William H. Beezley, a professor of history at the University of Arizona, has written widely about Mexican history. He was co-editor, alongside Michael C. Meyer, of the Oxford History of Mexico, an illustrated “narrative chronicle” through the centuries, and a landmark modern history of Mexico. In this book, first published in 2008, Beezley explores the development of Mexican National Identity through a history of some facets of its popular culture.

As in the case of his earlier work (Judas at the Jockey Club and Other Episodes of Porfirian Mexico), Beezley’s Mexican National Identity. Memory, innuendo and popular culture (University of Arizona Press), is wide-ranging and engaging. The book consists of five essays on different themes which Beezley considers central to the development of Mexican National Identity.

In the first chapter, Beezley looks at how the character known as El Negrito came to be “one of the most famous marionettes of nineteenth-century puppet theater”. El Negrito, an Afro-American usually portrayed as a Veracruz cowboy, personified the attitudes of nationalistic Mexicans in the nineteenth century, with his mocking of the French and Maximilian, his temper tantrums, his infidelity, his wit and his resistance to the American invaders.

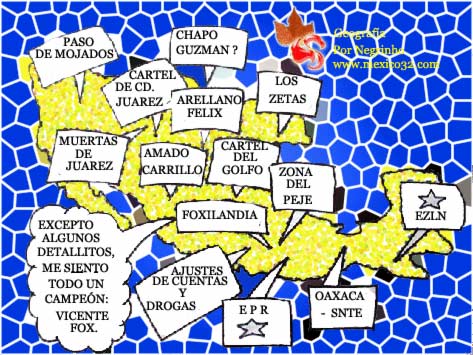

From a geographic perspective, chapter two is the book’s most interesting. The chapter opens by looking at the development of maps which “like symbolic physical features and regional individuals, portrayed Mexico with diversity as the salient attitude”. He describes two 18th century maps, drawn specifically for clerical travelers, highlighting altitude (and therefore climate) and language (ethnicity), but lacking scales, physical features or other landmarks. The modern era of Mexican map-making began with Alexander von Humboldt, and was extended later in the 19th century by others including Antonio García Cubas.

From a geographic perspective, chapter two is the book’s most interesting. The chapter opens by looking at the development of maps which “like symbolic physical features and regional individuals, portrayed Mexico with diversity as the salient attitude”. He describes two 18th century maps, drawn specifically for clerical travelers, highlighting altitude (and therefore climate) and language (ethnicity), but lacking scales, physical features or other landmarks. The modern era of Mexican map-making began with Alexander von Humboldt, and was extended later in the 19th century by others including Antonio García Cubas.

The production of maps necessarily included decisions as to which landmarks, places and features were most important. It also prompted clearer definitions of national boundaries, in both the north and south. In Beezley’s words, “This question of borders had political significance, and both cultural and social dimensions as Mexicans believed the boundaries divided their civilized society from the barbarians beyond.”

Chapter 2 then examines the role of almanacs and lotería (lottery cards), the quintessential Mexican parlor game, in helping to foment national attitudes. Almanacs were “a source of popular or local history and collective memory”. They gave potted summaries of the lives of the saints and martyrs, lists of holy days, images and biographies of political leaders and so on.

Lottery cards shared stereotypical views of objects and characters, often related to local stories. Beezley says that the version played in Campeche eventually gained the greatest popularity. The images used in Campeche formed the basis for the earliest commercially produced sets of cards when Clemente Jacques (a French immigrant and founder of the eponymous food processing brand) first launched his range of culinary products, from chiles, olive oil and mole sauce to beans, jams and honey, and founded his own printing business to print his own labels. Jacques promoted his brand at the world’s fairs in Chicago (1893) and St. Louis (1904), using printed decks of lotería cards as a form of advertising. His cards became the basis for the modern packs of lotería cards sold throughout Mexico. Many of the most common images have multiple associations, some even including an overtly sexual double meaning. Some figures such as El Borracho (The Drunk) and El Valiente (The Brave One) and La Sirena (The Siren/adultery) are not associated with a particular region or place. Others such as The Scorpion and The Toad are readily associated with specific geographic regions or states: Durango and Guanajuato respectively. Almanacs and lotería cards helped reinforce a sense of national identity while recognizing regional and ethnic differences.

