There is a close connection between geology and relief in many parts of Mexico. In this post we describe a one-day fieldwork excursion in the Tequisquiapan area of the central state of Querétaro that looks at this connection. The fieldwork is suitable for high school students but could easily be extended to provide challenges for college/university students.

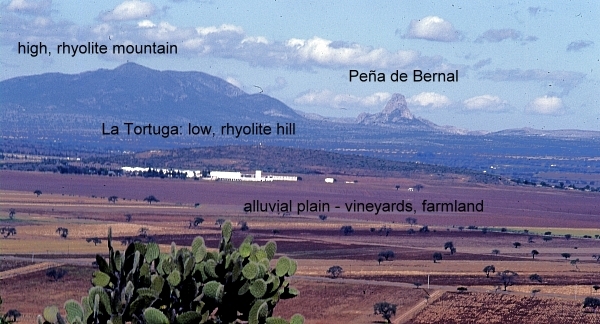

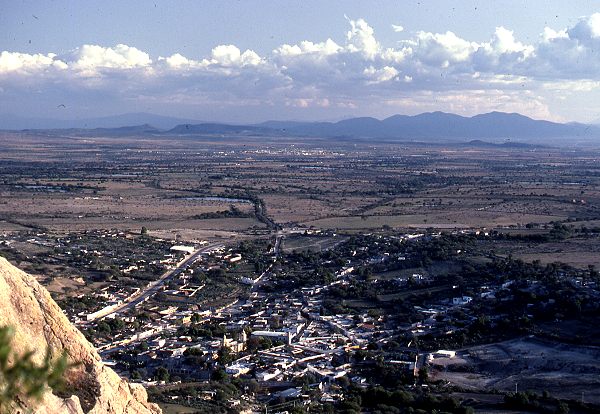

The fieldwork starts with a fieldsketch from near Tequisquiapan. Any suitable vantage point will do, provided it offers a clear view northwards to the very distinctive Peña de Bernal (seen in the background of the photo below). At this point, a simple line sketch should suffice to help students identify the following four different kinds of terrain:

- flat or gently sloping plain, used for cultivation

- low hills, with gently sloping sides, which look to be covered in bushes and cacti [scrub vegetation]

- high mountains, with steeper slopes, also with no obvious signs of cultivation

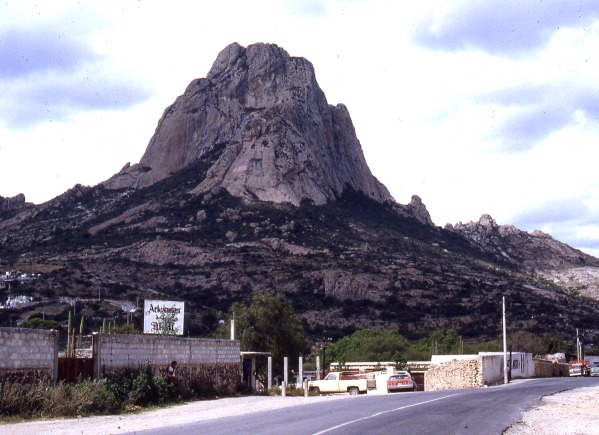

- the Peña de Bernal itself, a distinctive monolith with exceptionally steep sides

There is no need to identify any rocks or use any geological terms (students can add appropriate labels later!). Engage the students in a discussion about why there might be four different kinds of relief visible in this area, and how their ideas or hypotheses could be investigated further. Conclude the discussion by explaining that they are now going to look for evidence related to the idea that these four different kinds of relief are connected to significant differences in geology.

The next stop is a small roadside quarry on the flat area. The most accessible quarry many years ago was located a short distance south of Tequisquiapan on the east side of the highway, but any quarry on the flat land will serve to reveal the rocks that form the plain.

[Warning: Ensure that you park off the highway; when examining the rock in the quarry, avoid any overhanging sections, and do not do anything to cause slope instability or collapse].

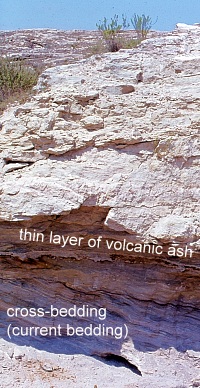

The rocks in the quarry are in layers (sedimentary) and very distinctive. The individual particles of the rock are rough to the touch and sand-sized, so this is some kind of sandstone.

Some layers are more or less horizontal, but in places successive layers are laid down at a much steeper angle. This is “current bedding” and indicates that the rocks were formed by water, perhaps where a river entered a lake. The individual particles in the rock are not well-rounded, so have not traveled all that far.

Within each major layer, the material shows signs of sorting, with fine material sitting on top of coarse material. In some places, the sandstone contains small pebbles, so this rock is a sandstone conglomerate. Small casts of fossil shells can be seen in places, further suggesting it is a sedimentary rock deposited in a former lake.

A very thin white layer is present (at about head height in the photo). This layer is totally different to the sandstone conglomerate. It is fine material that has been compacted. Given the volcanic history of central Mexico, this is almost certainly a thin layer of volcanic ash that covered older rocks before being covered in turn by the next layer of sediments.

With some guidance, students should be able to work most of this out for themselves! The last stage at this stop is to ask why this rock forms the flat land in the area, rather than the hills. (Answer: softer, weaker, less resistant, easier to erode, etc).

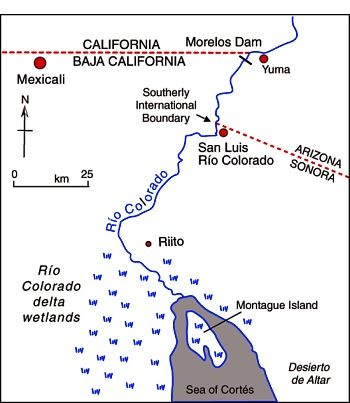

The next stop is to take a look at the rock forming the low hills. The highway between Tequisquiapan and Ezequiel Montes (see map) conveniently cuts through a low ridge at San Agustín. This affords an opportunity to take a close look at the rock forming that ridge. [Warning: Ensure that you find a safe parking spot, and take every precaution, since traffic along this highway can be heavy and very fast-moving]

The rock at San Agustín is darker and much harder than the rock in the quarry. It has clear crystals in it, apparently arranged haphazardly. From its color (grey) and grainsize (fine), it is a rhyolite [a fine grained, acid igneous rock]. It is far more difficult to erode than the sandstone on the plain, so it forms upstanding ridges and low hills in the landscape.

From San Agustín, drive through Ezequiel Montes and on to the town of Bernal, one of Mexico’s “Magic Towns“. The next part is the most physically-challenging part of the excursion since it is necessary to climb at least part-way up the Peña de Bernal! [Warning: this is very steep in places, and climbing beyond the mid-way “chapel” is definitely not recommended]. Examining the rocks of the Peña de Bernal reveals that they are lighter in color than the rhyolite and fine-grained, but with larger crystals (phenocrysts) in some places. This rock must have cooled very slowly (or the phenocrysts would not have had chance to form) and this is an intrusive igneous rock known as microgranite. Eagle-eyed students should also find some other rocks while climbing the Peña de Bernal. In places, it is possible to find good specimens of a very hard, banded metamorphic rock that was formed when heat and/or pressure transformed pre-existing rocks. The banded rock is a gneiss [pronounced “nice”].

The presence of intrusive igneous rocks (formed underground) together with metamorphic rocks strongly suggest that the Peña de Bernal is an example of a volcanic plug. It represents the central part (and all that now remains) of a former volcano, whose sides, presumably composed of ashes and lava, have long since eroded away.

Conclusion:

