Prior to European contact in 1519, what did the Aztec people eat?

The basis of Aztec diet was corn (maize). They cultivated numerous varieties of corn, as well as many other crops including beans, amaranth and squash. Some dishes were seasoned with salt and chili peppers. This mix of items provided a balanced diet that had no significant vitamin or mineral deficiency.

In addition, the Aztec diet included tomatoes, limes, cashews, potatoes, sweet potatoes, peanuts, cacao (chocolate), wild fruits, cactus, mushrooms, fungi, honey, turkey, eggs, dog, duck, fish, the occasional deer, iguana, alongside insects such as grasshoppers. From the lake water, they scooped high protein algae (tecuitlatl), which was also used as a fertilizer.

How did they obtain their food?

The Mexica (who later became the Aztecs) faced a particular dilemma, largely of their own making. Mexica (Aztec) legend tells that they left their home Aztlán (location unproven) on a lengthy pilgrimage lasting hundreds of years. They were seeking a specific sign telling them where to found their new capital and ceremonial center. The sign was an eagle, perched on a cactus. Today, this unlikely combination, with the eagle now devouring a serpent, is a national symbol and appears on the national flag.

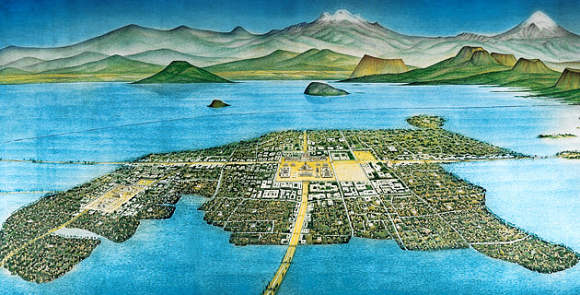

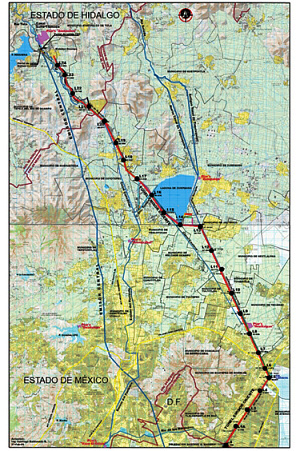

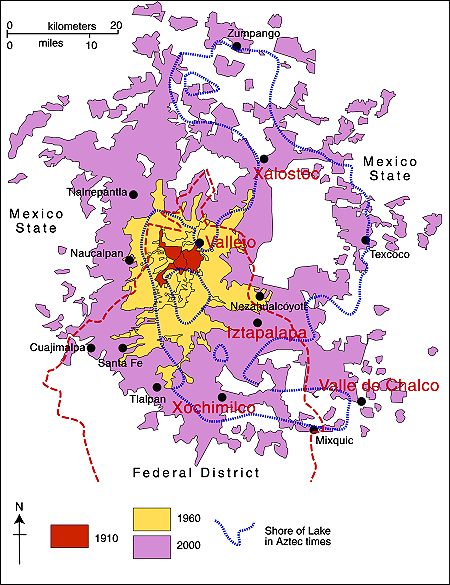

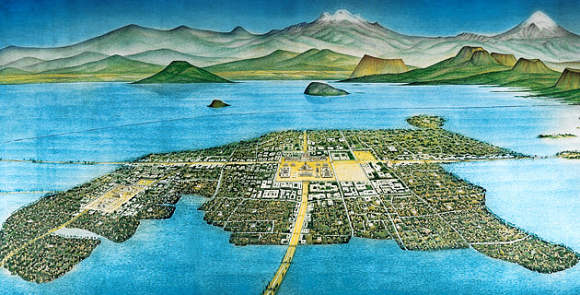

Artist’s view of the Aztec capital Tenochititlan in the Valley of Mexico

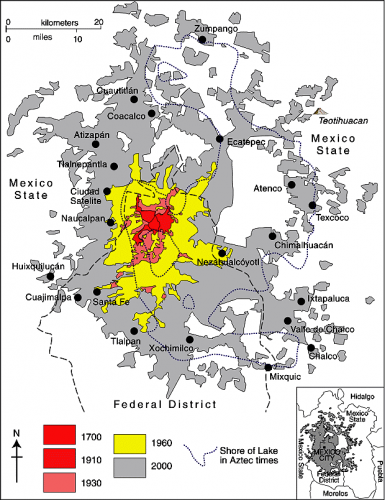

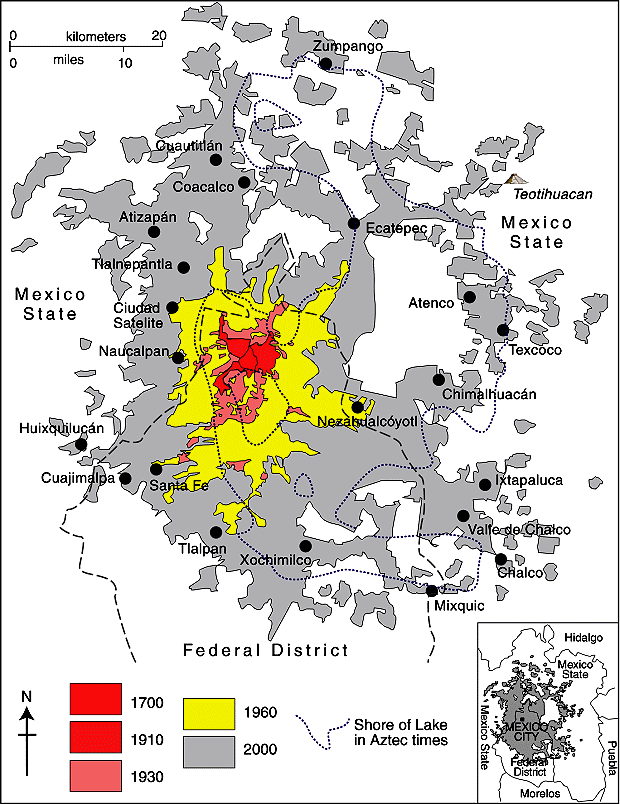

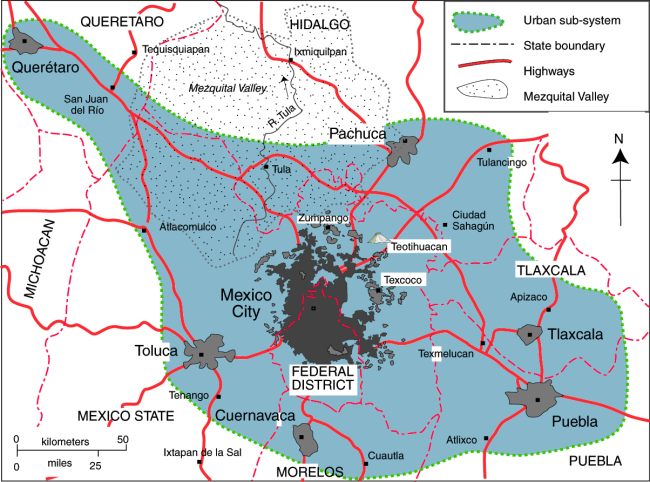

The dilemma arose because they first saw this sign, and founded their new capital Tenochtitlan, on an island in the middle of a lake in central Mexico. An island linked by causeways to several places on the “mainland” might have had some advantages in terms of defense, but supplying the growing settlement with food and fresh water was more of a challenge.

Much of their food came from hunting and gathering, and some food was brought by long-distance trade, but space for farming, especially on the island, was at a premium.

