Foreigners are defined as individuals born in another country, but residing in Mexico. According to the recent census, almost a million (961,121) foreigners were living in Mexico in mid-2010. In 2000 there were only about half as many (492,617). Among foreigners, there were slightly more males than females (50.6% versus 49.4%). Under this definition, children born in the USA of two Mexican parents are considered foreigners if they currently live in Mexico. Unfortunately, the data currently available do not enable us to separate these foreign-born Mexicans from other foreigners who were raised in other countries and moved to Mexico to follow their professions or retire. Furthermore, they do not help us answer a question we have been asked dozens of times in recent years, namely, “How many Canadians and how many Americans have retired in Mexico?”

Though almost a million foreigners sounds like an impressive number, Mexico has relatively few foreign born residents compared to its two northern neighbors. Foreigners constitute only 0.86% of the 2010 Mexican population, compared to 21% Canada and 13% in the USA.

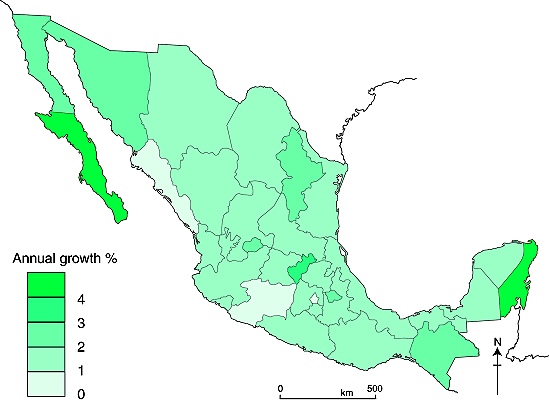

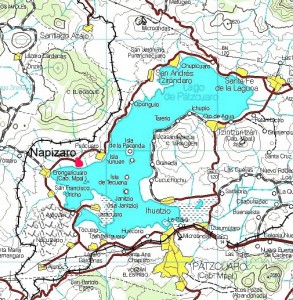

Where in Mexico do most foreigners reside? Baja California has the most foreigners with almost 123,000, followed by Jalisco (84,000), Chihuahua (80,000), and the Federal District (72,000). Tlaxcala has the fewest, with just over 3,200, followed by Tabasco with about 4,500.

The states with the highest percentage of foreigners are mostly along the US border. Baja California leads with 3.9%, followed by Chihuahua (2.3%), Tamaulipas (1.9%), and Sonora (1.7%). Interestingly, the other border state, Coahuila, has relatively few foreigners, only 0.8%. Other states with relatively large percentages are either historical sources of immigrants to the USA or retirement havens like Colima (1.44%), Quintana Roo (1.40%), Nayarit (1.35%), Zacatecas (1.22%), Jalisco (1.14%) and Michoacán (1.10%).

Tabasco has the fewest foreigners as a percentage with only 0.20%, followed by Tlaxcala (0.28%), Veracruz (0.30%), the State of México (0.33%) and Yucatán (0.36%). Yucatán is a surprise on this list because there is a very large and active foreign retirement community there. Perhaps many of these retirees were away from Mexico when the census was taken in the summer of 2010.

What states experienced the largest increases in foreigners in the last decade? The number of foreigners grew fastest in those states with relatively few foreigners in 2000, namely Hidalgo (up 402% over the decade), Tlaxcala (333%), Tabasco (281%), and Veracruz and Oaxaca (both with 272%).

Related posts: