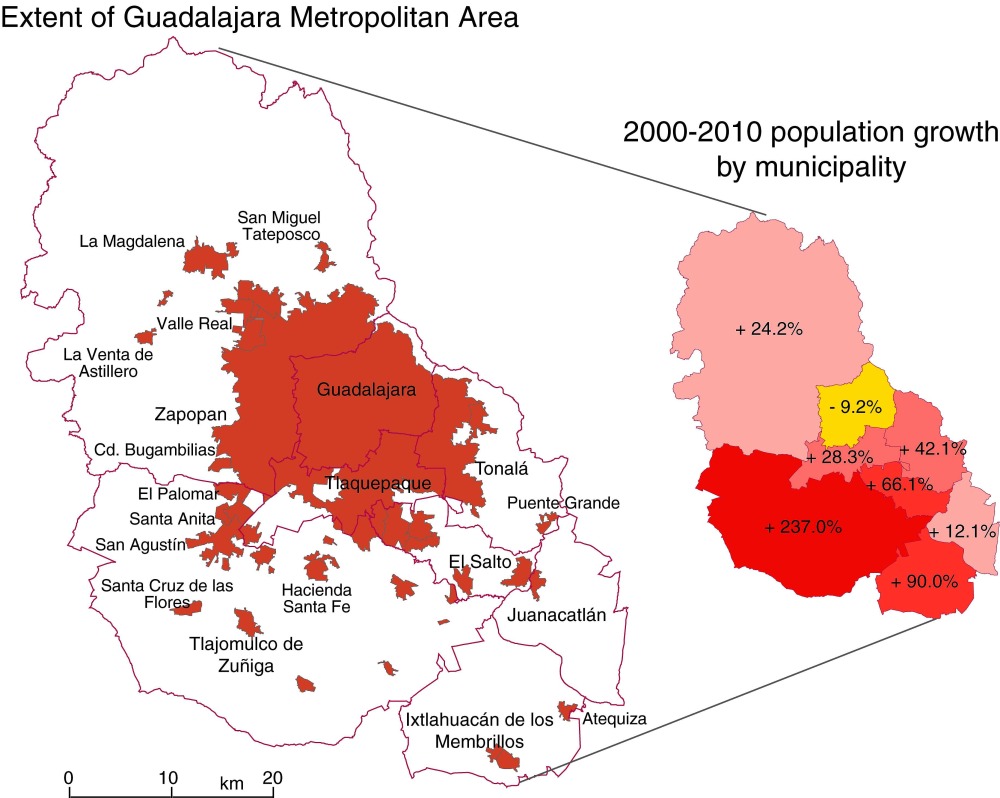

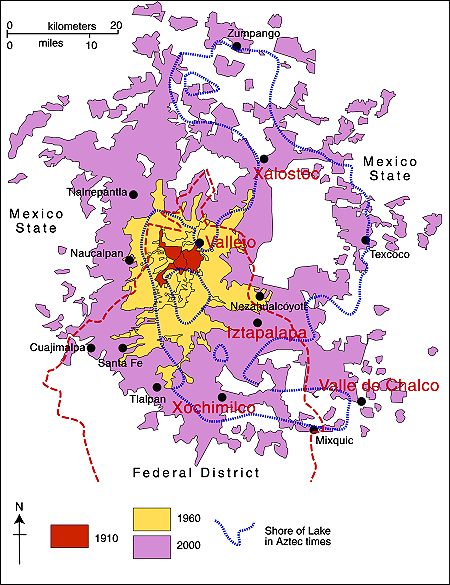

Mexico’s footwear industry is heavily concentrated in three main locations. Manufacturing is focused on the city of León in the state of Guanajuato. Factories and workshops in León account for about 68% of all shoes made in Mexico. The two other important manufacturing areas for footwear are Guadalajara (Jalisco) where about 18% of the national production originates, and Mexico City (together with surrounding parts of the State of Mexico), responsible for 12%.

How has this concentration come about?

León, in Guanajuato, is the center of one of the world’s most complete leather and footwear clusters. The area is a leading supplier and exporter of footwear, saddles and hats.

Footwear has been made in Guanajuato since 1645. The earliest association of shoe makers dates back to 1808. The sector is dominated today by firms with majority Mexican capital. Several of the foreign firms which manufactured shoes here prior to the second world war, changed the focus of their production lines in the early 1940s to specialize in supplying military footwear, leaving the making of consumer footwear to firms with national capital.

Concentration of shoe industry in Mexico.

The advantages of concentration

1. Local raw materials. Local inputs of leather and synthetics reduce the transportation costs (and time) for obtaining raw materials

2. Shared suppliers. Supporting the leather and footwear firms are local suppliers which offer machinery and equipment for tanneries, chemicals, leathers and skins, synthetic materials, dyes and textiles, as well as more specialized shoe-related items such as lasts, soles and heels, accessories and fittings. Shared information and machinery Because the shoe firms are grouped together in a cluster, ideas and information and even specialized machinery can all be shared.

3. Labor. This area has long specialized in footwear and leather products, so all firms benefit from the skilled local labor force.

4. Linkages. Both vertical and horizontal linkages between companies are important in the shoe industry. Vertical linkages occur when one company controls many or all stages in the production line. For instance, a company may make its own accessories and fittings to attach to the shoes it makes, or it may tan its own leather. Horizontal linkages exist where one company is supplied with components (heels, soles) made by another company.

5. Economies of scale.

6. Educational infrastructure. The León area has a variety of educational, training and research centers all supporting the leather and footwear sector. This increases the chances of technological innovations, and the speed of their adoption.

The major advantages of León as an industrial location:

The position of León is key to its success. It is located in central Mexico, close to the major urban areas of Mexico City, Querétaro and Guadalajara. On a broader scale, it is close to the major export markets of the USA, Canada and Central America.

Market proximity is enhanced by an excellent communications network, including good road and rail links, easy access to several major airports, and to seaports such as Manzanillo.

The basic statistics (2009-2010):

- Number of footwear-related firms: about 8000, half of them in Guanajuato.

- Size of firms: 56% micro (fewer than 10 employees), 33% small (10-50 employees).

- Employment: the footwear sector provides 140,000 direct jobs, and twice as many indirect jobs, for a total of 420,000.

- Mexico’s largest shoe maker: Emyco, whose 4,500 workers make 6 million pairs of shoes, boots and sandals (various brands) every year. This firm alone introduces 100 new models every three months.

- Production volume: 250 million pairs/yr, about 1.6% of world total.

- Domestic market: 285 million pairs/yr (average of 2.5 pairs/person/yr)

The domestic market is focused on low-cost shoes, with a few exceptions, such as the market for “cowboy” boots. The manufacture of hand-crafted, high-priced cowboy boots is dominated by smaller firms such as Botas Je-Ver, Botas Jaca and Rancho-Boots, each of which employs 50-200 workers. Some cowboy boots are made from exotic hides, such as crocodile, cayman, armadillo, iguana, ostrich and snake. They are a much-prized status symbol among the upper echelons of Mexico’s drug cartels!

In future posts, we will examine Mexico’s imports and exports of shoes, and see if it is possible to identify any patterns to the distribution of shoe retailers in some of Mexico’s major cities.

Source of statistics: CICEG (Guanajuato Shoe Manufacturers Association) Situación de la industria del calzado en México.

Related posts:

Mexico’s economic geography is analyzed in chapters 14–20 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico. Buy your copy of this invaluable reference guide today!