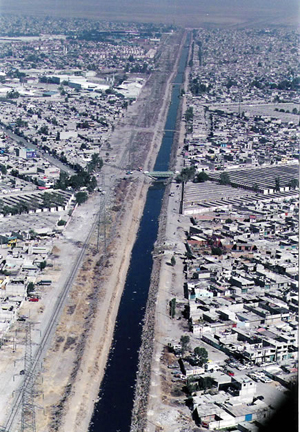

The Aztecs solved their dilemma of how to supply food to their island capital by developing a sophisticated wetland farming system involving raised beds (chinampas) built in the lake (see image below). Originally these chinampas were free-floating but over time they became rooted to the lake floor. The chinampas were separated by narrow canals, barely wide enough for small boats or canoes.

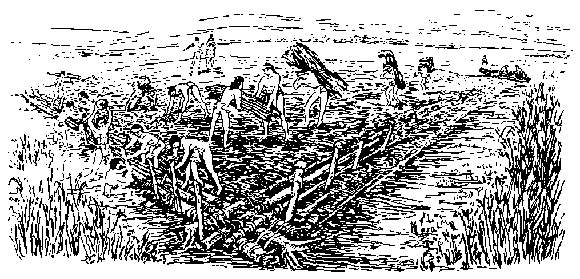

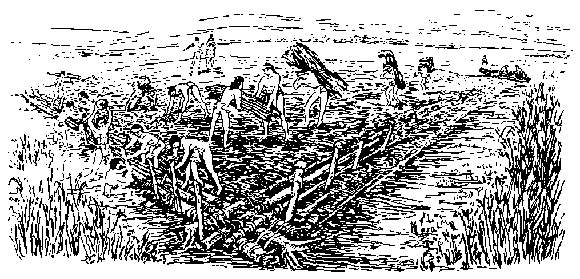

Artist’s representation of chinampa farming

From an ecological perspective, these chinampas represented an extraordinary achievement, a food production system which proved to be one of the most environmentally sustainable and high-yielding farming systems anywhere on the planet!

Constructing and maintaining chinampas required a significant input of labor, but the yields per unit area could be very high indeed, especially since four harvests a year were possible for some crops. The system enabled fresh produce to be supplied to the city even during the region’s long dry season, whereas food availability from rain-fed agriculture was highly seasonal.

Artist’s interpretation of chinampa construction (from Rojas 1995)

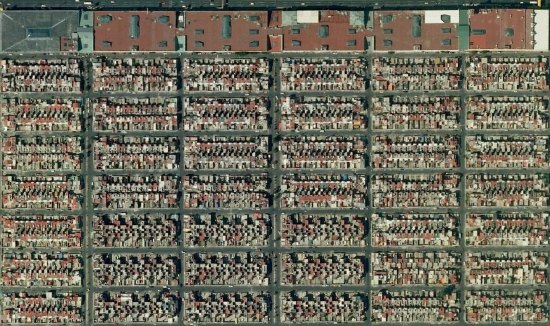

The planting platforms or chinampas were built by hand, with alternate layers of mud, silt and vegetation piled onto a mesh of reeds or branches. Platforms, often but not necessarily rectangular, were about 10 meters wide and could be 100 meters or more in length. Willow trees were often planted on the edges of platforms to help stabilize them and provide shade for other plants and for the canals that separated the platforms. Interplanting crops was common, and polyculture was the norm. For many crops, multicropping (several crops in a single year) was possible.

Because the planting platforms were close to water, extremes of temperature were dampened, and the likelihood of frost damage to crops reduced. The root systems of crops had reliable access to fresh water (sub-irrigation). The canals provided a variety of habitats for fish. The mud from the bottom of canals was periodically dredged by hand and added to the platforms, supplying nutrients and preserving canal depth. Together with the regular addition of waste organic material (compost), this replenished the platforms and meant that their fertility was maintained over very long periods of time.

The system could even cope with polluted water, since the combination of constant filtration on the platforms, and aquatic weeds in the canals, partially removed most impurities from the water.

