I love gifts, especially books, and especially when they are related to the geography of Mexico!

So, it was a doubly pleasant surprise recently to receive a copy of Glifos de la ciudad de México by Pablo Moctezuma Barragán (Gobierno del Distrito Federal, 2006; 103 pp.)

The author is an accomplished researcher, historian and politician who holds a teaching position at the Azcapotzalco campus of the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, and who spearheaded a campaign in Mexico City to bring the meanings of place names to life.

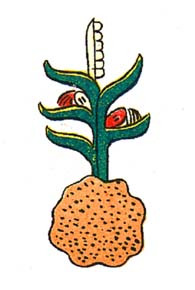

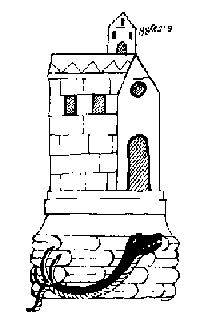

The project involved the installation around the city in 2006 of more than 300 works of art, all using traditional Talavera tiles, depicting pre-Hispanic glyphs, together with a brief explanation of their derivation and meaning. Each mosaic of 25 tiles measures one meter by one meter. The vast majority of the glyphs are depicted as they are known in ancient codices or other historic sources, but in a few cases, glyphs have been specially created, faithfully reflecting the ancient principles. Glifos de la Ciudad de México is a handy pocket guide to these glyphs.

The obligatory introductory statements by politicians are mercifully brief, though significantly for us, they do refer to the fact that many names depend on a circunstancia geográfica (a geographical circumstance) or are related to activities undertaken by the early settlers or to characteristic plants or animals. How encouraging to see such a tribute to geography!

Next comes a very interesting essay by Pablo Moctezuma Barragán, setting the scene for the full color illustrations of hundreds of glyphs which follow. The author discusses the origins of place name glyphs (the oldest date back 2500 years), and emphasizes that many reflect the importance of local geographic conditions. The forces of globalization may be at work in what is arguably the world’s largest city, but “It is important to rescue our roots”, argues Moctezuma Barragán, “We should not live like foreigners in our own land”.

He goes on to summarize the Nahuatl roots of many of the names and gives a potted history of the development of Mexico City.

Tile mosaic depicting glyph of Texcoco ("in the place where plants grow on rocks") on a wall in Mexico City. Credit: Glifos de la ciudad de México.

All the glyphs refer to names used somewhere in the city and many photographs show the commemorative tiled versions in situ in the city. In all, 322 glyphs were installed, and more than 220 of them are included in this book.

This is but one example of the many projects undertaken by Mexico City authorities in recent years to beautify the city.

What a neat idea, to introduce people, even as they go about their daily lives, to pre-Hispanic symbolism as it relates to local place names. These tiled works of art are a great way to encourage a sense of place and identity. They are not only beautiful, they serve to foment local pride. Geography is alive and well in Mexico City!

Related website.

Several hundred ancient glyphs, from Antonio Peñafiel’s 1885 “Nombres Geográficos de México,” can be viewed online as part of the Aztec Place Name Glyphs Project of the Department of Geography at the University of California, Berkeley.

Previous posts about Mexico’s place names:

- Many Mexican place names were changed following Mexican Independence (1821)

- The Spanish arrive and change lots of place names

- Mexican place names often have their roots in pre-Hispanic languages and have multiple levels of meaning

- How Mexico’s fourth highest peak got its name

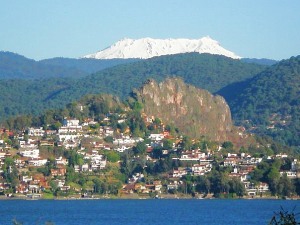

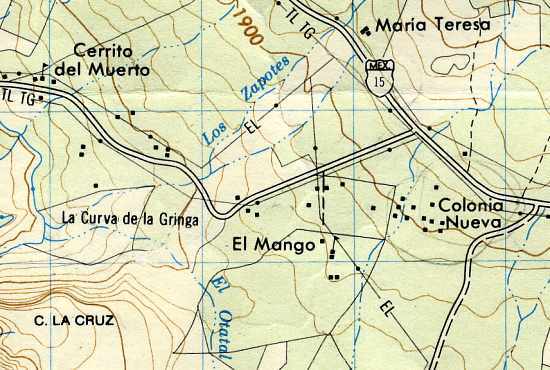

- “La Curva de la Gringa”, the American woman’s curve, a place name in Michoacán, Mexico

- Unusual place names in Mexico

- Mexico’s Spanish language place names

- Mexico’s indigenous place names