Dr Carl Wilhelm Schiess (1869-1929) is the unexpected link between Mexico and a Swiss castle. Schiess wrote a travel account, first published in 1902, of a two-month trip in Mexico in the winter of 1899-1900. The account, only ever published in German, is Quer durch Mexiko vom Atlantischen zum Stillen Ocean (“Across Mexico from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean”), published in Berlin by Dietrich Reimer.

Early travel accounts of Mexico are a valuable source of information for historical geographers, as well as for armchair travelers. Schiess’s account is no exception.

Who was Carl Wilhelm Schiess?

Carl Wilhelm Schiess of Basel and Herisau was born on 12 July 1869. His father was Prof. Dr. Heinrich Schiess, a well-known ophthalmologist in Basel, and his mother Rosalie Gemuseus. After completing his medical studies, the young doctor traveled abroad. These travels included a trip with his brother to Mexico over the winter of 1899-1900.

Where did they travel in Mexico?

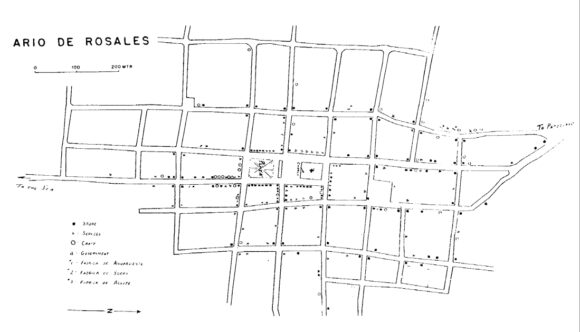

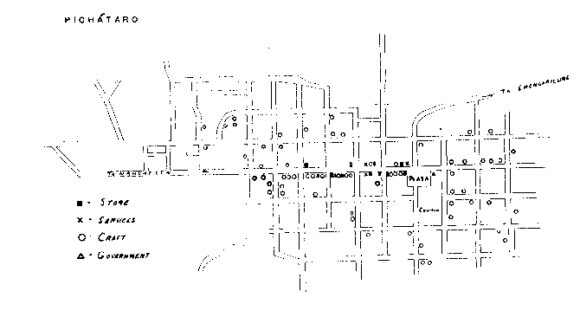

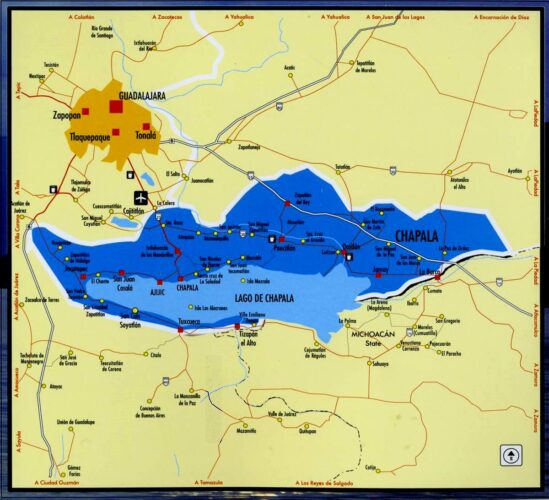

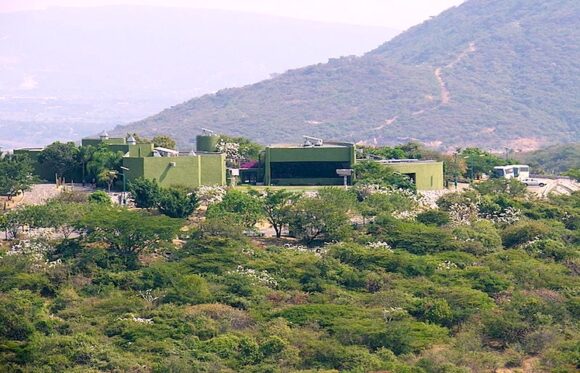

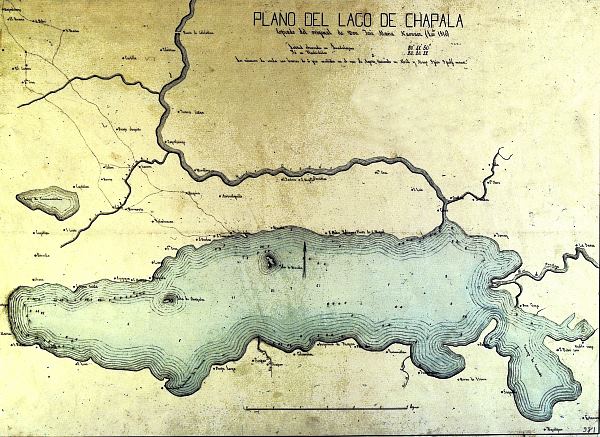

