A short piece in The Economist entitled “Maternal Health in Mexico: A perilous journey” (26 June 2010) highlights some of the reasons why maternal mortality has remained stubbornly high in southern Mexico, despite a marked improvement in recent years. Since 1990, maternal mortality (death related to childbearing) has fallen by 36% in Mexico as a whole.

Carrying the future; maternal mortality remains alarmingly high. Photo: Tony Burton. All rights reserved. Click to enlarge.

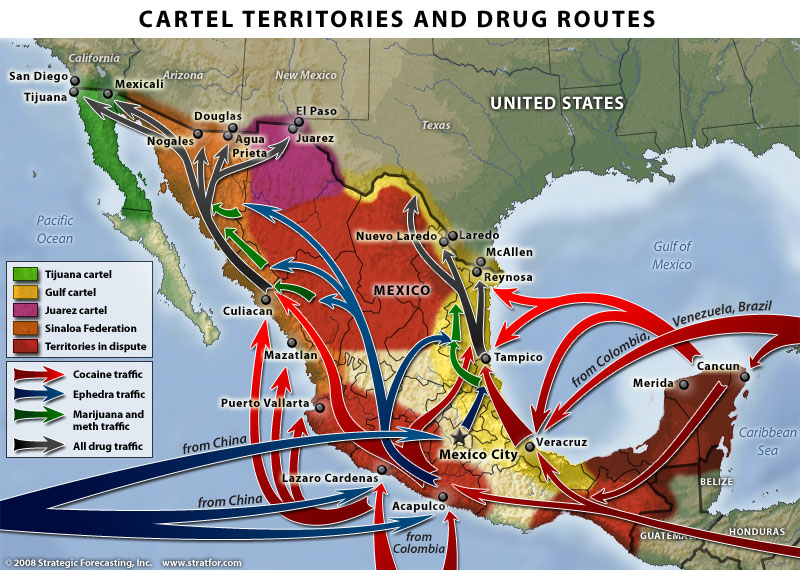

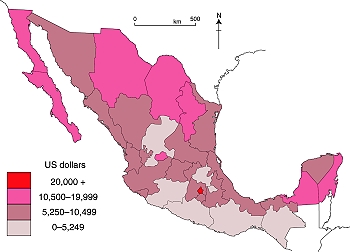

Any average figure for the whole country disguises enormous regional differences. Rates for the richer inhabitants in the more developed regions in Mexico are comparable to rate in the USA or Canada. However, rates in the impoverished southern states such as Chiapas, Oaxaca and Guerrero are up to 70% higher than the national average.

In the words of the Research for Development blog “In 2005 the maternal mortality rate was 63.4 deaths per 100,000 live births. In the state of Guerrero the rate rose to 128 deaths per 100, 000 live births. Both figures are a long way from Mexico’s commitment under the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) of 22.3.” Click here to see how well Mexico is doing in meeting other MDGs.

One study found that in the year 2000, only 44.8% of women in Chiapas gave birth with a doctor present; 49.4% did so with midwives, and the remaining 5.8% were attended by family members or give birth alone.

As The Economist article emphasizes, indigenous women are only one-third as likely to survive giving birth as non-indigenous women.

Why is this? What are the key factors preventing lower maternal mortality rates?

The Economist singles out:

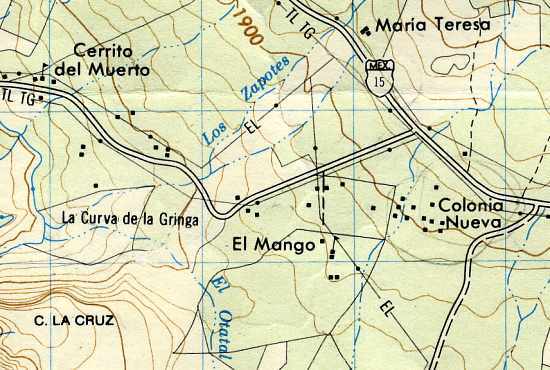

- means of transport – lack of a car means a total reliance on public transport. Public transport is poor in many remote areas

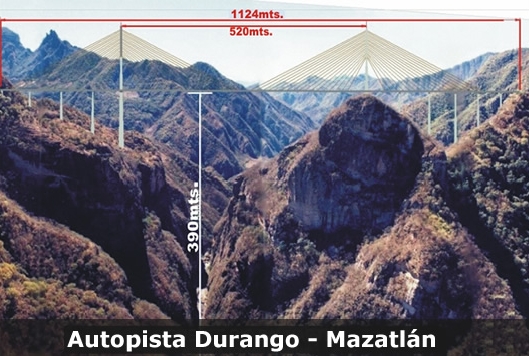

- poor roads – many rural roads are unpaved, and the terrain in much of Mexico means than travel times are often much longer than might be expected

- the expense of the hospital tests and medical supplies which can save a mother’s life

- errors in delivery care or hospital procedures – according to The Economist, “40% of urban maternal deaths are caused by using the wrong medicine, by botched surgery or by other forms of malpractice.”

- reluctance to see a male doctor (for social or cultural reasons)

- language issues – many indigenous women do not speak Spanish at all well, if at all, and very few doctors have any knowledge of indigenous languages, so communication is often poor

What is needed to reduce maternal mortality rates? Understandably, The Economist focuses its attention on financial or economic solutions. More money is needed, it argues, for “midwifes and contraceptives.” It reports that increased funds are coming from a variety of sources, including the Spanish government, Carlos Slim (the Mexican entrepreneur who is the world’s richest man) and from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Between them, they have announced plans to spend 150 million dollars “on health care for the poor in Central America and southern Mexico”.

In addition, the article calls for investment in “infrastructure, health and education”, making the claim that investment in these areas would help the south catch up with the rest of the country.

We consider this analysis of possible remedies for the problem to be incomplete. The political will to continue making investments in health care installations and personnel over the long-term requires, in our opinion, a significant shift in attitudes among the wealthier and more influential sectors of Mexican society.

At present most members of the wealthy elite regard indigenous Mexicans as second class citizens.

At the time of the Chiapas uprising in 1994, for example, a subset of well-educated Mexicans called on the government to resolve the problems the nation faced in southern Mexico once and for all by using maximum force to re-establish complete military control over the area. Fortunately, the government of the day did not follow their advice but opted for alternative approaches such as dialogue.

Mexico’s indigenous peoples are rarely shown on TV or in advertisements. Instead, most firms prefer to picture blond, blue-eyed mestizos. Alongside increased financial investment in the south, a massive shift in public perception is required. For everyone’s sake, let us hope that this can be achieved with a minimum of turmoil.

Mexico’s government has to make tough choices about how far the national budget can stretch, and which things should be prioritized. Decisions are often based on political expediency as much as on the nation’s pressing development needs. Indigenous peoples are not well represented in federal government.

At present, the best-trained physicians and nurses aspire to work in the world class medical facilities in Mexico’s major cities. Health care workers in Mexico’s remote areas are often there only to fulfill the social service requirements for their professional qualification; they perform valuable work, but certainly have no long-term commitment to these regions. In the words of a MacArthur Foundation researcher (quoted in “Evaluation of The MacArthur Foundation’s Work in Mexico to Reduce Maternal Mortality, 2002-2008”) , qualified doctors (residents) “see their work as a big favor they do for the community, rather than understanding that indigenous populations in our country also have a right to health.”

We believe that a change in how society perceives indigenous peoples is a fundamental prerequisite for genuine long-term change, particularly in states such as Chiapas and Oaxaca.

Mexico’s indigenous populations, and the disparities in wealth and opportunity they face, are analyzed in chapters 10 and 29 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico. Ask your local or university library to buy a copy today!!