In north-western Mexico, two towns in close proximity—Los Mochis and Topolobampo—are both examples of “new towns”. Many Mexican towns and cities are more than 500 years old; relatively few major settlements in the country are less than 150 years old. How did it come about then that these two “new towns” in the state of Sinaloa were founded so close to one another?

Topolobampo dates back only as far as 1872, when a US engineer, Albert Kimsey Owen (1847-1916) arrived. Owen envisaged the city as a U.S. colony centered on sugar-cane production in this previously unsettled area and as the terminus for a railway across the Sierra Madre Occidental.

Owen had been raised in New Harmony, the city founded by Robert Owen (no relation) and decided to try and found a similar “ideal socialist” city somewhere in Mexico. In 1871-1872 he visited Chihuahua and Sinaloa and decided that the site of present day Topolobampo was ideal for his purposes. Owen founded the Texas, Topolobampo and Pacific Railroad and Telegraph Company (later the American and Mexican Pacific Railroad) and in 1881 was granted the concession for the settlement of a town.

Settlement began in October 1886. Two and a half years later, in April 1889, the first large group of colonists—300-strong—set sail from New York, arriving in Sinaloa in July, only to find a deserted beach and no Owen. Owen had returned to the USA but finally arrived the following year with another 30 colonists. During 1891, 70 more settlers arrived. They founded several additional settlements including Vegatown (Estación Vega), La Logia, El Público and El Platt. They also dug an irrigation canal, 12 kilometers long, to divert water from the Fuerte River across their lands. Despite their heroic efforts, the farming project was eventually abandoned, though the town of Topolobampo struggled on.

The Henry Madden Library of the California State University, Fresno, houses an amazing visual record of those early years, based on photos dating back to 1889-90 taken by Ira Kneeland, one of the first settlers.

Meanwhile, in 1893, another American, Benjamin Francis Johnston (1865-1937) founded the Eagle Sugar Co. (Compañia Azucarera Aguila S.A.) and constructed a factory, church, airport, dam, and the Memory Hill lighthouse. Ten years later, in 1903, Johnston officially founded Los Mochis. Johnston came to own more than 200,000 hectares. He built a veritable palace of a residence, including an indoor pool and even an elevator, one of the first in the country. The mansion’s garden, full of exotic plants, is now the city’s botanical gardens, Parque Sinaloa. The mansion itself was later torn down for a shopping plaza.

Historians and geographers have long questioned the precise motives of both Owen and Johnston, whose efforts have been described as more akin to capitalist expansion and neo-imperialism than any form of socialism. If they had come to fruition, Owen’s projects could have resulted in the annexation of a million square kilometers to a USA which had ambitious ideas of expansion at the time. Owen has been labeled variously a visionary, a madman or a conman and fraudster. Similarly, Johnston has also been regarded by some as a stooge for grandiose US expansionist plans.

Whatever the motives of their founders, both Topolobampo and Los Mochis had their start and have rarely looked back. Los Mochis gained importance as a major commercial center, marketing much of the produce grown on the enormous El Fuerte irrigation scheme. A large proportion of this produce is exported to the U.S. via the famous Copper Canyon railway. Los Mochis is the passenger terminus at the western end of the line. For freight, the line continues to Topolobampo, “the lion’s watering place” or “tiger’s water”. The port, with its shrimp-packing plant, is at the head of one of Mexico’s finest natural harbors, the head of a drowned river valley or ria, which affords an unusually high degree of security in the event of hurricanes.

This is an edited version of an article originally published on MexConnect. Click here for the original article

Urban settlements in Mexico are discussed in chapters 21 and 22 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico, with urban issues being the focus of chapter 23.

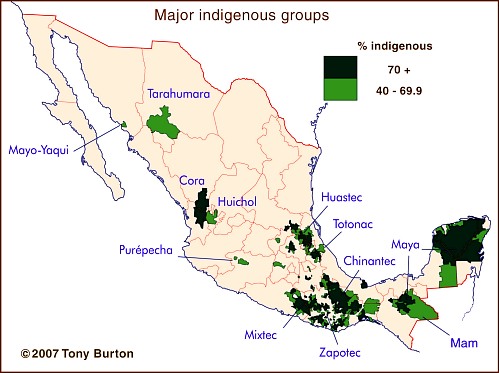

From 1950-1970, the Mexican government opted for a modernization approach, building roads (including the Pan-American highway) and attempting to upgrade agricultural techniques. The mainstay of the regional economy is coffee. During this period, most Mam were peasant farmers, subsisting on corn and potatoes, gaining a meager income by working, at least seasonally, on coffee plantations. Working conditions were deplorable, likened in one report to “concentration camps”. Plantation owners forced many into indebtedness. The Mam refer to this period as the time of the “purple disease”:

From 1950-1970, the Mexican government opted for a modernization approach, building roads (including the Pan-American highway) and attempting to upgrade agricultural techniques. The mainstay of the regional economy is coffee. During this period, most Mam were peasant farmers, subsisting on corn and potatoes, gaining a meager income by working, at least seasonally, on coffee plantations. Working conditions were deplorable, likened in one report to “concentration camps”. Plantation owners forced many into indebtedness. The Mam refer to this period as the time of the “purple disease”: