Remittances (the funds sent by migrant workers back to their families) are a major international financial flow into Mexico. Remittances bring more than 20 billion dollars a year into the economy, an amount equivalent to 2.5% of Mexico’s GDP.

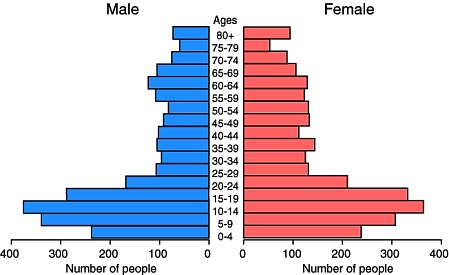

On a per person basis, Mexico receives more worker remittances than any other major country in the world. An estimated 20% of Mexican residents regularly receive some financial support from relatives working abroad. Such remittances are the mainstay of the economies of many Mexican families, especially in rural areas of Durango, Zacatecas, Guanajuato, Jalisco and Michoacán.

The causes and consequences of mass out-migration and large remittance payments are varied, and sometimes disputed. For background, causes and trends, try:

- The US Bracero guest worker program

- The link between climate change and migration from Mexico to the USA

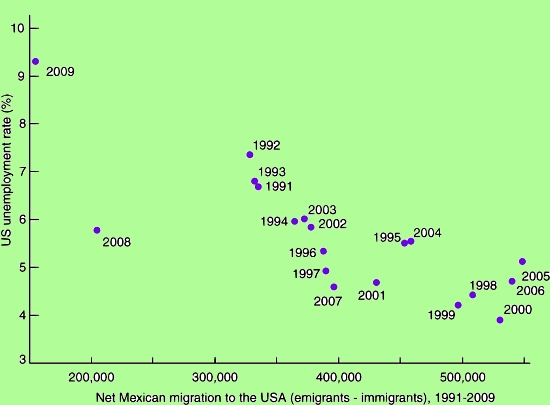

- The impact of the economic recession on Mexico-USA migration

- Remittances sent back to Mexico rose only 0.12% in 2010

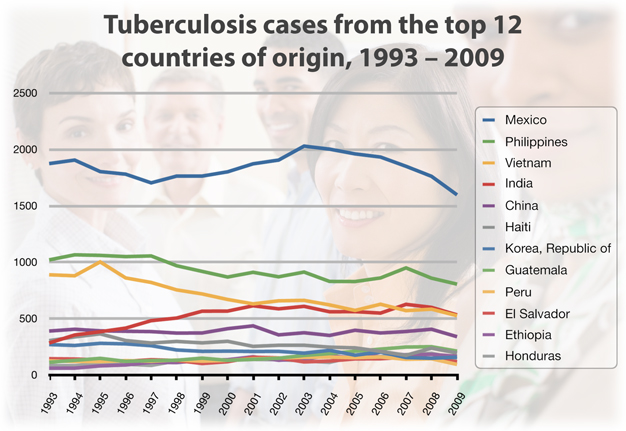

For some impacts of Mexican migrants on the USA (of varying importance), see:

- A round-up of news items about Mexicans in the USA

- Mexican migrants pay 53 billion dollars a year in US taxes

The four subtitles used in the Atlantic Magazine article are useful reminders of some of the other major aspects of international migration from Mexico. Again, links are given to previous Geo-Mexico posts which look at good examples.

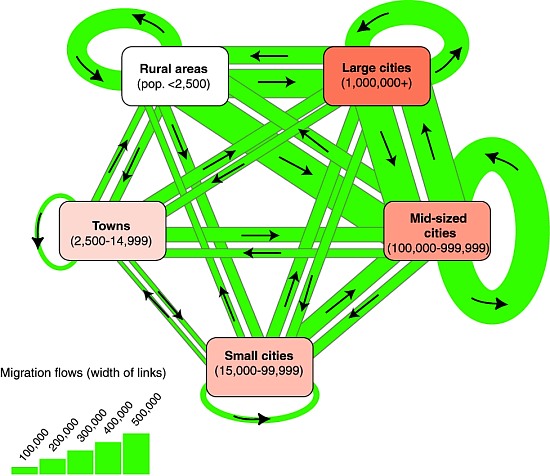

“Branching Out” emphasizes the links that exist between communities, often referred to as “migration channels”.

- Migration channels between Mexico and the USA, or how distant towns are linked through migration

- Over half a million natives of the state of Puebla live in New York City

- From Morelos to Minnesota; case study of a migrant channel between Mexico and USA

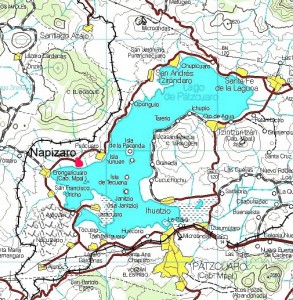

- The connection between Napizaro (Michoacan) and North Hollywood (California)

“The Hollow States” identifies the five major “states of origin”—Guanajuato, Jalisco, Michoacán, San Luis Potosí and Zacatecas—which receive almost 50% of all remittance payments.

- The 10 states in Mexico receiving the highest remittances per person

- The 10 states in Mexico receiving the most remittances in total

- The 10 states in Mexico with the highest percentage of homes receiving remittances

“Staying Put” points out that improved economic conditions in Mexico in recent decades, have restricted out-migration from certain areas, especially the border region. Recent developments in Mexico’s war on drugs have, however, led to an increase in the number of border residents moving to bigger, safer cities further south, or seeking to emigrate to the USA.

- The maquiladora export landscape

- The Transnational Metropolitan Areas of Mexico-USA

- The impact of NAFTA on urban growth in Mexico

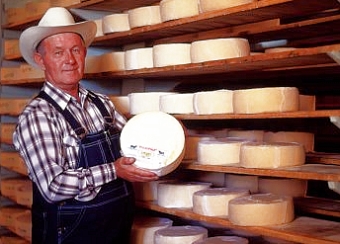

“Community Development” stresses the important link between “hometown associations” (groupings, found in many US cities, of Mexican migrants sharing a common area of origin) and their related villages and towns in Mexico. Many community development projects in areas of high out-migration have been financed by remittances. In many cases, the three levels of Mexican government—municipal, state and federal—provide matching funds for such projects, meaning that remittances only pay for 25% of the total costs.

In future posts, we will examine some of these aspects of remittances in more detail, and take a much closer look at the precise mechanisms used to make the international financial transfers involved.