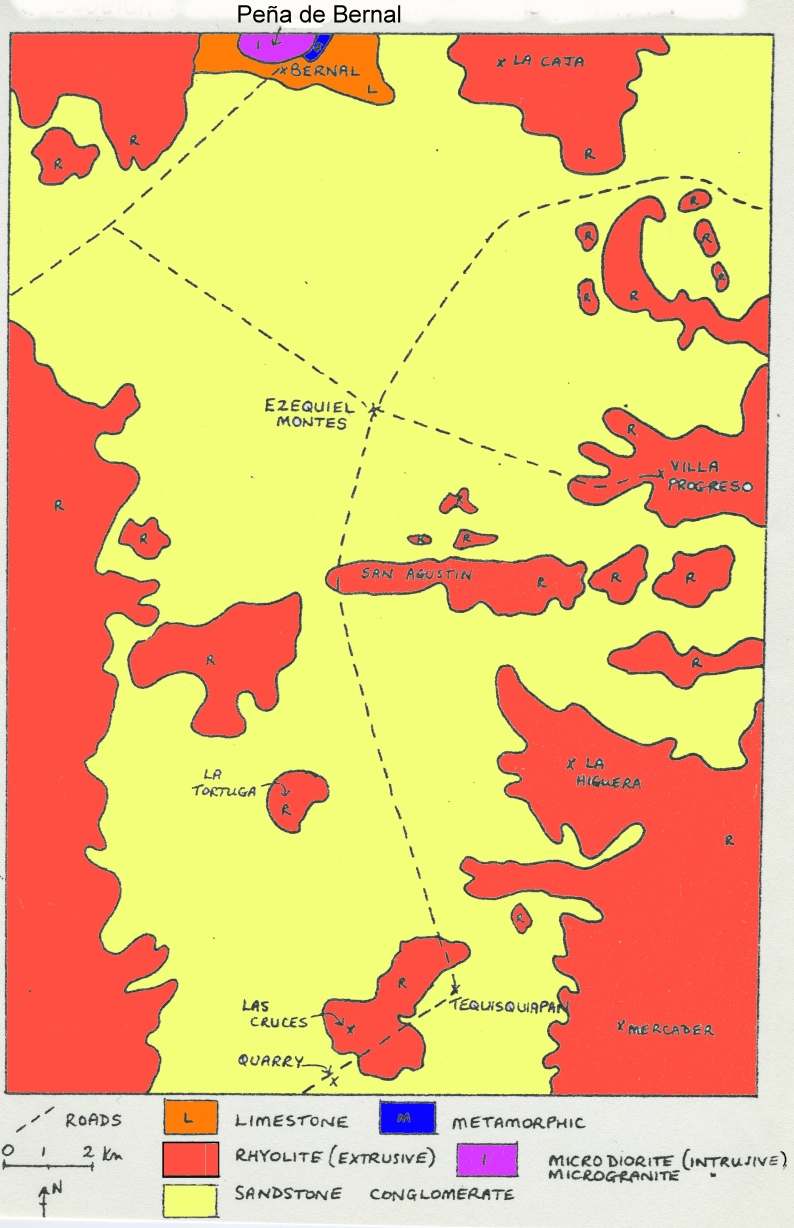

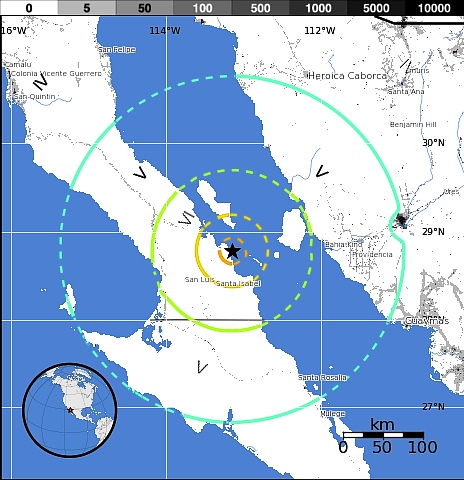

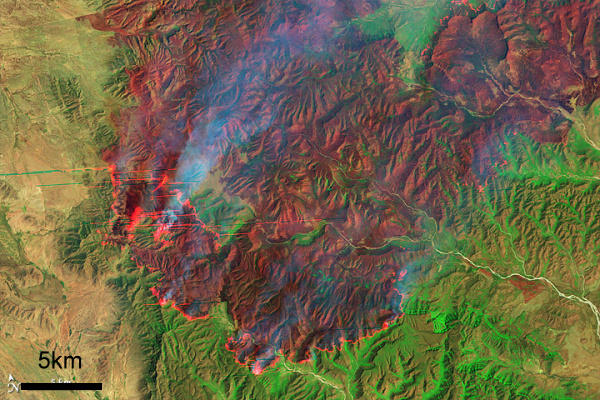

After students have had chance to work most of this out for themselves, a look at the local geological map should confirm that their deductions are reasonable. As can be seen on the map below, the flat area is indeed an alluvial plain (sandstone), with low rhyolite hills and ridges in places, and higher rhyolite mountains in the background, with the distinctive Peña de Bernal made of igneous and metamorphic rocks at the northern edge of the map.

In this particular part of Mexico, as in many other areas, the link between geology and relief is very strong! Happy exploring!

Related posts: