households decorate artificial trees. About 75% of natural trees are bought from traditional retailers, with the remaining 25% purchased from informal street vendors. Almost all purchases of natural Christmas trees are made between 10 December and 25 December.

As of mid-December 2014, sales of trees are reported to be down on previous years. Retailers claim that the prices for imported trees (ranging from 330 pesos (about 25 dollars) for a 1-meter-high tree to 1,500 pesos (110 dollars) for a large tree) have led to greatly diminished demand. Prices for domestically grown trees range from about 100 to 1,000 pesos.

The total annual demand for natural Christmas trees is about 1.8 million. Mexico currently imports about 1 million trees a year, almost all from the USA and Canada. Annual imports are worth about $12 million. Imports are governed by strict standards, last revised in 2010, to ensure that no unwanted pests or diseases are brought into the country.

As of mid-December, at least 5500 trees had failed the health inspection at the border and had been returned to the USA. Officials from Mexico’s Federal Environmental Protection Agency (Procuraduría Federal de Protección al Ambiente, Profepa) identified several problems in shipments of Douglas Fir and Noble Fir trees. At Tijuana, one shipment of Douglas Fir was found to be infected a resin moth (Synanthedon sp.), and one with flatheaded fir borer (Buprestidae). In Mexicali, a shipment of Douglas Fir was infested with the Douglas-fir Twig Weevil (Cylindrocopturus furnissi), while in Nogales, imported trees were found to be accompanied by unwanted European Paper Wasps (Polistes dominula). None of these pests are normally found in Mexico.

Mexicali is the busiest border crossing in terms of Christmas tree imports, accounting for 35% of the total, followed by Tijuana (25%), Nogales (16%), Colombia (15%), Nuevo Laredo (4%), San Luis Río Colorado (3%), Reynosa (1%) and Puente Zaragoza-Isleta (in Chihuahua) (0.4%).

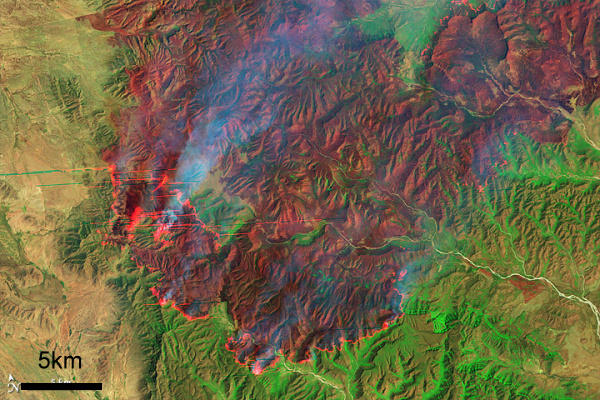

In the 1970s and 1980s, most natural Christmas trees sold in Mexico came from Mexico’s natural forests. Beginning in the 1990s, specialist Christmas tree nurseries and plantations were started.

According to the National Forestry Commission (CONAFOR), Mexico has almost 17,000 hectares of land planted in Christmas trees. The area of Christmas trees has increased very rapidly in recent years. This year, CONAFOR has provided some degree of financial assistance to farmers with 4,551 hectares of tree plantations in 18 states.

The main areas of Christmas tree plantations are in the interior highlands in the states of Mexico, Veracruz, Nuevo León, Mexico D.F., Puebla, Michoacán, Durango, Coahuila and Guanajuato. These states share temperate climate conditions and are close to the main markets in major cities.

The most common species grown in Mexico are Mexican White Pine (Spanish: Pino ayacahuite), Douglas Fir (Abeto douglas), Mexican Pinyon (Pino piñonero), Sacred Fir (Oyamel) and Aleppo Pine (Pino alepo).

Trees are harvested at between five and ten years of age. Mature plantations of Christmas trees can generate revenue of between 300,000 pesos and 500,000 pesos ($23,000-$38,000) for each hectare. This means that Christmas tree farming has become a profitable form of sustainable development in some rural communities, offering greater profit potential than using the same land to grow traditional rain-fed crops.

The planting of Christmas trees is supported by CONAFOR’s ProArbol program, which offers landowners incentives to conserve, restore, and sustainably exploit forest resources. CONAFOR claims this helps to limit urban sprawl, and counteract forest clearance for arable land, as well as to increase the capture and storage of carbon, thereby mitigating climate change. In addition, conifer plantations generate rural employment, reducing the effects of one of the key “push” factors behind rural-urban migration.

Note: This is an updated version of a post that was first published in 2012.

Main source:

USDA Foreign Agricultural Service GAIN report: Mexico: Christmas Trees, by Dulce Flores, Vanessa Salcido, and Adam Branson. 12 May 2011.

Related posts: