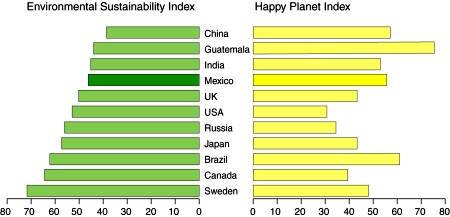

Chapter 30 of Geo-Mexico, the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico includes a look at the Happy Planet Index (HPI). The HPI is a compound index that combines three measures:

- life expectancy

- life satisfaction

- ecological footprint

In essence, the HPI shows how successfully people are achieving the good life without having to consume a disproportionate share of the Earth’s resources. The unbridled global pursuit of economic growth over the past fifty years has left more than a billion people in dire poverty. Far from bringing economic stability, it has encouraged the rampant abuse of resources while increasing the very real risks of unpredictable global climate change.

The HPI attempts to quantify an alternative vision of progress where people strive for happy and healthy lives alongside ecological efficiency in how they use resources. A high HPI score is only possible if a country is close to meeting the targets for all three components.

Environmental Sustainability Index and Happy Planet Index for selected countries. (Geo-Mexico. Figure 30.4) All rights reserved.

HPI scores (see graph) paint a very different picture to that suggested by either the ecological footprint or the Environmental Sustainability Index (ESI). While happy and healthy lives often go hand in hand, many countries with high values for those components (such as the USA and Canada) have disappointingly high ecological footprints, and end up with low HPI scores. The lowest HPI scores of all are found in sub-Saharan Africa where several countries do badly on all three components.

At the other end of the scale, nine of the top ten HPI scores are for countries in Latin America and the Caribbean where relatively high life expectancy and high personal lifestyle satisfaction is combined with modest footprints. Mexico ranks 22nd of the 151 countries studied, behind Argentina and Guatemala but well ahead of the UK, Canada and the USA.

Life expectancy

The life expectancy figure for each country was taken from the 2011 UNDP Human Development Report and reflects the number of years an infant born in that country could expect to live if prevailing patterns of age-specific mortality rates at the time of birth in the country stay the same throughout the infant’s life.

Mexico’s life expectancy is 77.0 and ranks #36 among the 151 countries analyzed. This is below the USA, which has a life expectancy of 78.4, but higher than Malaysia, which has a life expectancy of 74.2.

Life satisfaction

The data for life satisfaction (experienced well-being) draws on responses to the ladder of life question in the Gallup World Poll, which was asked to samples of around 1000 individuals aged 15 or over in each of the countries included in the Happy Planet Index.

Mexico’s experienced well-being score is 6.8 out of a possible 10. This is lower than the average level of experienced well-being in the USA (7.16), but higher than that of Germany (6.72).

Ecological footprint

Ecological Footprint is a metric of human demand on nature, used widely by NGOs, the UN and several national governments. It measures the amount of land required to sustain a country’s consumption patterns. For a majority of the countries (142 of the 151), Ecological Footprint data were obtained from the 2011 Edition of Global Footprint Network National Footprints Accounts. For the nine other countries, Ecological Footprint figures were estimated using predictive econometric models.

Mexico’s Ecological Footprint is 3.30 global hectares per capita. If everyone in the world had the same Ecological Footprint as the average citizen of Mexico, the world’s Ecological Footprint would be 20% larger and we would need to reduce our Ecological Footprints by around 80% in order to stay within sustainable environmental limits.

Summary

In summary, countries often considered to be ‘developed’ are some of the worst-performing in terms of sustainable well-being.

Unfortunately, given that the HPI scores for the world’s three largest countries (China, India, and the USA) all declined between 1990 and 2005, it does not seem that the situation is improving or will improve any time soon. Business as usual is literally costing us the Earth.

Related posts:

![birds-ibas-2 Important Bird Areas in Mexico [Birdlife.org]](http://geo-mexico.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/birds-ibas-2.jpg)

Jacques Cousteau

Jacques Cousteau