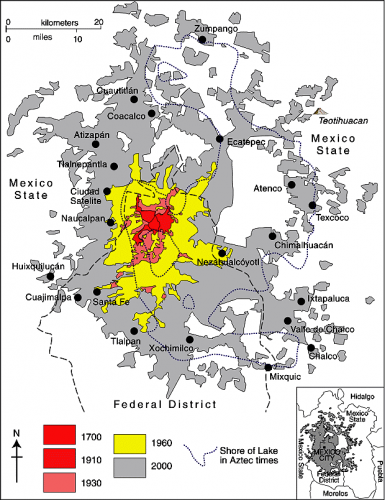

Mexico City is one of the world’s largest cities, and the metropolitan area of Greater Mexico City (map) extends well beyond the borders of the Federal District (Mexico City proper) into neighboring states, especially the State of Mexico. The total population of Greater Mexico City is about 22 million, all of whom need safe access to water.

An old joke relates how engineers initially rejoiced at successfully draining the former lake on which Mexico City was built (something the Aztecs had tried, but failed to achieve), only to discover that the city now lacked any reliable source of fresh water for its inhabitants (something the Aztecs had successfully managed by building a system of aqueducts). Water has been a major issue for Mexico City ever since it was founded almost 700 years ago.

The Mexico City Metropolitan Area’s water supply is currently calculated to be around 82 m³/s. (The precise figure is unclear because many wells are reportedly unregistered). The main sources of water (and their approximate contributions to total water supply) are:

- Abstraction of groundwater (73%)

- Cutzamala system (18%)

- Lerma system (6%)

- Rivers and springs (3%)

In several previous posts we have looked at several issues arising from groundwater abstraction:

- How fast is the ground sinking in Mexico City and what can be done about it?

- Why are some parts of Mexico City sinking into the old lakebed?

- More ground cracks appearing in Mexico City and the Valley of Mexico

- Subsidence incident leads to demolition of 31 homes in the State of Mexico

- The challenge of building and maintaining Mexico City’s metro system

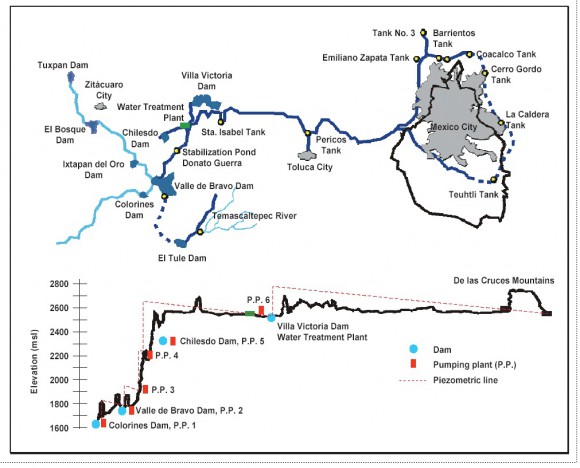

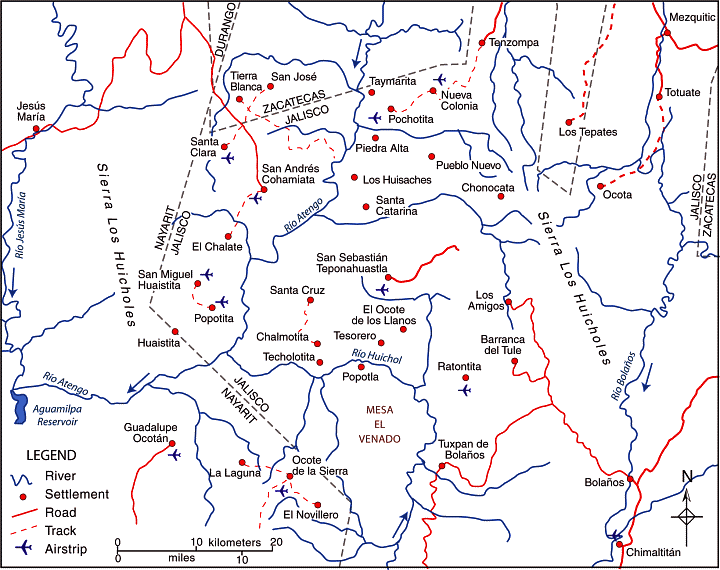

In this post we focus on the Cutzamala system (see graphic), one of Mexico’s most ambitious engineering feats of its time.

