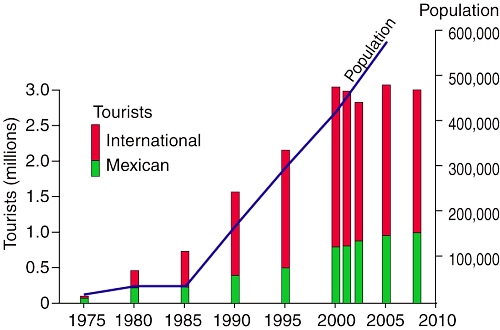

Cancún is Mexico’s premier tourist destination, attracting more than 3 million visitors a year. A recent Associated Press report by Mark Stevenson highlights the problems faced by the resort due to the erosion of its beaches.

Cancún was developed on formerly uninhabited barrier islands on Mexico’s Caribbean coast. The islands were low-lying sand bars, held together by beach vines and the dense, interlocking roots of coastal mangroves. Hurricanes periodically swept over these small islands blowing loose sand towards the beaches on the mainland. Despite the occasional hurricane, the sandbars survived more or less unscathed until construction of Cancún, Mexico’s first purpose-built tourist resort, began in 1970.

As Cancún has grown, so the damage from hurricanes has become more serious. Category 4 Wilma in 2005 was especially destructive.

Why has hurricane damage increased since 1970? Several factors are thought to play in a part in causing the increased rate of erosion of Cancún’s beaches in recent years:

- hotels have been built too close to the shore, and too many are high-rise buildings. High-rise hotels deflect some of the wind downwards towards the ground. These wind eddies can stir up any dry surface sand in a process known as deflation.

- hotels are too heavy. The sheer weight of high-rise hotels compacts the largely unconsolidated sediments beneath them, rendering the sediments less able to store or absorb excess water, and more liable to subsidence and structural problems. Extra weight also increases the load on slopes and leads to a higher incidence of slope failure.

- coastal mangroves have been destroyed, removing their ability to protect the shoreline during storm events.

- most beaches have been stripped of their original vegetation. The original beaches were protected by various adventitious vines which were quick to colonize bare sand. They would simultaneously help hold the sand in place, protecting it from wind action, and gradually add to the organic content of beaches to a point where they could support other, larger plants. Native vegetation has been mercilessly eradicated from Cancún’s beaches to create the tourism “ideal” of uninterrupted swathes of white sand.

It also appears that hurricanes and other tropical storms have become more frequent in recent decades, perhaps as a consequence of global climate change. The situation has also been exacerbated by the gradually rising sea level. Sea level on this coast is rising at about 2.2 mm/y.

Why have some of the efforts made to mitigate the beach erosion only made the situation even worse?

Following strong hurricanes (such as Wilma in 2005) Cancún has lost most of its beaches. The first attempt at beach restoration in 2006 cost 19 million dollars. In 2009, an even costlier (70 million dollar) beach restoration was carried out, using sand dredged from offshore. In one sense, the project was a resounding success. A new beach up to 60 meters wide, was created along some 10 km of coastline.

However, this new beach came at a considerable ecological cost. The pumping of sand from offshore disturbed the seafloor and damaged sealife, including populations of octupus and sea cucumbers. Fine sediments raised by the pumping traveled in suspension to nearby coral reefs, where it also had deleterious impacts.

In addition, the new beach is already being eroded away (some estimates are that up to 8% of the new sand has already been washed or blown away), so presumably if Cancún’s beaches are to be maintained in the future, beach restoration will have to become a regular event.

One hotel erected a breakwater or groyne on its beach to retain all the sand being carried along the coast by the process of longshore drift. The Associate Press article ends with a wonderful story of how the beach in front of this particular hotel was cordoned off by marines last year on the grounds that it was stolen property.

Link to 2013 news article: A fortune made of sand: How climate change is destroying Cancun

Tourism is one of Mexico’s major sources of revenue. But tourism, especially high-rise mass tourism such as that characterized by Cancún, comes with a hefty price tag. Policy-makers need to decide whether this price tag, which will only rise further in the future as we continue to damage our natural environment, is really one that is worth the cost.

- Map of the state of Quintana Roo, with Cancún, Cozumel and Tulum

- The growth of Cancún, Mexico leading tourist resort

Chapter 19 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico looks in much more detail at Mexico’s purpose-built resorts as well as many other aspects of tourism, resorts and hotels in Mexico. Chapter 30 focuses on environmental issues and trends. Buy your copy today!