After the conquest, Spanish settlers introduced numerous Old World species into the New World. The most pernicious introductions were human-borne diseases, which led to the rapid and tragic decimation of the indigenous population. However, most of the introductions were deliberate, made with the intention of increasing the diversity of available food and resources. Among the non-native (exotic) plants and animals introduced were sheep, pigs, chickens, goats, cattle, wheat, barley, figs, grapevines, olives, peaches, quinces, pomegranates, cabbages, lettuces and radishes, as well as many flowers.

The environmental impact of all these introductions was enormous. The introduction of sheep to Mexico is a case in point.

In the Old World, wool had been a major item of trade in Spain for several centuries before the New World was settled. The first conquistadors were quick to recognize the potential that the new territories held for large-scale sheep farming.

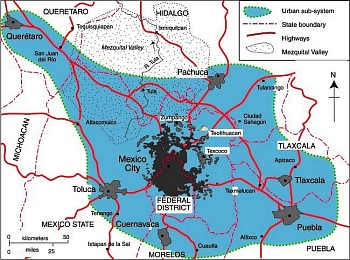

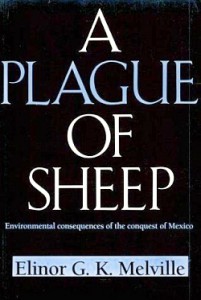

The development of sheep farming and its consequences in one area of central Mexico (the Valle de Mezquital in Hidalgo) was analyzed by Elinor Melville in A Plague of Sheep. Environmental Consequences of the Conquest of Mexico.

The development of sheep farming and its consequences in one area of central Mexico (the Valle de Mezquital in Hidalgo) was analyzed by Elinor Melville in A Plague of Sheep. Environmental Consequences of the Conquest of Mexico.

Melville divides the development of sheep farming in the Valle of Mezquital into several distinct phases. Sheep farming took off during Phase I (Expansion; 1530-1565). During this phase, the growth in numbers of sheep in the region was so rapid that it caused the enlightened Viceroy, Luis de Velasco, to became concerned that sheep might threaten Indian land rights and food production. Among the regulations introduced to control sheep farming was a ban on grazing animals within close proximity of any Indian village. At first the Indians did not own any grazing animals, and consequently did not fence their fields, which inadvertently encouraged the Spaniards to treat the landscape as common land.

During Phase II (Consolidation of Pastoralism; 1565-1580), the area used for sheep grazing remained fairly stable, but the numbers of sheep (and therefore grazing density) continued to increase. By the mid-1570s, sheep dominated the regional landscape and the Indians also had flocks. One of the consequences of this was environmental deterioration to the point where by the late 1570s, some farmers did not have adequate year-round access to pastures and introduced the practice of seasonal grazing in which they moved their flocks (often numbering tens of thousands of sheep) from their home farm in central Mexico to seasonal pastures near Lake Chapala.

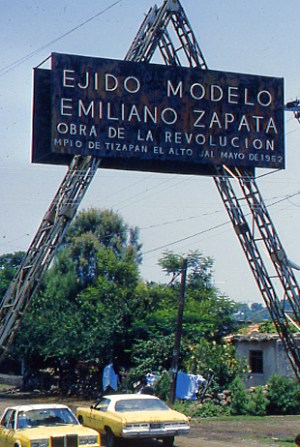

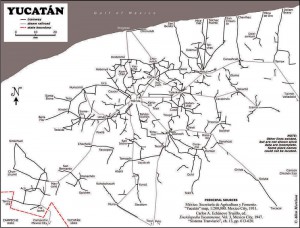

This practice of grazing on harvested fields or temporary pastures was known as agostadero. This term originally applied to summer (agosto=August) grazing in Spain but was adopted in New Spain for “dry season” grazing, between December and March. So important was this annual movement of sheep that provision was made in 1574 for the opening of special sheep lanes or cañadas along the route, notwithstanding the considerable environmental damage done by the large migrating flocks. As flock sizes peaked, more than 200,000 sheep made the annual migration by 1579.

In the words of historian Francois Chevalier:

By 1579, and doubtless before, more than 200,000 sheep from the Querétaro region covered every September the 300 or 400 kilometers to the green meadows of Lake Chapala and the western part of Michoacán; the following May, they would return to their estancias.

The prime dry season pastures were those bordering the flat, marshy swampland at the eastern end of Lake Chapala. The Jiquilpan district alone supported more than 80,000 sheep each year, as the Geographic Account of Xiquilpan and District (1579) makes clear:

More than eighty thousand sheep come from other parts to pasture seasonally on the edge of this village each year; it is very good land for them and they put on weight very well, since there are some saltpeter deposits around the marsh.

By the end of Phase III (The Final Takeover; 1580-1600), most land had been incorporated into the Spanish land tenure system, the Indian population had declined (mainly due to disease) and the sheep population had also dropped dramatically. Contemporary Spanish accounts reveal that this collapse was attributed to a combination of the killing of too many animals for just their hides by Spaniards, an excessive consumption by Indians of lamb and mutton, and by the depletion of sheep flocks by thieves and wild dogs. Melville’s research, however, suggests that the main reason for the decline was actually environmental degradation, brought on by the excessive numbers of sheep at an earlier time.

The entire process is, in Melville’s view, an excellent example of an “ungulate irruption, compounded by human activity.” The introduction of sheep had placed great pressure on the land. Their numbers had risen rapidly, but then crashed as the carrying capacity of the land was exceeded. The carrying capacity had been reduced as (over)grazing permanently changed the local environmental conditions.

By the 1620s, the serious collapse in sheep numbers in the Valle de Mezquital was over; sheep farming never fully recovered. The landscape had been changed for ever.

Sources / Further reading:

- Acuña, R. (ed) Relaciones geográficas del siglo XVI: Michoacán. Edición de René Acuña. Volume 9 of Relaciones geográficas del siglo XVI. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. 1987

- Chevalier, F. Land and Society in Colonial Mexico. University of California Press. 1963.

- Melville, Elinor G. K. A plague of Sheep. Environmental consequences of the conquest of Mexico. Cambridge University Press. 1994.

Click here for the original article on MexConnect.

Mexico’s ecosystems and biodiversity are discussed in chapter 5 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico. The concept of carrying capacity is analyzed in chapter 19. Buy your copy today, as a useful reference book!