By common consent, the history of blacks in what-is-now Mexico is a long one. The first black slave to set foot in Mexico is thought to have been Juan Cortés. He accompanied the conquistadors in 1519. It has been claimed that some natives thought he must be a god, since they had never seen a black man before.

A few years later, six blacks are believed to have taken part in the successful siege of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan. Several hundred other blacks formed part of the wandering, fighting forces employed in the name of the Spanish crown to secure other parts of New Spain.[1]

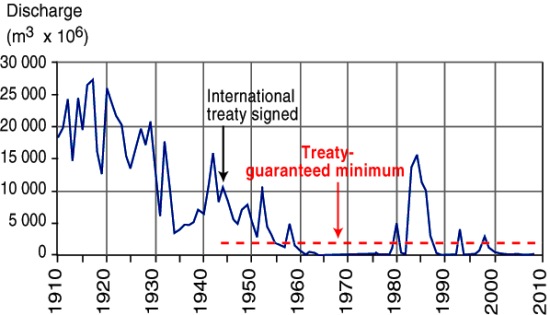

The indigenous population crashed in the first hundred years following the conquest, largely as a result of smallpox and other European diseases. Estimates of the native population prior to the conquest range from 4 to 30 million. A century later, there were just 1.6 million.

New Spain had been conquered by a ludicrously small number of Spaniards. To retain control and in order to begin exploiting the potential riches of the virgin territory they had won, a good supply of laborers was essential. There were not enough locals, so imports of slaves became a high priority.

New Spain had been conquered by a ludicrously small number of Spaniards. To retain control and in order to begin exploiting the potential riches of the virgin territory they had won, a good supply of laborers was essential. There were not enough locals, so imports of slaves became a high priority.

By 1570, almost 35% of all the mine workers in the largest mines of Zacatecas and neighboring locations were African slaves. [2] Large numbers of slaves were also imported for the sugar plantations and factories in areas along the Gulf coast, such as Veracruz. By the mid-seventeenth century, some 8,000-10,000 blacks were Gulf coast residents. After this time, the slave trade to Mexico gradually diminished.

Miguel Hidalgo, the Independence leader, first demanded an end to slavery in 1810 (the same year that Upper Canada freed all slaves). Slavery was abolished by President Vicente Guerrero on September 15, 1829.

During the succeeding 36 years, prior to the abolition of slavery in the U.S. (1865), some U.S. slaves seized their chance and headed south in search of freedom and opportunity. Recognizing the potential, in 1831, one Mexican senator, Sánchez de Tagle, a signatory of the Act of Independence, called for assistance to be given to any blacks wanting to move south on the grounds that this movement would possibly prevent Mexico being invaded by white Americans. [3] Sánchez de Tagle’s point was that black immigrants would be strong supporters of Mexico since they wouldn’t want to be returned to slavery, and would be preferable to white Americans, who might be seeking an opportunity to annex parts of Mexico for their homeland. Sánchez de Tagle’s fears came to pass. One year after the U.S. annexed the slave-holding Republic of Texas in 1845, it invaded Mexico.

Perhaps as many as 4,000 blacks entered Mexico between 1840 and 1860. At the beginning of 1850, several states enacted a series of land concessions for black immigrants, in order that undeveloped areas with agricultural potential might be settled and farmed.

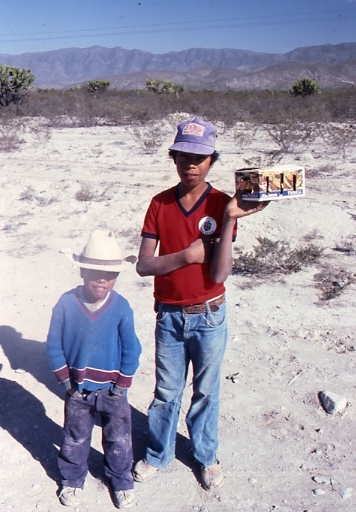

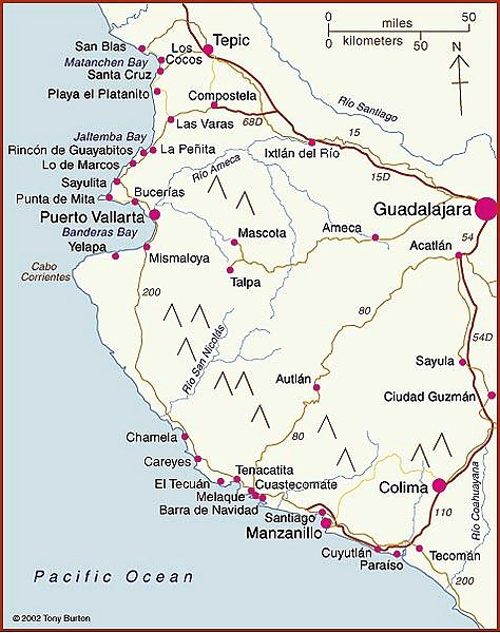

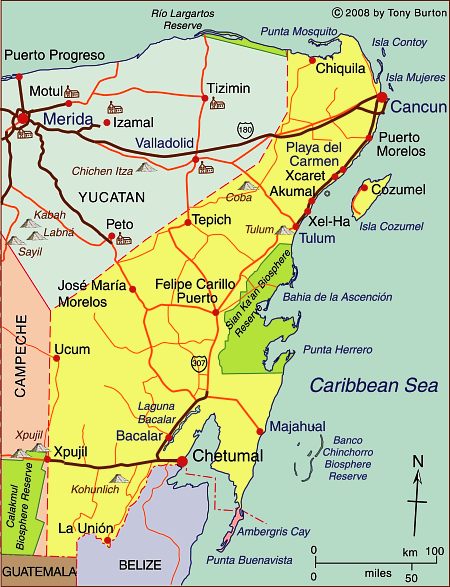

Even after the abolition of slavery in the U.S., small waves of blacks continued to arrive periodically in Mexico. Many came from the Caribbean after 1870 to help build the growing national railway network. In 1882, some 300 Jamaicans arrived to help build the San Luis Potosí-Tampico line; another 300 Jamaicans made the trip in 1905 to take jobs in mines in the state of Durango. [4] Partially as a response to their own independence struggles, thousands of Cubans came after 1895. They favored the tropical coastal lowlands such as Veracruz, Yucatan and parts of Oaxaca, where the climate and landscapes were more familiar to them than the high interior plateaux of central Mexico.

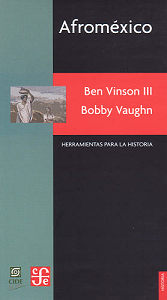

Mexican historians have largely ignored the in-migration of blacks and their gradual intermarriage and assimilation into Mexican society. For a variety of reasons, they chose to focus instead on either the indigenous peoples, or the mestizos who form the majority of Mexicans today. The pendulum is finally beginning to swing back, as researchers like Charles Henry Rowell, Ben Vinson III and Bobby Vaughn re-evaluate the original sources, and examine the life and culture of the communities where many blacks settled.

Most work about the influence of blacks on modern-day Mexico has focused on the Veracruz area, in particular on the settlements of Coyolillo, Alvarado, Mandinga and Tlacotalpan. 5 On the opposite coast, Bobby Vaughn has spent more than a decade studying the Costa Chica of Oaxaca and Guerrero. [6]

Analysts of Mexican population history emphasize the poor reliability of early estimates and censuses, as well as the complex mixing of races which occurred with time. While the precise figures and dates may vary, most demographers appear to agree with Bobby Vaughn that the black population, which rose rapidly to around 20,000 shortly after the conquest, continued to exceed the Spanish population in New Spain until around 1810.

It is estimated that more than 110,000 black slaves (perhaps even as many as 200,000) were brought to New Spain during colonial times. Happily, their legacy is still with us, and lives on in the language, customs and culture of all these areas.

Sources / Further Reading

1 Matthew Restall. Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest. (Oxford University Press) 2003

2 Peter J. Bakewell. Silver Mining and Society in Colonial Mexico: Zacatecas, 1546-1700, cited in Afroméxico.

3 Vinson III, Ben & Vaughn, Bobby. Afroméxico. (in Spanish; translation by Clara García Ayluardo) Mexico: CIDE/CFE. 2004. The main source for this column, divided into three parts. Following a joint introduction, Ben Vinson III, Professor of Latin American History at Penn State University, provides a detailed overview of studies connected to blacks in Mexico. Then Bobby Vaughn, who has a doctorate in anthropology from Stanford University, adopts an ethnographic perspective in writing about the Costa Chica of Oaxaca and Guerrero; his short essay includes discussion of the Black Mexico movement. The work concludes with an extensive bibliography of sources relating to Afroméxico.

4 Vinson III, Ben & Vaughn, Bobby. Afroméxico. Mexico: CIDE/CFE. 2004

5 See, for example, the Winter 2004 and Spring 2006 issues of Callaloo (A Journal of African Diaspora Arts and Letters). The Spring 2006 issue, vol 29, #2, pp 397-543, has a series of articles under the general heading of “Africa in Mexico”, including transcriptions of fascinating interviews with such characters as Rodolfo Figueroa Martinez, who relates the history of how several local towns, including San Lorenzo de los Negros (now Yanga) were founded by blacks, and of how a black identity gradually emerged. Other interviewees discuss how they view their color and Afromestizo identity, lamenting the fact that their history has been distorted or largely forgotten. Local food and festival celebrations are also highlighted.

6 Bobby Vaughn’s Black Mexico Home Page, Afro-Mexicans of the Costa Chica, available via MexConnect, provides links to several of his articles including Blacks in Mexico. A Brief Overview.

Original article on MexConnect