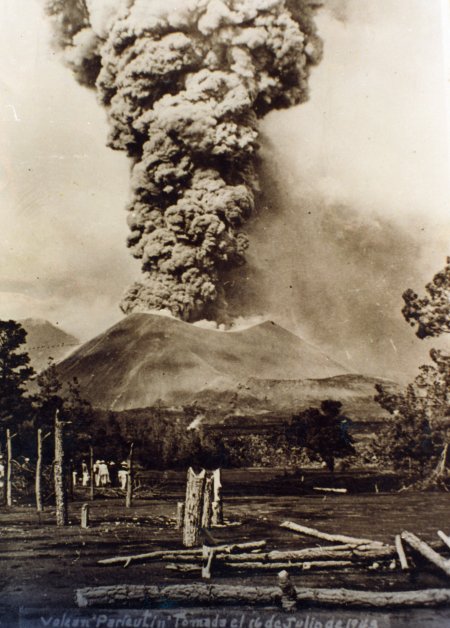

Today (20 February 2013) marks the 70th anniversary of the first eruption of Paricutín Volcano in the state of Michoacán in western Mexico.

The landscape around the volcano, which suddenly started erupting in the middle of a farmer’s field in 1943 and which stopped equally abruptly in 1952, is some of the finest, most easily accessible volcanic scenery in the world. A short distance northwest of Uruapan, this is a geographic “must see”, even if you can only spare a few hours.

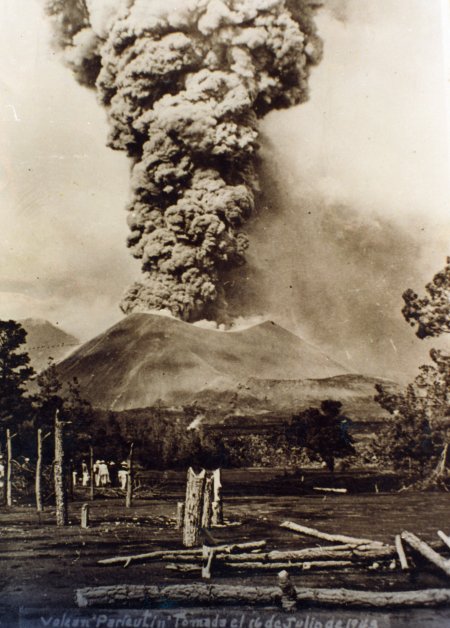

Paricutín Volcano, 16 July 1943

What makes Paricutín so special is that in all of recorded history, scientists have had the opportunity to study very few completely new volcanoes in continental areas (whereas new oceanic island volcanoes are comparatively common). The first two new volcanoes formed in the Americas in historic times are just one hundred kilometers apart. The first was Jorullo, which erupted in 1759, and the second is Paricutín.

Dominating the valley where Paricutín now exists is the peak of Tancítaro, the highest point in the state of Michoacán at 3845 meters (12,615 feet), and sometimes snow-capped in winter. In 1943, the local Purépechan Indians inhabited a series of small villages and towns spread across the valley floor. The villages included Angahuan, which still exists today, Paricutín, where all 500 people lost their homes, and San Juan Parangaricutiro. The latter was once famous for hand-woven bedspreads and quilts and consequently known as San Juan de las Colchas (bedspreads). Its church, begun in 1555, had never been finished and only ever had a single tower.

On 20 February 1943, a local campesino named Dionisio Pulido was tending his crops with his wife Paula, their son and a friend. At about 4:00pm, they noticed a small crack and felt the ground shaking under their feet. While they watched, the ground rose more than 2 meters and smoke rose into the air, accompanied by whistling noises and the smell of sulfur. Sparks set fire to a nearby pine tree. Not surprisingly, they fled!

Legend has it that Dionisio first tried to smother the emerging volcano with loose rocks and afterwards was of the opinion that the volcano would never have erupted if he hadn’t plowed his field, but such reports are almost certainly pure fiction.

The volcano grew rapidly, providing onlookers, visiting vulcanologists and residents alike, with spectacular fireworks displays. The month of March was a particularly noisy time in Paricutín’s history—explosions were heard as far away as Guanajuato and ash and sand were blown as far as Mexico City and Guadalajara.

After one week, the volcano was 140 meters high, and after six weeks 165 meters.

In April 1943 there were major lava flows, originating from about 10 kilometers underground. These lavas were basaltic; their chemistry suggested temperatures inside the volcano of between 960o and 1020oC. More than 30 million metric tons of lava flowed from the volcano between April and June 1943, raising the volcano’s height to more than 400 meters before its first birthday.

In early 1944, another lava flow streamed in a gigantic arc reaching the outskirts of the town of San Juan Parangaricutiro. Fortunately, the town had already been abandoned following many earthquakes, some of which rang church bells as far away as Morelia! The lava flowed about 30 meters a day and went right through the church but, miraculously, left the main altar standing. The parts of the church which survived in “old” San Juan, including its altar, can still be visited today, though reaching them involves clambering over jagged blocks of lava.

The villagers who had abandoned the town were escorted to Uruapan for safety. Some of them later founded a new town called San Juan Nuevo. Other villagers moved away to live in Los Reyes, Uruapan, Angahuan, Morelia and Guadalajara.

Yet another lava flow buried the village of Paricutin which fortunately had also been evacuated in time. Nothing remains of this village, covered by lava which is more than 200 meters thick in places! A small cross atop the lava marks its approximate position. Besides lava, ashes and dust were also thrown out by the volcano. The ash was 1 millimeter thick in Guadalajara, 25 centimeters thick in Angahuan, and 12 meters thick near the cone. The volcano rose 410 meters above the original ground surface.

Suddenly, in February 1952, nine years after the volcano first erupted, the lava stopped flowing. In many places, plumes of hot steam still rise as fumaroles from the ground, ground that is still most distinctly warm to the touch.

Enjoying a full day at Paricutín has been made much easier since the construction of rustic tourist cabins on the edge of Angahuan village. The restaurant, which serves tasty local specialties, gives clients a panoramic view encompassing the lava and the half-buried church. A small permanent exhibition of maps, charts and photographs in one of the cabins, describing the volcano’s history and the surrounding area, was inaugurated in February 1993 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the volcano.

Horses can be hired for a trip to the church or to the more distant cone of the volcano. The latter requires an early start since the last part involves clambering up the loose ashes and cinders which comprise the cone and scrambling onto the narrow rim of the truly magnificent crater. A marvelous view can be enjoyed from atop the crater rim and only then can the full extent of the area devastated by the volcano be fully appreciated. Nothing can quite have prepared you for this startling lunar-like landscape.

Note:

This post is a lightly edited extract from my “Western Mexico: A Traveler’s Treasury” (Sombrero Books, 2013). Chapter 35 describes Paricutín Volcano and its surrounding area, including the fascinating indigenous village of Angahuan, in much more detail. “Western Mexico: A Traveler’s Treasury” is also available as either a Kindle edition or Kobo ebook.

Related posts: