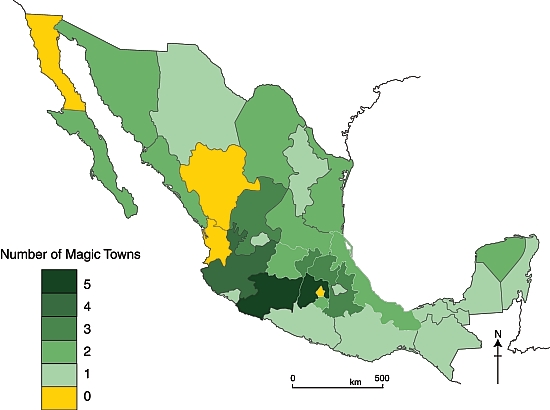

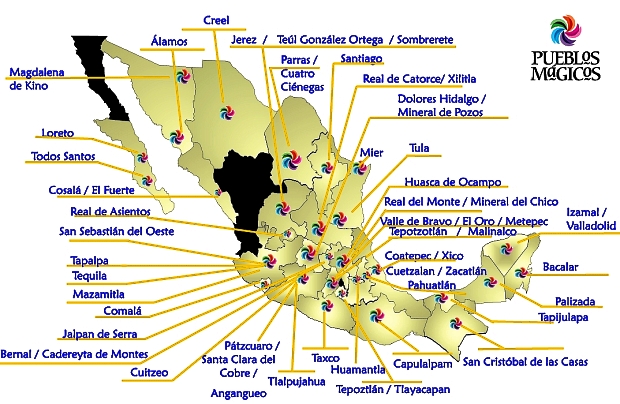

Well… the spate of Magic Town nominations shows no sign of slowing down. The federal Tourism Secretariat has announced that it hopes to have 70 towns in the program before the new administration takes office in December. The latest five additions to the list of Magic Towns are:

#58 Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas

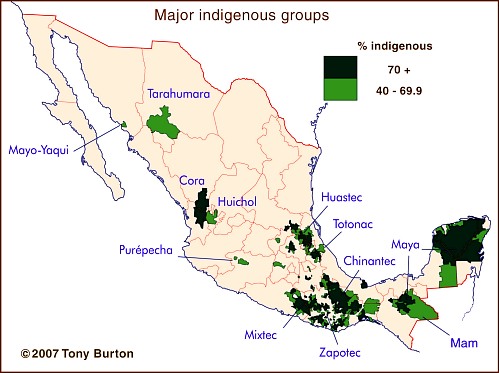

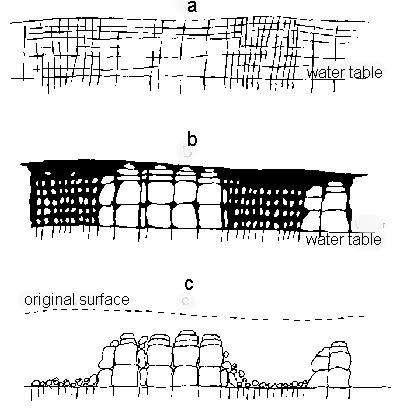

Chiapa de Corzo is a small city (2010 population: 45,000), founded in 1528, located where the PanAmerican Highway (Highway 190) from Oaxaca to San Cristobál de las Casas crosses the River Grijalva, 15 km east of Tuxtla Gutiérrez, in the state of Chiapas. It is the site of the earliest known Mesoamerican tomb burial and has considerable archaeological significance. The massive La Pila fountain, dating from 1562, is one of the most distinctive structures anywhere in Mexico. The town has more than its share of historical interest, including the well-preserved 16th century Santo Domingo church/monastery and a museum dedicated to traditional lacquer work (a local craft). It is best known to tourists as the main starting point for boat trips along the Grijalva River into the Sumidero Canyon National Park.

#59 Comitán de Domínguez, Chiapas

Comitán is a town of about 85,000 people, south-east of San Cristobál de las Casas, and close to the border with Guatemala. The town attracts mainly Mexican tourists on their way to the Lagunas de Montebello National Park and several remote Mayan archaeological sites in the border zone.