In Chapter 3, Beezley focuses on how celebrations of Mexican Independence gradually came to assume a massive significance for national identity. Independence came in 1821, but it was not until 1869 that annual celebrations of Independence Day really took off. On September 16, 1869, the Mexico City-Puebla railway line was inaugurated, beginning an exciting new era for transportation, which was to have far-reaching effects. During the presidency of Porfirio Díaz, Mexico celebrated its centenary of Independence, an event marked with banquets, parades and the opening to the public of a hastily-restored section of “The Pyramids” at the archaeological site of Teotihuacan. Beezley outlines how the popular perception of Mexico’s patron saint, the Virgin of Guadalupe, changed in less than a century from “the terrifying emblem of Padre Miguel Hidalgo’s insurrection, and the patron of downtrodden, rebellious Mexicans, to the patron saint of the dictatorship’s elite.”

Chapter 4 looks at the role of itinerant puppet theater in molding Mexico’s national identity. The largest and most famous single troupe was the Rosete Aranda troupe, formed by two Italian immigrants in 1850. The troupes went from strength to strength in the next half-century. By 1880, the Rosete Aranda company had 1,300 marionettes and by 1900 a staggering 5,104. Their creativity knew few bounds, and by undertaking annual tours around the country, they helped influence opinions and attitudes. Incidentally, their need to undertake annual tours was in keeping with the established principles of central place theory. As described in Geo-Mexico, the same principles apply in the case of traveling circuses.

In the hierarchy of central places, each step up sees a smaller number of places, each providing a wider range of goods and services, and serving a larger market area. This occurs because for a service to be provided efficiently there must be sufficient threshold demand in the central place and its surrounding hinterland to support it. For this reason we do not find new car dealers, heart surgeons or ballet schools in every small village. These activities can only survive in much larger centers where there is sufficient demand. Individual residents are not prepared to travel far in order to access a service of relatively low value. This poses a challenge for services such as puppet shows which are unable to command a high ticket price, but which need large numbers of potential viewers (a large threshold population) if they are to succeed. This quandary can be resolved by moving from one mid-sized center to another throughout the year, gaining access to a new audience in every location.

Needless to say, the invention of modern communications systems such as television means that this is no longer entirely true, except for live performances.

Beezley’s entertaining romp through Mexican popular culture and its links to national identity is well worth reading. It may not discuss all aspects of how Mexico’s national identity developed during the 19th century, but it provides numerous valuable insights into how a country of such diversity gradually acquired a clearer sense of national identity and purpose.

Where to buy:

Mexican National Identity. Memory, innuendo and popular culture, by William H. Beezley (link is to Sombrero Books’ amazon.com page).

While most people may not be familiar with Grupo Bimbo as a corporation, virtually everyone in the Americas at one time or another has consumed Bimbo products. The company makes over 7,000 different products using various brand names, including Sara Lee; Thomas’ English Muffins; Entenmann’s pastries; Arnold’s, Orowheat, Mrs. Baird’s, Wonder (in Mexico only); Freihofer’s; Stroehmann’s; Brownberry; Old Country; Milpa Real and Tia Rosa (tortillas and related products); Barcel (chips and salted snacks; Marinela (sweet snacks); Boboli (pizza crusts); Coronado (cajeta) and El Globo fancy pastry and coffee shops.

While most people may not be familiar with Grupo Bimbo as a corporation, virtually everyone in the Americas at one time or another has consumed Bimbo products. The company makes over 7,000 different products using various brand names, including Sara Lee; Thomas’ English Muffins; Entenmann’s pastries; Arnold’s, Orowheat, Mrs. Baird’s, Wonder (in Mexico only); Freihofer’s; Stroehmann’s; Brownberry; Old Country; Milpa Real and Tia Rosa (tortillas and related products); Barcel (chips and salted snacks; Marinela (sweet snacks); Boboli (pizza crusts); Coronado (cajeta) and El Globo fancy pastry and coffee shops.

Jacques Cousteau

Jacques Cousteau