Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is natural gas which has been processed to allow for transportation to international markets well beyond the reach of pipelines. The process enables major producers of natural gas such as Australia, Qatar, Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei, Abu Dhabi and Oman to supply markets almost anywhere in the world.

The stages involved in making and shipping LNG are:

- 1. Natural gas is extracted from underground deposits.

- 2. The gas is sent to a processing plant where impurities such as water, oil and carbon dioxide are removed (a process known as sweetening).

- 3. The purified gas is cooled to minus 162 degrees C (the temperature of the surface of Saturn). This is accompanied by a dramatic decrease in its volume. The process turns 615 liters of natural gas into a single liter of LNG.

- 4. The super-cold LNG is kept cold by storage in cryogenic tanks. LNG in this form is not explosive and cannot burn, making it safe to transport.

- 5. LNG is then transported to markets in special tanks aboard double-hulled tankers. Modern tankers can each transport 50,000 metric tons of LNG.

- 6. At the market, LNG is put in special tanks where it is allowed to warm up, becoming gaseous again. This gas can then be piped to consumers.

Worldwide, there are currently 17 liquefaction gas terminals preparing LNG for export, and 40 terminals where imported LNG can be reconverted, 35 of them in Japan.

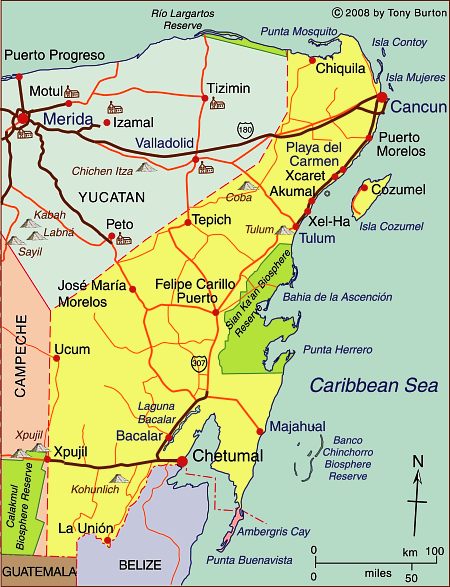

Mexico has two existing regasification plants, as well as one currently under construction and several more in the planning stages. Mexico’s first three terminals are in:

- Altamira, Tamaulipas – this plant opened in 2006 and may be expanded in 2012

- Ensenada, Baja California – this plant which is 14 miles north of Ensenada opened in 2008

- Manzanillo, Colima – currently under construction, expected to open in 2011/12

Proposed LNG regasification plants in Mexico are being considered for:

- Puerto Libertad, Sonora – 60% of the output from this terminal would be piped to the USA, the remainder to cities in northern Mexico

- Topolobampo, Sinaloa – planned opening date is 2016

- Offshore of Tamaulipas, in the Gulf of Mexico – this plant would be built 35 nautical miles offshore

- Lázaro Cárdenas, Michoacán – the proposed LNG terminal would be close to the existing major port

- Salina Cruz, Oaxaca

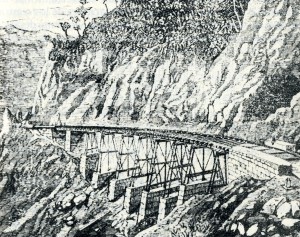

LNG means that industries and homes far from Mexico’s own gas fields which are mainly in the north-east of the country can still have access to gas. Supplying them direct from Mexico’s gas fields would require the construction of costly series of pumping stations and pipelines crossing the rugged Western Sierra Madre (Sierra Madre Occidental), where any construction of this kind would be very difficult.