#60 Huichapan, Hidalgo

Huichapan has some interesting history and architecture, but relatively little to interest the general tourist. (Even Wikipedia has little to say about this town!)

#61 Tequisquiapan, Querétaro

This very pretty town has already been described in several previous posts on geo-mexico.com, including:

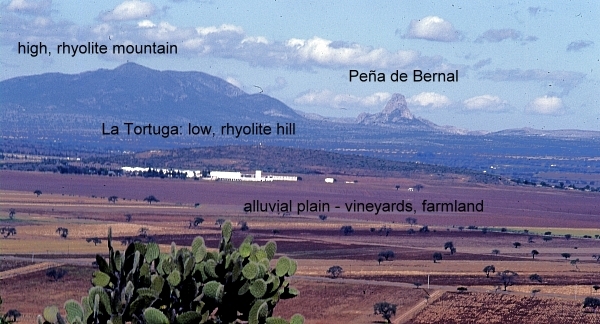

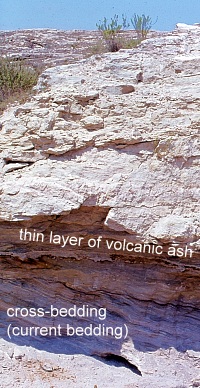

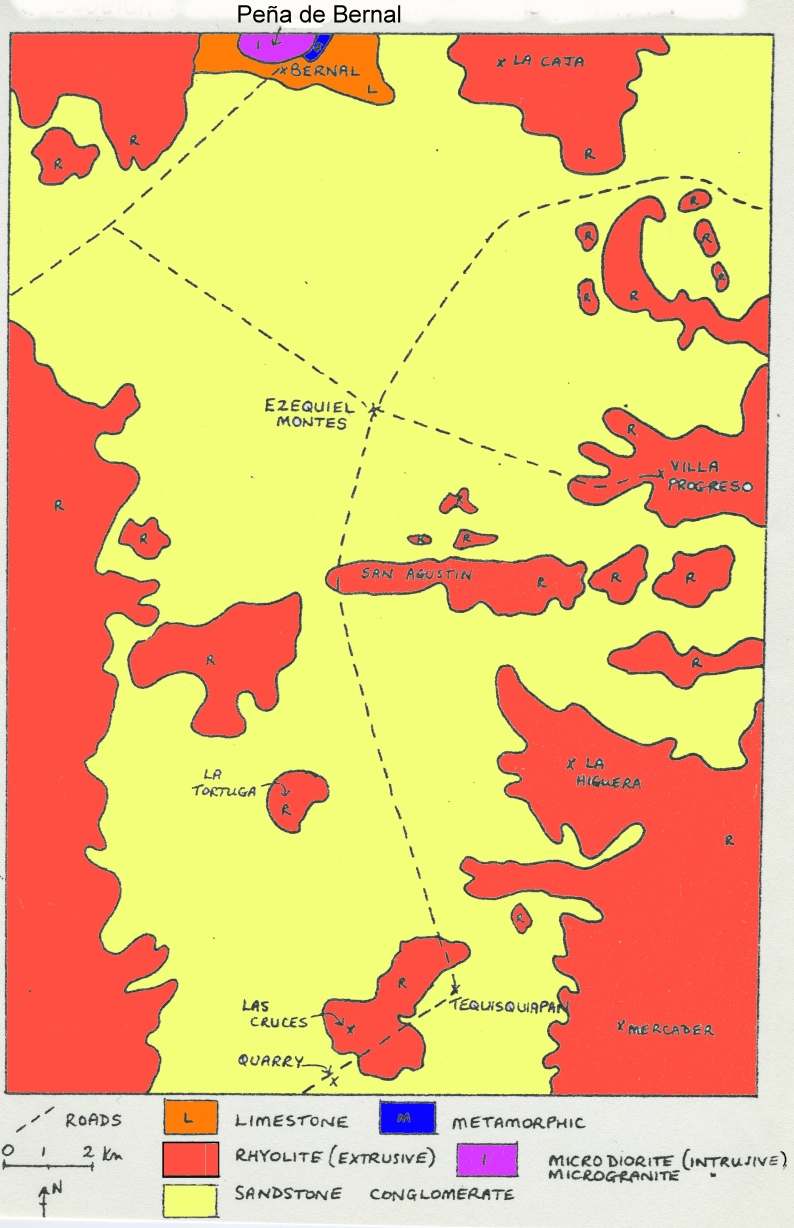

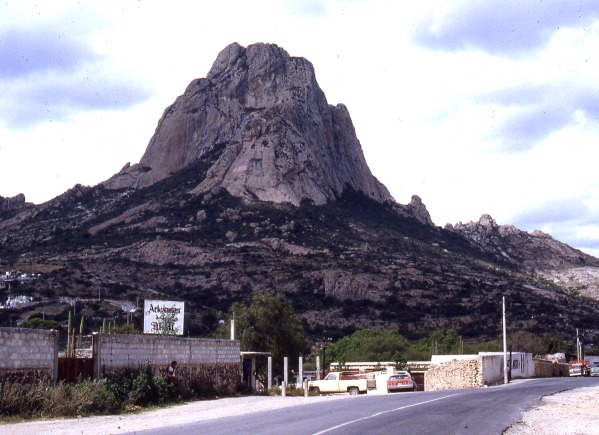

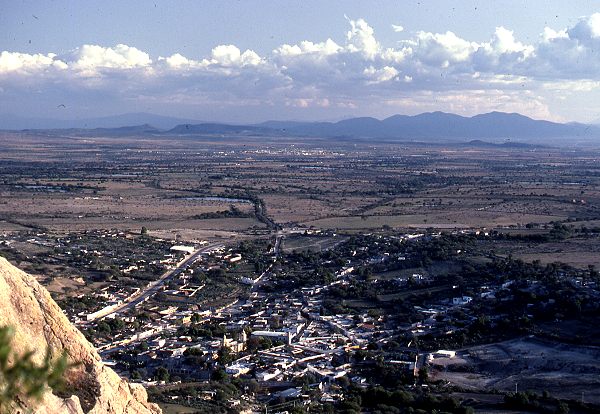

- The geography of Tequisquiapan, a spa town in the state of Querétaro

- Rocks and relief fieldtrip: Tequisquiapan and the Peña de Bernal

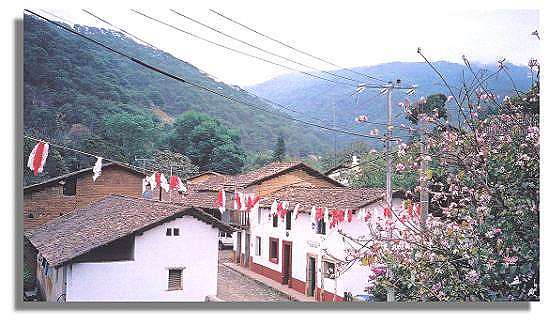

#62 Batopilas, Chihuahua

Designated in mid-October 2012. This small town, situated at an elevation of 501 meters above sea level, on the floor of the picturesque Batopilas Canyon, in Mexico’s Copper Canyon region, was once an important silver-mining center. The great German explorer, Alexander von Humboldt called Batopilas the “metallic marvel of the world”. Some of the old buildings in Batopilas have been restored in recent years. Still in ruins is the former dwelling of Alexander Robert Shepherd, one-time Governor of the District of Colombia, USA.

In 1880, Shepherd moved here, complete with family, friends, workers, dogs and grand-piano. His son, Grant Shepherd, describes in his book, The Silver Magnet, how this piano, the first ever seen in this part of Mexico, was carried overland more than 300 km in three weeks by teams of men, each paid the princely sum of US$1.00 a day for his efforts! Shepherd lived here for thirty years, running a silver mine and entertaining stray foreigners who passed through. He employed English servants. When the Mexican Revolution began, he abandoned Batopilas and the mansion fell into ruins. Shepherd is said to have mined more than US$22 million worth of silver here; he was behind the amalgamation of all the mines into a single company, the Consolidated Batopilas Mining Co. in 1887.

Related posts:

- The distribution of Mexico’s Magic Towns (with links to many earlier posts)

- Mexico’s Magic Towns program going international