The Cutzamala system supplies potable water to 11 boroughs (delegaciones) of the Federal District and 11 municipalities in the State of Mexico. The Cutzamala system is one of the largest water supply systems in the world, in terms of both the total quantity of water supplied (about 485 million cubic meters/yr) and in terms of the 1100 meters (3600 feet) difference in elevation that has to be overcome. The system cost about $1.3 billion, and was undertaken in three successive phases of construction, completed in 1982 (Villa Victoria dam), 1985 (incorporation of the Valle de Bravo and El Bosque dams, originally built in the 1940s and 1950s) and 1993 respectively.

As Cecillia Tortajada points out in Who Has Access to Water? Case Study of Mexico City Metropolitan Area, the investment of $1.3 billion was, at the time (1996), “higher than the national investment in the entire public sector in Mexico… in the areas of education ($700 million), health and social security ($400 million), agriculture, livestock and rural development ($105 million), tourism ($50 million), and marine sector ($60 million).”

The system includes 7 dams and reservoirs for storage, 6 major pumping stations (P.P. on the graphic) and a water purification plant. The volumes stored in the system are dependent on previous years’ rainfall. Water is transferred to the Valley of Mexico from more than 150 km away via reservoirs, pumping stations, open channels, tunnels, pipelines and aqueducts.

The Cutzamala system incorporates the Valle de Bravo and El Bosque dams, built originally as part of the “Miguel Alemán” project that generated hydro-electric power from the headwaters of the Cutzamala River (hence the name for the whole system). The reservoir at Valle de Bravo is an important resource for tourism and watersports. The hydro-electric power scheme is no longer functioning. The Cutzamala system has the capacity to supply up to 19 m³/s of water to the Valley of Mexico. In practice, it supplies almost 20% of the Valley of Mexico’s total water supply (usually quoted as being 82 m³/s).

The pumping required to lift water 1100 meters from the lowest storage point to the system’s highest point (from where gravity flow takes over) consumes a significant amount of energy, variously estimated at between 1.3 and 1.8 terawatt hours a year, equivalent to about 0.6% of Mexico’s total energy consumption, and representing a cost of about 65 million dollars/yr. This amount of electricity is claimed to be roughly equivalent to the annual energy consumption of the metropolitan area of Puebla (population 2.7 million).

The total operational costs for running the Cutzamala System are estimated at $130 million/yr. [all figures in US dollars]. Even operating at full capacity (19 m³/s or 600 million m³/yr), the approximate average cost of water would be $0.214/m³. The true costs are higher given that these calculations do not include the costs of treatment or distribution within the metropolitan area. The price charged to consumers averages about $0.20/m³.

The completion of the Cutzamala system involved resettling some villages. The plans included the construction of some 200 “social” projects to improve living conditions for the people most affected, including local potable water distribution systems, schools and roads. However, more than a decade after completion, there were still some unresolved conflicts concerning people forced to move, with many of them still claiming that they had received insufficient compensation.

Maintaining the Cutzamala system has been an on-going challenge. Most maintenance is scheduled for the Easter holiday period, when factories and offices close down and many Mexico City residents head for the beach, reducing demand for water. Since 1993, a parallel system of canals and pipelines has been built alongside the original system, allowing for sections of the old system to be shut down for maintenance, obviating the need to close the entire system whenever work is carried out.

Main sources:

- Cecilia Tortajada. 2006. Who Has Access to Water? Case Study of Mexico City Metropolitan Area [pdf file]. Human Development Report Office Occasional Paper.

- Overview of the Infrastructure for Cutzamala System. Source: IMTA, 1987, Visita al Sistema Cutzamala. Boletín No. 2. Instituto Mexicano de Tecnología del Agua, México.

Related posts:

- How fast is the ground sinking in Mexico City and what can be done about it?

- Maintaining the drains and sewers of Mexico City

- Mexico D.F. administration offers amnesty to illegal water users

- Which cities have the best and worst water systems in Mexico?

- Mexico’s freshwater aquifers: undervalued and overexploited

- Mexico’s major cities confront serious water supply issues