They entered Mexico (and returned) via New Orleans. The brothers traveled by rail to Torreón, and then to Durango, before crossing the Western Sierra Madre to Mazatlán. From Mazatlán, they took a steamer to San Blas, and then proceeded to cross the country from west to east, via Tepic, Tequila, Guadalajara, Chapala, Zamora, Uruapan, Pátzcuaro, Morelia, Mexico City, Amecameca, to Veracruz, before returning north via Orizaba, Cordoba, Guanajuato, Aguascalientes and Zacatecas. Quite the itinerary to complete in just two months!

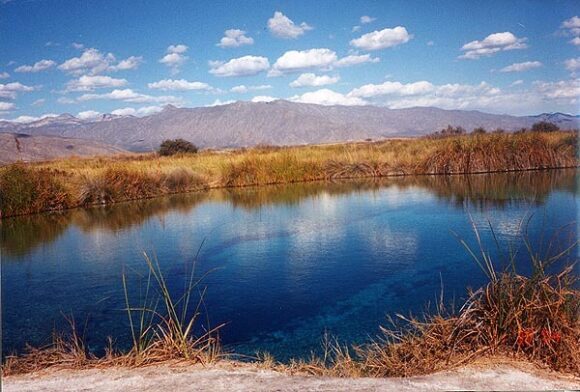

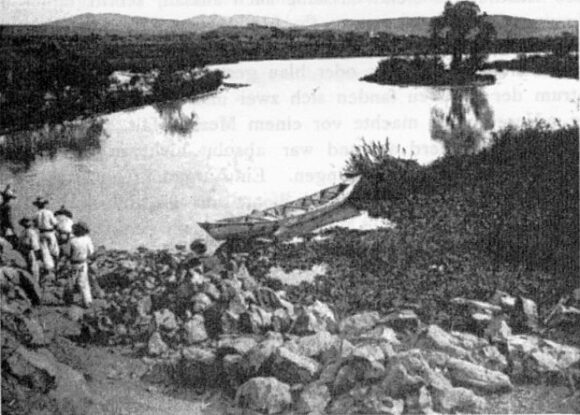

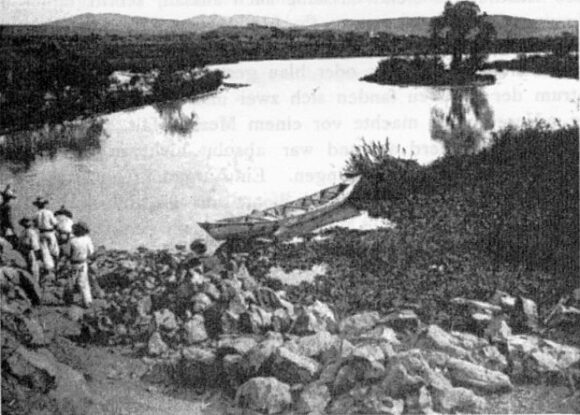

They were very impressed by the grandeur of the Juanacatlan Falls and the book includes several photographs of that area, including the falls themselves, women washing clothes below the falls, and this photo of an unpolluted River Santiago (aka Rio Grande) immediately before the falls.

Wilhelm Schiess: Rio Grande, Juanacatlan (December 1899)

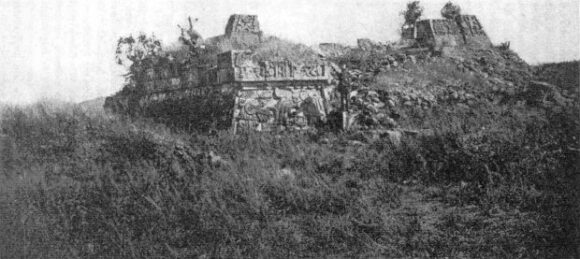

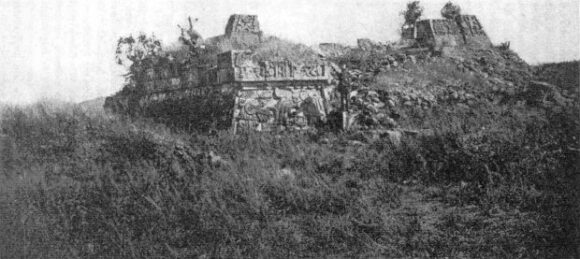

Schiess and his brother had plenty of adventures along the way. Like most other early travelers in Mexico, they made a point of climbing Popocatepetl Volcano, but the brothers went one better than most and photographed the interior of its crater. The two men made several trips to places, such as mines, that were well off the beaten track. In central Mexico, they took the time to explore the ruins of Xochicalco, an archaeological site that even today is often ignored by passing tourists. The main pyramid at that time (photo) had not been restored.

