An earlier post looked at why Mexico’s coffee harvest was unlikely to meet expectations this year. The 2010-11 harvest, hit by poor weather, totaled a disappointing 4 million 60-kg sacks (240,000 metric tons), almost entirely Coffea arabica and about 70% destined for export. This post looks at some recent trends relating to the production and consumption of coffee in Mexico.

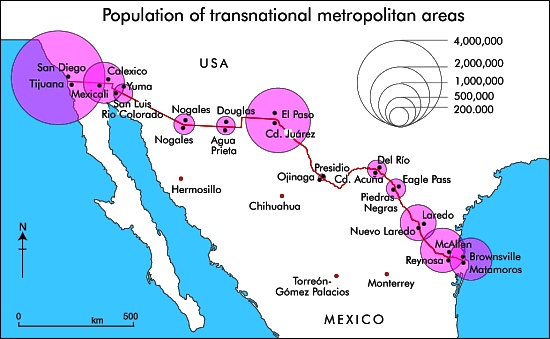

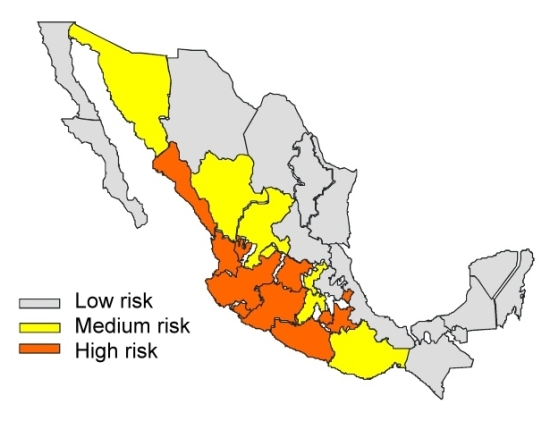

Mexico is the world’s seventh largest coffee producer (after Brazil, Vietnam, Indonesia, Colombia, India and Ethiopia) and one of the leading suppliers of organic, shade-grown coffee. The nation’s 480,000 coffee growers, most working small parcels of land less than 5 hectares (12 acres) in size, are concentrated in the states of Chiapas, Veracruz and Oaxaca.

Mexico’s domestic consumption of coffee

Despite being one of the world’s leading coffee producers,Mexico’s domestic consumption averages only 1.2 kg (2.6 lbs) per person each year. While this figure has doubled since 2000, is is still only about half the equivalent figure for the coffee-growing Central American nations, and way below consumption in wealthier countries such as world-leader Finland (12 kg per person) or the USA (5.5 kg per person). Domestic consumption is rising but remains low.

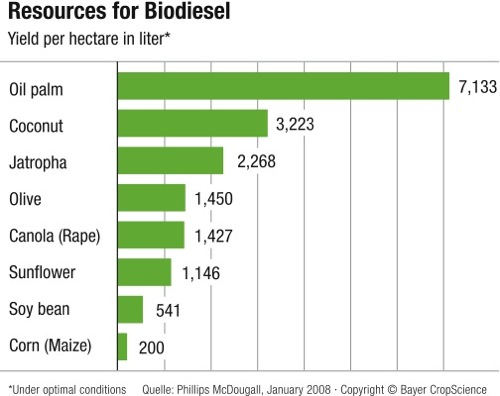

Yields need to rise

According to Amecafe (Asociación Mexicana de la Cadena Productiva del Café), a major growers’ organization, global climate change is expected to have an adverse long-term effect on prices and on the sustainability of coffee-farming in Mexico. In an effort to raise yields of coffee to at least 12 quintals/hectare (19 bushels/acre) within 3 years and to 20 quintals/ha (32 bushels/acre) eventually, Mexico’s Agriculture Secretariat has announced financing of 16 million dollars for a program to gradually replace aging coffee groves in 12 states.

Fair trade coffee faces uncertain future

Soaring coffee prices might signal the beginning of the end for Fair Trade coffee. Much of the world’s specialty coffee comes from small-scale growers in Latin America, including Mexico, and much of it is marketed as “organic” or “fair trade”. After a decade of depressed prices, wholesale and retail prices for coffee have risen sharply in the past year. US retail prices have risen more than 20%; the price of coffee on international commodity markets has risen almost 60%.

The higher prices should be good news for growers, but as Kevin Hall points out in “Coffee prices being pushed by speculators” this is not necessarily the case. Many co-operative marketing organizations, including those considered socially-responsible or “Fair Trade”, do not have the resources to pay the new higher prices and acquire sufficient coffee to meet their existing contracts. This means they can no longer compete against the well-financed middlemen who specialize in purchasing coffee for regular distribution via commodities markets and major buyers. Farmers want the maximum return they can get on their crop, and they want it on delivery, which makes life difficult for any fair trade co-operative that lacks strong financial resources.

Further statistics:

- USDA (US Department of Agriculture) June 2011 update on coffee (pdf file).

Related post:

Jacques Cousteau

Jacques Cousteau