How many indigenous people are there?

According to INEGI figures, about six million Mexicans over the age of five speak at least one indigenous language. Another three million Mexicans consider themselves indigenous but no longer speak any indigenous language.

How many indigenous towns or villages exist?

INEGI figures show that, in over 13,000 localities, more than 70% of the population speaks an indigenous language. Most of these localities are small rural settlements with fewer than 500 inhabitants. These settlements are often highly marginalized, with high levels of poverty.

Speaking an Indian language is associated with disadvantage

Speakers of indigenous languages fall way below the Mexican average on almost any socio-economic indicator. For instance, almost 33% of indigenous-speakers are illiterate, compared to a national rate of 9.5%. Females are particularly disadvantaged – indigenous females stay in school a full year less than their male counterparts, and for only half the time that the average non-indigenous female does. Even today, almost 5% of indigenous infants die before reaching their first birthday. A third of indigenous houses lack electricity; more than half do not have piped water.

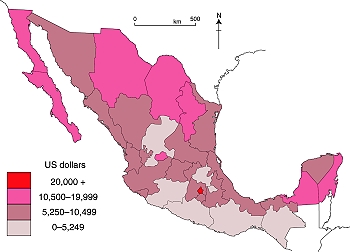

Where do the indigenous people live?

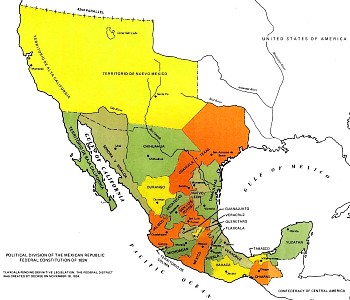

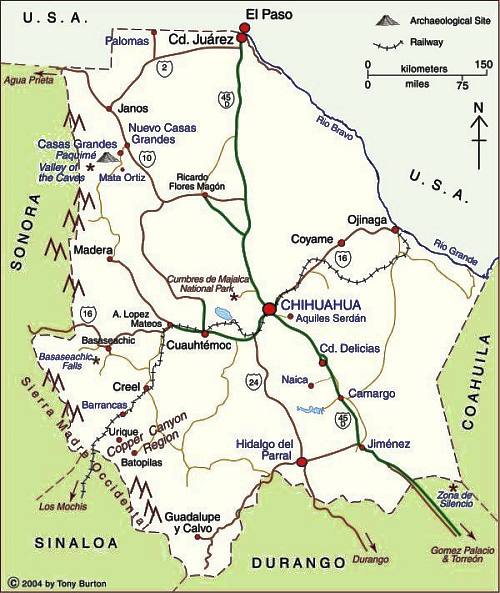

More than 92% of the indigenous population lives in central and southern Mexico. With the notable exception of the 50,000+ Tarahumara Indians who live in the remote Copper Canyon region of Chihuahua, other indigenous groups in northern Mexico have relatively small populations.

The reason is largely historical. The major pre-Columbian civilizations in Mexico—Maya, Aztec, Zapotec, etc—developed in central or southern Mexico. The north always had fewer indigenous people. The disparity in numbers between north and south was heightened in early colonial times, as Spain expanded its territorial interests in New Spain along two major axes of economic development: the Mexico City-Veracruz corridor (the major trade route linking the capital to the port and Europe) and the Mexico City-Zacatecas corridor (the major route linking the capital to valuable agricultural and mining areas). It is no coincidence that indigenous languages and customs first died out along these corridors, as the indigenous people were forced to become assimilated into the developing dominant culture.

Indigenous peoples and languages did much better in the south. At last count, Oaxaca has over one million indigenous speakers representing more than a third of the state’s population. The state’s largest indigenous linguistic groups are the Zapotec, Mixtec, Mazatec, Chinantec, and Mixe. Oaxaca’s ethnic diversity is celebrated in the annual Guelaguetza festival, normally held in July.

Chiapas has almost as many indigenous speakers as Oaxaca. The largest indigenous groups in Chiapas are the Tzotzil, Tzeltal and Chol. One numerically-small Chiapas group is the Mam. Its recent history is an interesting study in how an indigenous group can re-invent itself in order to survive in the modern world.

The population figures quoted in this post are from INEGI’s Census and II Conteo de Población y Vivienda 2005 (INEGI, Aguascalientes).

Click here for original article on MexConnect

Chapter 10 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico is devoted to Mexico’s indigenous peoples. Many other chapters of Geo-Mexico include significant discussion of the characteristics of, and development issues facing, Mexico’s many indigenous peoples.