This little 77-page gem only recently came to my attention, but is sufficiently interesting, for lots of different reasons, to make it well worth reading if you have the chance.

Written in straightforward, non-academic language, Stanislawski sets about unpacking the factors explaining the land use patterns for eleven towns in the western Mexico state of Michoacán. Stanislawski knows the land use patterns of these town, because he painstakingly compiled them, with the help of multiple informants in each town, in the 1940s.

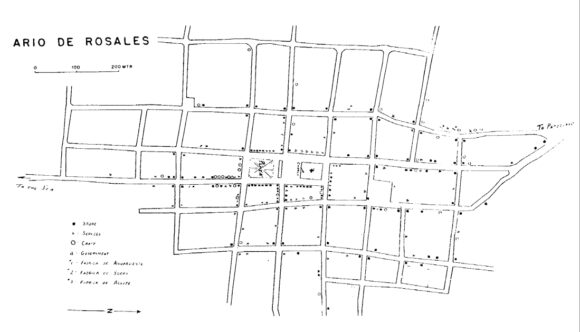

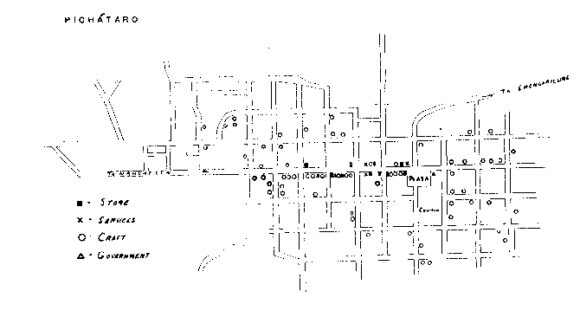

Stanislawski explains that his purpose was to find a method that would reliably identify the “personality differences” that he had intuitively recognized, during earlier fieldwork, for towns in Michoacán. He set out to map the four distinct categories of land use – stores, crafts, administrative offices and services – that he thought would likely reveal the “distributional aspects that might indicate differences between towns.”

He assumed that each town would be influenced by its geographic area, and therefore chose eleven towns that he thought would be a systematic sample: one in the coastal lowlands, three in the low Balsas valley, two in the upper Balsas valley (close to the temperate slopes), four within the mountain ranges of the volcanic area of Michoacán, and one at an elevation of 2400 m (8000 ft).

The maps he produced revealed that “the geographical region could not explain the differences between the towns except in part.” At least as important, Stanislawski decided, was which of the two basic cultural groups – Hispanic or Indian – was predominant in the town. He proposed a threefold classification: Hispanic, Indian or dual-character.

On this basis, Aria de Rosales (upper map), with its imposing plaza the focus of most commercial activity, is an Hispanic town. On the other hand, Pichátaro (lower map), where the plaza is unimportant, is Indian. Of course, these differences, identified by Stanislawski in the 1940s, do not necessarily apply today. Since the 1940s, transport systems have changed, there have been waves of migration out of many Michoacán towns, and the range of economic activities in towns has increased significantly, with a trend away from primary activities and a sharp rise in tertiary 9service) activities.

In the 1980s (sadly ignorant at the time of Stanislawski’s work), I employed a small army of geography students to undertake a somewhat similar mapping exercise in various Michoacán settlements, ranging in size from the small village of Jungapeo to the mining town of Angangueo and the large city of Zitácuaro. For an example of this kind of work, see The distribution of retail activities in the city of Zitácuaro, Michoácan, Mexico. Sadly, those 1980s maps were later discarded during a clean-out of the department map cabinet by a well-intentioned, if ill-informed, successor.

Source:

- The Anatomy of Eleven Towns in Michoacán (review) by Dan Stanislawski (University of Texas, Institute of Latin American Studies, Latin American Studies X, 1950); reprinted by Greenwood Press, New York, 1969.