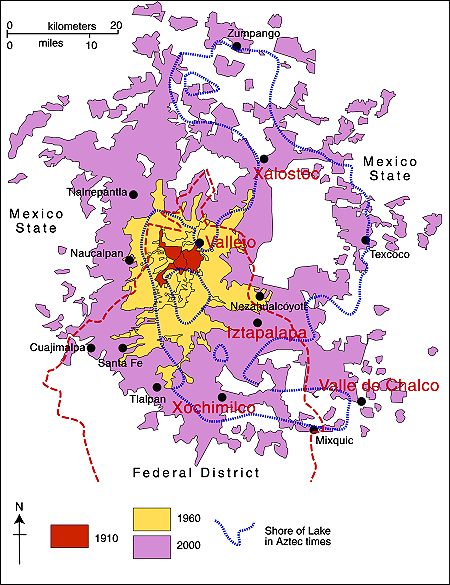

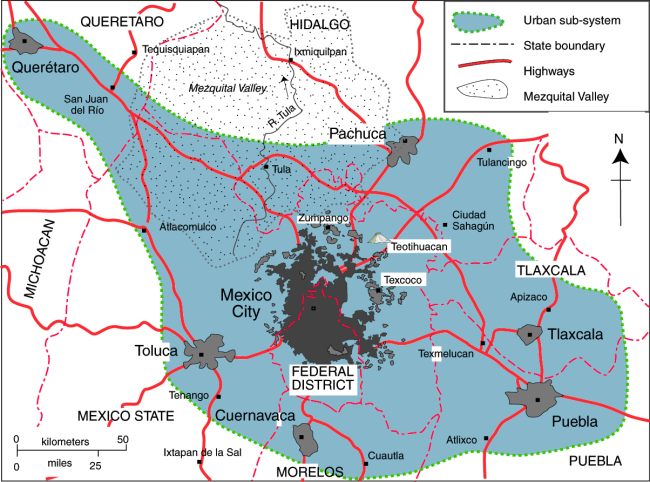

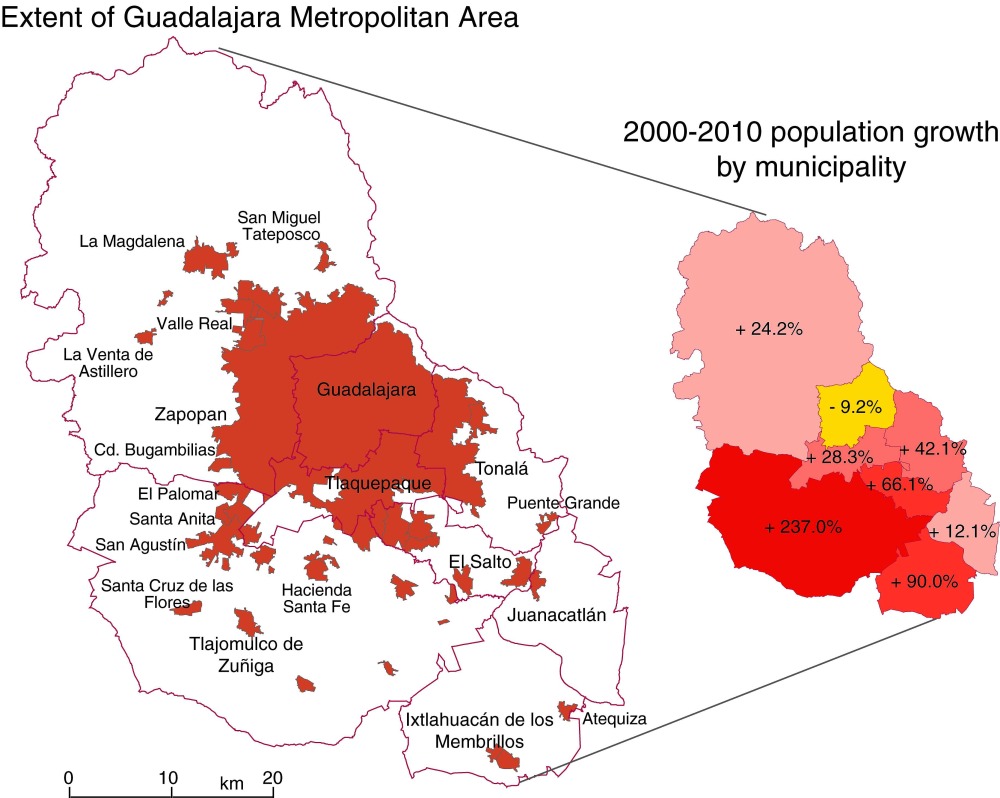

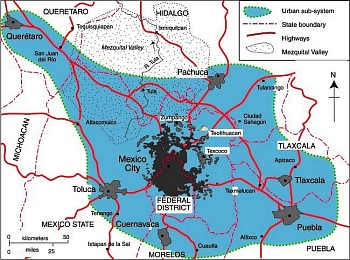

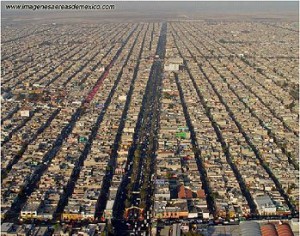

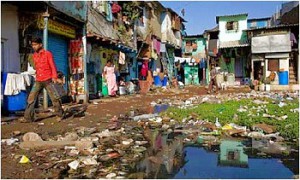

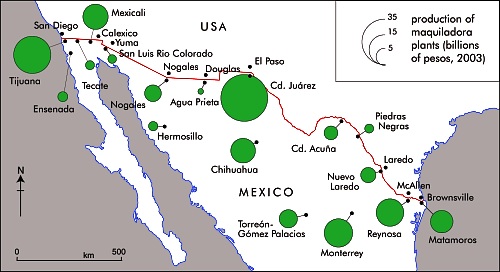

More than 200 homes in the low-income settlement of Valle de Chalco on the south-eastern edge of Mexico City, in the State of México, were flooded by raw sewage last month. The affected homes were in San Isidro and La Providencia, in Valle de Chalco (see map).

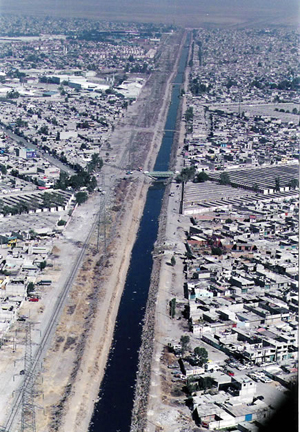

At least 500 residents faced a grim clean-up following several days of flooding. The problem was caused by a 30-meter-long crack in a surface sewage canal known as the Canal de la Compañia. The crack allowed 6,000 cubic meters a second of raw sewage to inundate nearby streets and homes. The federal water authority, Conagua, said that it would take three weeks to complete repairs to the canal wall.

The canal wall is thought to have been put under too much pressure due to the unfortunate combination of unusually heavy rains and a blockage occasioned by accumulated garbage such as plastic bags. It is possible that continued ground settling –More ground cracks appearing in Mexico City and the Valley of Mexico – also contributed to the problem. José Luis Luege Tamargo, the head of Conagua, placed much of the blame for the most recent flooding on the local municipal authorities of Ixtapaluca for not having ensured that no garbage was dumped anywhere in or near the Canal.

The 260 families and small businesses affected were all given some immediate financial assistance via 20,000-peso payment cards valid at any Soriano supermarket. In addition, authorities have pumped out basements and begun an emergency vaccination campaign.

The Canal de la Comañia’s walls have failed three times in the past decade, with serious flooding each time; the most recent disaster was in February 2010, when 18,000 people were forced to flee the rising wastewater. Conagua has reportedly proposed a more permanent remedy involving the rerouting of 7 km (almost 5 miles) of canal. The project would take two years to complete, with an estimated cost of 300 million pesos ($25 million).