Wilhelm Schiess: Xochicalco (December 1899)

Schiess’ account of their travels in Mexico is essentially a factual, straightforward account of their impressions and what they did, with few digressions, more of a journal than a modern-day travel book. It was well received at the time as an accurate, first-hand account of several little-known parts of Mexico.

A review in the Bulletin of the American Geographical Society claimed that, “His route from Durango across the Sierra Madre to Mazatlan has perhaps never been described before, and the interesting regions he crossed between San Blas and Lake Chapala are not well-known.” It probably is unlikely that the Durango-Mazatlan route had been described in detail prior to Schiess, though (by coincidence) Carl Lumholtz’s Unknown Mexico, which covers some of the same ground, and was based on travels between 1890 and 1900, was also first published, like Schiess’s book, in 1902.

However, the reviewer’s claim that the “regions” between San Blas and Lake Chapala were not well known is a clear exaggeration, since there had been several earlier, detailed, first-hand descriptions of the route from San Blas via Tepic to Guadalajara (and Lake Chapala) on account of this being a major trading and smuggling route during the nineteenth century.

Wilhelm Schiess: Street in Pátzcuaro (December 1899)

While one reviewer of Schiess’ book lamented the lack of reference to any earlier writers, all agreed that the inclusion of 71 photographs, many of high quality, made the book a valuable addition to the existing literature about Mexico.

Sadly, and presumably because the book was never translated into any other language, Schiess’s work has never received very wide attention.

Schiess’s account of Mexico is interesting in its own right, but his personal story after the trip to Mexico is just as interesting.

Scheiss’s connection to a Swiss castle

In 1900, shortly after his return to Switzerland, Schiess’s aunt, Mrs. Rosina Magdalena Gemuseus, bought Spiez Castle, on Lake Thun in the Swiss canton of Bern. Parts of the castle date back to the tenth century.

On 28 July 1900, Schiess opened his medical practice – in the castle. Announcing in a local newspaper that his practice was now open at Spiez Castle, with office hours daily in the morning to 11 clock, and with a clinic for eye diseases on Tuesday and Friday mornings, Schiess practiced and lived in the castle for many years, though it is not known which living spaces were used by either his aunt, or the doctor and his wife.

The village of Spiez grew rapidly after 1900. Roads were improved and villagers added a new stone church and many new homes. In about 1906, Dr. Schiess commissioned a firm of Basel architects to build him a large home in the village, to house both his family and his medical office. In other respects, Schiess lived quite modestly, continuing to make his rounds to visit patients by bicycle. Contemporaries described Schiess as a friendly, helpful and keen doctor, who, during the terrible 1918 flu epidemic, worked tirelessly, with no breaks, for several months.

In 1907, Schiess’s aunt sold him some of the outlying castle properties, including the old church, rectory, manager’s house, cherry orchard, vineyards and an area of forest. After his aunt’s death on 3 February 1919, the castle itself passed to Schiess. However, the upkeep was costly, and Schiess soon found himself having to sell valuable objects from the castle to pay for its ongoing maintenance.

By 1922, Schiess was actively looking for potential purchasers. A group of villagers established a foundation with the idea of preserving the castle for future generations. On 1 August 1929, the Spiez Castle Foundation and Schiess agreed terms for the sale of the castle. Barely two weeks later, on 14 August 1929, Schiess died unexpectedly of heart failure.

The castle and gardens first opened to the public in June 1930. The castle rooms are now used for conferences, concerts, exhibitions and other events.

Sources

- Wilhelm Schiess. 1902. Quer durch Mexiko vom Atlantischen zum Stillen Ocean. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer.

- Alfred Stettler. 2004. “75 Jahre Stiftung Schloss Spiez: Die Anfänge” (“75 years of the Spiez Castle Foundation: The beginnings”) in Jahrbuch: vom Thuner und Brienzersee, 2004 (“Yearbook of the lakes Thun and Brienz, 2004). Uferschutzverband Thuner- und Brienzersee.