Where can chinampas be seen today?

Archaeologists have found vestiges of chinampas in several regions of Mexico, some dating back almost 3000 years.

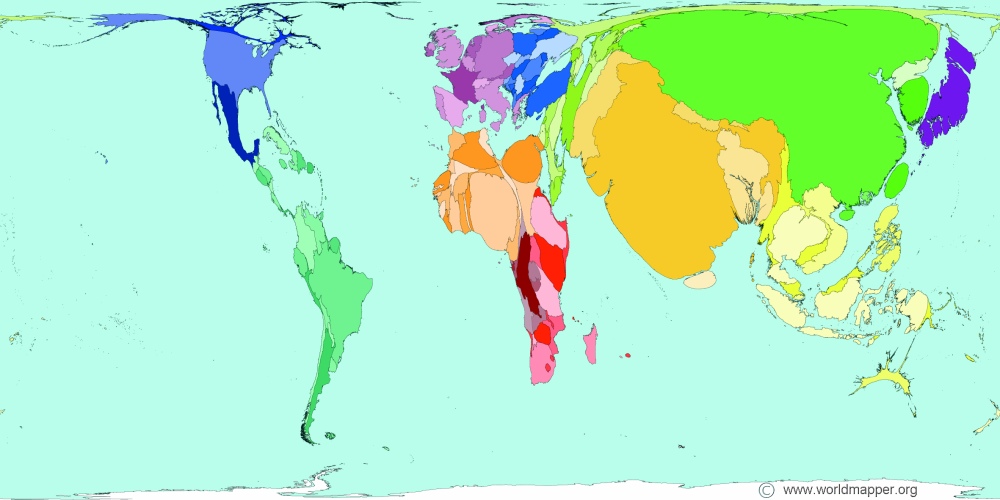

Mexico’s best known chinampas today are those in Xochimilco on the south-eastern outskirts of Mexico City. Xochimilco is a Unesco World Heritage site, but faces heavy pressure from urban encroachment and highway construction. Xochimilco’s canals (with chinampas separating them) are some of the last surviving remnants of the large lake that occupied this valley when the Mexica founded Tenochititlan.

Xochimilco (Wikipedia; creative commons)

Visiting Xochimilco’s canals and market is a popular weekend excursion for Mexico City residents and tourists alike. However, the modern-day chinampas of Xochimilco are not the same as they would have been centuries ago. First, the total area of chinampas in Xochimilco is only a fraction of what once existed. Secondly, some of the chinampas have been abandoned, while on others chemical fertilizers and pesticides are often used. Thirdly, the area now has many exotic species, including introduced species of fish (such as African tilapia and Asian carp) that threaten native species. Numbers of the axolotl (a local salamander), a prized delicacy on Aztec dinner tables, are in sharp decline. Fourthly, the water table in this area fell dramatically during the last century as Mexico City sucked water from the underground aquifers causing local springs that helped supply Xochimilco to dry up completely. Rubble from the 1985 Mexico City earthquake was also dumped in Xochimilco’s canals.

Lakes in some other parts of Mexico were also used for chinampa farming. For example, in Jalisco, just west of Guadalajara, Magdalena Lake “was a prime source of food for the 60,000 or so people living close to the Guachimontones ceremonial site (settled before 350 BC) in Teuchitlán. They learned to construct chinampas, fixed mud beds in the lake, each measuring about 20 meters by 15 meters, which they planted with a variety of crops… The remains of hundreds of these highly productive islets are still visible today.” (Western Mexico: A Traveler’s Treasury, p 69)

Chinampa farming was one of the great agricultural developments in the Americas. It was, and still can be, an environmentally-sensitive and sustainable method of intensive wetland agriculture.

If you enjoyed this…

You might well enjoy my latest book: Mexican Kaleidoscope: myths, mysteries and mystique

Want to read more?

Related posts