Every two years, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) awards the Equator prize (worth 30,000 dollars) to communities that have shown “outstanding achievement in the reduction of poverty through the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity.”

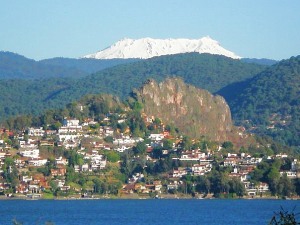

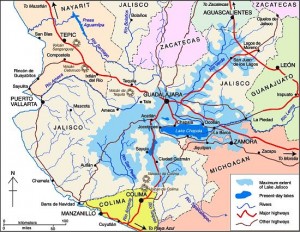

One of the winners of the 2004 Equator prize was the indigenous community of Nuevo San Juan Parangaricutiro, in the state of Michoacán. More than 340 communities, from 65 countries, were nominated for consideration by the Equator Prize jury. The seven winning communities were honored at a prize-giving ceremony held in conjunction with an international Biological Diversity Conference in Kuala Lumpur, in Malaysia.

The success of Nuevo San Juan Parangaricutiro (hereafter referred to simply as Nuevo SJP) is all the more remarkable since their community did not even exist prior to 1944.

That is the year when all the founding residents of Nuevo (New) SJP fled their homes in “viejo” (Old) SJP as the sizeable town was overwhelmed by the lava erupting from Paricutín volcano. Paricutín first erupted, completely unexpectedly, in the middle of a farmer’s field, on February 20, 1943. It is a sobering thought that only 61 years to the day before the prize-giving, the volcano literally did not exist.

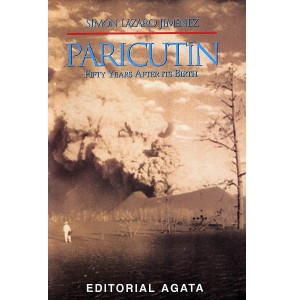

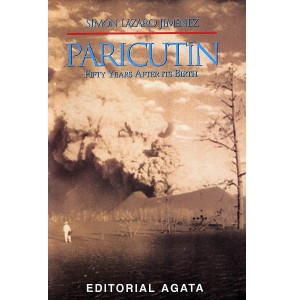

A remarkable account of those early days is given by Simón Lázaro Jiménez, who recounts in his book, Paricutín: 50 Years After Its Birth, his adventures as a young boy as he fled with his parents for safety as their small village of Angahuan was bombarded with red-hot rocks and ash. Don Simón’s is the only first-hand account of any substance written by a native P’urépecha speaker.

A remarkable account of those early days is given by Simón Lázaro Jiménez, who recounts in his book, Paricutín: 50 Years After Its Birth, his adventures as a young boy as he fled with his parents for safety as their small village of Angahuan was bombarded with red-hot rocks and ash. Don Simón’s is the only first-hand account of any substance written by a native P’urépecha speaker.

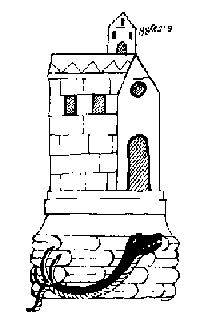

The volcano finally stopped erupting in 1952, but only after completely destroying the village of Parícutin (note that the position of the accent has changed over the years) and the town of viejo SJP. All that is left of the latter today are a few broken-down walls and parts of the huge, old church that did a brave job of withstanding the compelling force of the lava as it overran the rest of the town.

The people who fled the volcano (many initially refused to leave, but were escorted to safety by armed soldiers) stayed with friends and relatives and in makeshift camps before finding permanent accommodation, but later in 1944, founded Nuevo SJP after a presidential decree gave them land formerly belonging to the hacienda of Los Conejos.

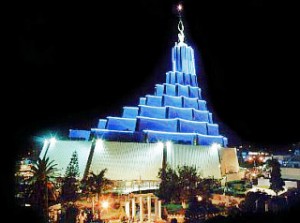

The new town had to be completely planned from scratch. A gigantic church was built to commemorate the miraculous survival of part of the Old San Juan church which formed a partial barrier to the lava flow. Little by little a new community evolved, fostered in part by the high degree of cooperation required for building a new town and working virgin land.

In 1977, motivated by the abuse of local forest lands by private concession holders, the campesinos of Nuevo SJP organized their own union for farming and forestry workers. In 1981, they began their own forestry industry, and now collectively own and manage more than 11,000 hectares of pine, oak and fir forest. Over the years, their business activities have diversified to include a saw mill, a furniture factory (which has won export orders from Belgium and Ireland), a plant making wooden moldings for export to the USA, avocado and peach orchards, a packing plant which makes its own cases, a Christmas tree plantation, eco-tourism cabins and a resin distillation plant, as well as a store for the bulk purchase and resale of fertilizers. A water bottling plant, to bottle spring water, is one of the community’s latest proposals.

The community’s website gives details of all these activities and includes a link to a furniture catalog for those interested in buying direct. All the wood used is certified as “Smart Wood” (coming from well-managed forests) by the Forest Stewardship Council.

Community decisions in Nuevo SJP are made on behalf of the 8,000 or so residents by a General Assembly of the 1,300 Comuneros (community representatives), which has met at least once a month since 1983.

The Equator Prize was awarded because the forest policies adopted by the community “have provided a boost to local incomes while ensuring that the resource base upon which the community depends is sustained for future generations.” In addition, “the community’s successes have spread well beyond their origins as these novel conservation and business practices have been widely adopted by other indigenous communities in Mexico.”

Nuevo SJP may not be very old, or very large, but it certainly has a really big heart!

For a more detailed account of the history of the volcano, and of the considerable architectural attractions of the village of Angahuan, including its superb church, read chapter 35 of Western Mexico: A Traveler’s Treasury (Sombrero Books 2013).

Original article, as published on MexConnect

Mexico’s Volcanic Axis is discussed in chapter 2 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico. The sustainable forestry project of San Juan Parangaricutiro is examined in chapter 15.