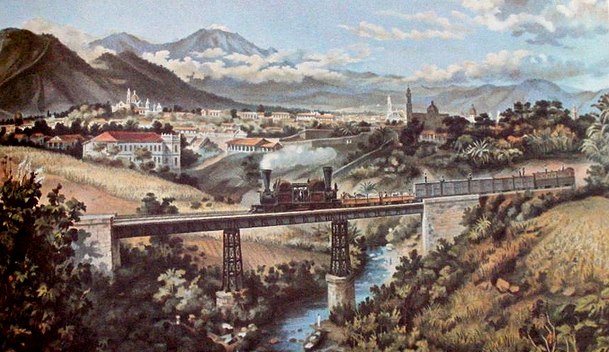

Early concessions (the first was in 1837) came to nothing. By 1860 Mexico had less than 250 km of short disconnected railroad lines and was falling way behind its northern neighbor, the USA, which already had almost 50,000 km. Political, administrative and financial issues, coupled with Mexico’s rugged topography, also prevented Mexico from keeping up with other Latin American nations. Mexico City was finally linked by rail to Puebla in 1866 and Veracruz in 1873.

In deciding the best route for the Veracruz-Mexico City line, Arthur Wellington, an American engineer, developed the concepts which later became known as positive and negative deviation. At first glance, it might be assumed that the optimum route for a railway is the shortest distance between points, provided that the maximum possible grade is never exceeded. Negative deviations lengthen this minimum distance in order to avoid obstacles such as the volcanic mountains east of Mexico City: the Veracruz line skirts the twin volcanic peaks of Popocatepetl and Ixtaccihuatl before entering Mexico City from the north-east. Positive deviations lengthen the minimum distance in order to gain more traffic.

At the end of the nineteenth century, during the successive presidencies of Porfirio Díaz, railway building leapt forward. Díaz aggressively encouraged rail development through generous concessions and government subsidies to foreign investors. By 1884 Mexico had 12,000 km of track, including a US-financed link from Mexico City to the USA through Torreón, Chihuahua and Ciudad Juárez. A British company had completed lines from Mexico City to Guadalajara, and from Mexico City via Monterrey to Nuevo Laredo.

Different gauge tracks typified a system based on numerous concessions but no overall national plan. By the turn of the century, additional tracks connected Guadalajara, San Luis Potosí and Monterrey to the Gulf coast port of Tampico. A line connecting the Pacific and Gulf coasts was also completed. Durango was now connected to Eagle Pass on the US border. A second line to Veracruz was constructed, with a spur to Oaxaca. Laws passed in 1898 sought to bring order to the rapid and chaotic expansion of Mexico’s rail system. Foreign concessions were restricted. Subsidies were only made available for the completion of missing links such as lines to Manzanillo and the Guatemala border. Efforts were made to standardize track gauges.

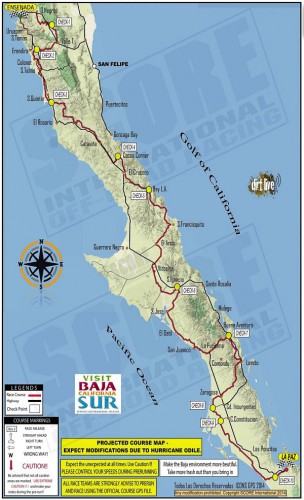

However, the country’s 24,000 km railroad network still had serious deficiencies. There were only three effective connections from the central plateau to the coasts. There were no links from central Mexico to either the Yucatán Peninsula or to the northwestern states of Nayarit, Sinaloa, Sonora and Baja California. The only efficient way to move inland freight from Chihuahua, Torreón, Durango or Ciudad Juárez to the Pacific was either north through the USA or all the way south and through Guadalajara to Manzanillo. The Sonora railroad linked Guaymas and Hermosillo to the USA, but not to the rest of Mexico.

Despite their weaknesses, railroads revolutionized Mexico. The railroads had average speeds of about 40 kph (25 mph) and ran through the night. They were five to ten times faster than pre-railroad transport. They lowered freight costs by roughly 80%. They shrank the size of Mexico in terms of travel time by a factor of between five and ten. They were also much cheaper and far more comfortable than stagecoaches. The estimated savings from railroad services in 1910 amounted to over 10% of the country’s gross national product. Between 1890 and 1910, the construction and use of railroads accounted for an estimated half of the growth in Mexico’s income per person. In addition, the railroads carried mail, greatly reducing the time needed for this form of communication. Clearly, the benefits of railroads far outweighed their costs.

Foreign companies gained mightily from their investments building railroads, which were almost entirely dependent on imported locomotives, rolling stock, technical expertise, and even fuel. But Mexicans also benefited enormously; in the early 1900s over half of the rail cargo supplied local markets and industries. The railroads thrust much of Mexico into the 20th century.

Cities with favorable rail connections grew significantly during the railroad era while those poorly served were at a severe disadvantage. The speed and economies of scale of shipping by rail encouraged mass production for national markets. For example, cotton growing expanded rapidly on irrigated farms near Torreón because the crop could be shipped easily and cheaply to large textile factories in Guadalajara, Puebla and Orizaba. Manufactured textiles were then distributed cheaply by rail to national markets. Elsewhere, the railroads enabled large iron and steel, chemical, cement, paper, shoe, beer and cigarette factories to supply the national market.

On the other hand, most Mexicans still lived far from railroad lines and relied on foot or mule transport while practicing subsistence agriculture. In addition, the cost of rail tickets was prohibitively expensive for many Mexicans; paying for a 70 km (43 mi) trip required a week’s pay for those on the minimum wage. The railroads greatly expanded the gap between the ‘have’ and the ‘have not’ areas of the country. Almost all the Pacific coast and most of southern Mexico did not benefit from the railroads. Such growing inequalities contributed to the Mexican Revolution.

After the Revolution, network improvements were hindered by poor administration, corruption, labor unions and a shift of government priority to roads. The west coast railroad from Sonora to Guadalajara was completed in 1927. The Yucatán Peninsula was joined to the national network in the 1950s and the famous Chihuahua to Los Mochis line through the Copper Canyon was completed in 1961, finally linking Texas and Mexico’s northern plateau to the Pacific Ocean.

In the second half of the 20th century, the rapidly improving road network and competition from private autos, buses and, later, airplanes caused railroad traffic to decline significantly. Freight traffic on the nationalized railroad maintained a competitive advantage for some heavy shipments that were not time sensitive, but for other shipments trucks became the preferred mode of transport. The current system, with its roughly 21,000 km of track, is far less important to Mexico’s economy than it was a century ago.

Related posts:

- The development of railways led to tourist guide books

- The Ghost Train (El Tren Fantasma): a case study of the geography of sound in Mexico

- Mexico’s Copper Canyon train is one of the world’s great railway trips

- Yucatán’s independent sisal railroad system

- Cuautla, Mexico, has the world’s oldest railway station building