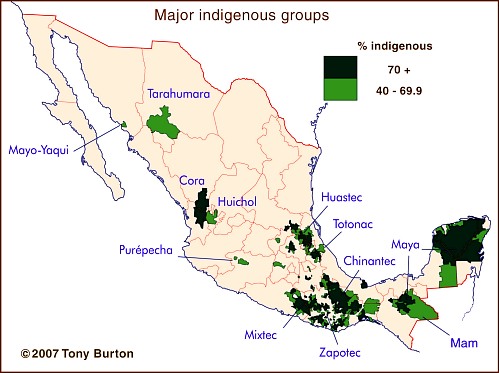

The growth of Protestantism in Mexico has been rapid among low income groups, particularly in poor states and indigenous areas. Many of these gains are considered less a conversion from true Catholicism than a first time acceptance of a modern religion by people who previously adhered to Indian Folk Catholicism. Protestantism, and especially Pentecostalism, is thought to be compatible with indigenous values and spiritual practices. Some Protestant groups have specifically focused their proselytizing efforts in indigenous areas.

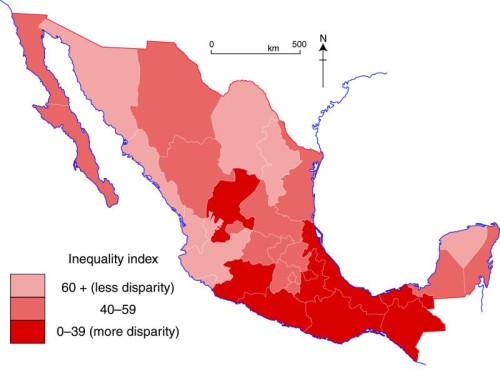

The Mexican census divides non-Catholic churches into two groups. The first, “Protestant and Evangelical,” includes about 5% of Mexicans. The percentage varies from less than 2% in western Mexico to over 10% in southeastern Mexico. Pentecostal and Evangelical churches now make up 85% of this group. Dozens of Evangelical denominations have engaged in strong recruitment efforts since 1970, with considerable success in southeastern Mexico. In 2000, Protestants and Evangelicals comprised 14% of the population in Chiapas and Tabasco, 13% in Campeche, and 11% in Quintana Roo. The 2010 census is expected to show a significant increase in these percentages. This group also includes Lutheran, Methodist, Presbyterian, Mennonites and Luz del Mundo, a Protestant denomination founded in Mexico.

The second non-Catholic group, “Biblical, not Evangelical,” is still rather small, but has grown very rapidly in the past two decades. It includes the Seventh Day Adventist Church, which is particularly popular in indigenous areas, as well as Jehovah’s Witnesses, which have so far had little influence in indigenous areas. Also in this group is the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Mormons), which first arrived in Mexico in 1875. Several English-speaking Mormon colonies were established in Chihuahua (Colonia Juárez is the most prominent today) and Sonora. As a result of impressive proselytizing efforts, Mormon membership surged from 248,000 in 1980 to 617,000 in 1990 and more than 1 million in 2005. Mexicans belonging to the Mormon Church have, on average, much higher incomes, higher rates of literacy and, interestingly, lower fertility rates than members of other churches.

The geography of Mexico’s religions is discussed in chapter 11 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico.

Previous posts in this mini-series on the geography of religion in Mexico: