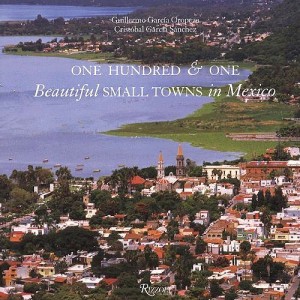

In an earlier post, we listed the towns included in One Hundred and One Beautiful Small Towns in Mexico, by Guillermo García Oropeza and Cristóbal García Sánchez (Rizzoli International Publications, 2008; 280 pp.). Here we offer a short review of the book.

This is a large format book, with many magnificent photographs. A fascinating range of places is included, even though the criteria used for their selection are nowhere explained. The selection offers lots of interest for anyone curious about Mexico’s geography.

This is a large format book, with many magnificent photographs. A fascinating range of places is included, even though the criteria used for their selection are nowhere explained. The selection offers lots of interest for anyone curious about Mexico’s geography.

For example, a stunning aerial view of Mexcaltitán (Nayarit) shows the cross-and-concentric-circle street pattern of “Mexico’s Venice”, surrounded by muddy brown shrimp-bearing swamps.

Curiously, the list of places included in the book on the contents pages adopts the affected style of using no capital letters whatsoever for any of the town names.

Each place is afforded at least a double page spread, and the back of the book has helpful lists of tourist offices, and selected hotels and restaurants.

Despite the title, some of the locations are more to do with the natural environment than with settlement. For instance, the town of Cuatro Ciénegas is a somewhat unprepossessing place whereas the desert oases of Cuatro Ciénegas,on which the book entry focuses, are an amazing natural zoological laboratory of crystalline water and extraordinary biodiversity. Similarly, Cacahuamilpa Caverns hardly qualify as a town!

The San Ignacio entry focuses on difficult to reach cave paintings. The village itself has few claims to fame beyond its colonial mission church.

The Paricutín double-page spread is named after the volcano which devoured several small settlements including Parícutin (for the name of the original village, the accent is on the second syllable; for the volcano it is on the last syllable). The photos included here actually show (as the captions make clear) the towns of Angahuan, and the upper facade of the church of San Juan Parangaricutiro, overwhelmed by the volcano’s lava.

A couple of places are given names that might not be very familiar to their residents. Casas Nuevas (Chihuahua) is actually Nuevo Casas Grandes (the real Casas Nuevas is an entirely different place which had only 13 inhabitants at the time of the 2000 census) and Mineral del Monte (Hidalgo) is more usually known as Real del Monte.

In southern Mexico, Santa María del Tule gets an entry. Santa María would not be worthy of mention, except for the fact that it is home to what is arguably the world’s largest tree, now thankfully restored to good health after decades of neglect.

In the Yucatán, three entries ignore the main thrust of the book, and focus instead on significant routes, one linking henequen (sisal) haciendas, one combining relatively minor archaeological sites which share distinctive Puuc architecture, and one going from one friary (monastery) to another. These are all interesting trips, but are entirely unexpected in a book specifically about towns. Some judicious editing might have removed some of the inaccuracies such as describing hemp (sisal) as “in the agave… or cactus, family”. The family name for agaves is Agavaceae which includes the genus Agave. In any event, agaves are biologically distinct to all members of the Cactaceae family; confusing agaves with cacti is an unexpected blunder.

The chosen towns quite rightly include some long-abandoned sites such as Teotihuacan, “City of the Gods”, which was once a city of 200,000 or so, the fascinating Mayan sites of Palenque and Chichen Itza, and Mitla and Monte Alban, both in Oaxaca.

The cover photo of the town of Chapala in Jalisco, much favored by American and Canadian retirees in recent years, unfortunately dates from a time when the lake level was relatively low. The green areas in the lake are floating masses of the introduced aquatic weed water hyacinth.

Despite being written by a Mexican historian, there are numerous minor historical inaccuracies in the text, though these should not detract from the enjoyment of the average reader.

For instance, in the Chapala entry, illustrated by the same photo used on the cover, it should be Septimus Crowe (not Crow), and the “navigation company with two small steam ships” had nothing to do with Christian Schjetnam. The steamships predated his arrival in Chapala by many years. Schjetnam did however, introduce two small sail yachts to the area, perhaps explaining the confusion. The description of President Díaz’s interest in Chapala appears to imply that he was first acquainted with the lake when he visited “a political crony” in 1904. Actually, Díaz was certainly personally familiar with Lake Chapala from long before this.

The entry for Santa Rosalia repeats the long-held but unproven idea that the main church was designed by Frenchman Gustave Eiffel (of Eiffel Tower fame). The town does have other Eiffel connections, and the church may indeed have been brought lock, stock and barrel from the 1889 Paris World Exhibition. However, research by Angela Gardner strongly suggests that the original designer was probably not Eiffel but was far more likely to have been Brazilian Bibiano Duclos, who graduated from the same Parisian academy as Eiffel. Gardner proved that Duclos took out a patent on prefabricated buildings, whereas she could find no evidence that Eiffel had ever designed a prefabricated building of any kind. Regardless of who designed it, it is certainly a unique design in the context of Mexico, and well worth seeing.

And really, surely this is the main point of this book. It was presumably never intended to be a reliable geographical (or historical) primer, but rather an enticing selection of seductive places, many of which will be unfamiliar to any but the most traveled reader. The variety of places included is breathtaking; few countries on earth can possibly match it. As such, One Hundred and One Beautiful Small Towns in Mexico is a resounding success.

This beautifully illustrated book should certainly tempt readers to venture into new parts of Mexico in search of these and other memorable places. Enjoy your travels!

– – – –

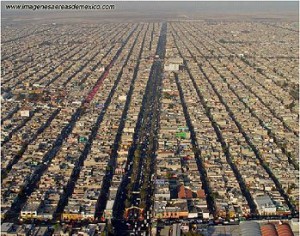

Mexico’s cities and towns are analyzed in chapters 21, 22 and 23 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico. Buy your copy today!!