Tomatoes are one of the many native Mexican plants that have become essential ingredients in the cuisine of many countries. Mexico is the 10th largest tomato producer in the world, after China, USA, India, Turkey, Egypt, Italy, Iran, Brazil and Spain (FAO 2008).

Mexico produces both red tomatoes (tomate or jitomate, depending on the region) which have high yields and account for about 75% of total tomato production, and green tomatoes (tomate verde) which have a lower yield and account for the remaining 25% of production.

The statistics in this post apply to the production and export of red tomatoes only.

The main varieties of red tomatoes in Mexico are:

- vine-ripe large rounds

- cherry tomatoes

- Roma tomatoes, which now account for 54% of all tomato plantings in Mexico, as demand for them has increased at the expense of other kinds

- greenhouse tomatoes (the collective name for several other varieties)

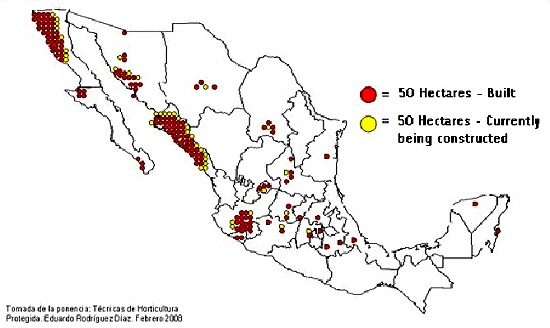

Greenhouses

The single most significant trend in tomato growing in Mexico is the increasing volume of production coming from greenhouse (including shade house) cultivation. Greenhouse cultivation still represents only a small portion of total tomato production in Mexico, but results in greatly improved yields.

Mexico has around 3,200 hectares of horticultural greenhouses in total. An earlier post analyzed the essential characteristics and advantages of the production of horticultural products in greenhouses.

The major advantages for tomato production are:

- helps to raise yields

- enables producers to move away from seasonal production and grow tomatoes virtually the entire year

- ensures a higher quality and consistency of product

- facilitates better food safety

- helps to ensure that production and packing plants meet or exceed international standards

Rising yields

Yields are rising. Open field yields have risen from 23 metric tons/ha in 1990 to 28 mt/ha in 2000 and to 39 mt/ha in 2010. The highest open field yields are about 45 mt/h in Baja California and Sinaloa, due in part to their efficient pest and disease control protocols.

Greenhouse cultivation of tomatoes gets much higher yields, but also requires more capital investment and more expensive inputs of labor, fertilizers and pesticides. Open field cultivation of tomatoes in Sinaloa and Baja California costs between $3,800 and $6,000/ha. Greenhouse and shade house production of tomatoes can cost up to $22,000/ha. (All figures in US dollars.) The costs associated with many imported inputs (agrochemicals, seeds and fertilizers) are high; they are also dependent on the peso/dollar exchange rate.

Greenhouse yields in Mexico are generally about 150-200 mt/ha. Tomato growers in the USA and Canada using greenhouses achieve yields of up to 450mt/ha, so Mexican producers still have plenty of room for continued improvement.

The largest area of greenhouse tomato cultivation is in Spain (20,000 hectares). By comparison, the USA has only around 350 ha of greenhouse tomatoes, Canada has 650 ha and Mexico 730 ha.

Area cultivated and volume of production

The total area (greenhouse and open field) devoted to tomato cultivation in Mexico has decreased in recent years, from 85,000 ha in 1990 to about 60,000 in 2010.

Tomato production in Mexico for the 2010/11 season is forecast to reach 2.2 million metric tons.

Seasonality

There are two major seasons:

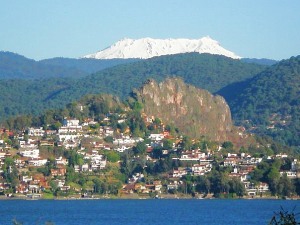

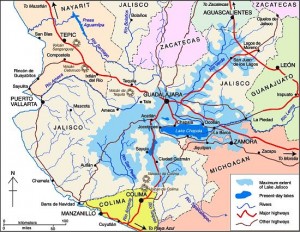

1. In the winter season (October-May), growers in Sinaloa are the main producers and exporters of fresh tomatoes. Michoacán, Jalisco, and Baja California Sur also produce significant amounts in the winter season. Sinaloa growers have adopted very modern cultivation methods, selecting varieties with an improved and extended shelf life, employing highly efficient drip irrigation, and using plastic mulch to maintain their high yields. Sinaloa has 15,000 hectares devoted to tomatoes, of which 1,340 hectares are using greenhouses or shade houses.

2. During the summer season (May-October), growers in Baja California are the main producers and exporters of fresh tomatoes, along with growers in Michoacán, Jalisco, and Morelos.

Mexico Exports: Tomatoes

Domestic consumption and the export market

The final consumption figure for the domestic market depends largely on the volume of tomato exports (primarily to the USA), since domestic consumption is essentially restricted to those tomatoes that do not enter the export flow. Volumes of exports, and price/ton depend on numerous factors beyond the control of farmers in Mexico, including, for example, the seasonal weather in Florida which will help determine the volume of tomatoes produced in the USA.

The USA imports tomatoes from both Canada and Mexico. Mexico’s share of USA tomato imports has risen rapidly since 2000 on account of their lower costs. Mexican tomatoes are less expensive for USA buyers than their Dutch or Canadian counterparts, due to Mexico’s cheaper labor rates, lower transport costs, and their modern cultivation and packing systems.

Mexico’s 1.1 million tons a year of tomato exports are worth 1.1 billion dollars. Mexico does import some tomatoes, but the annual value of imports rarely exceeds 65 million dollars.

Potential risks faced by Mexico’s tomato growers

- extreme heat may make tomatoes ripen earlier than usual, as happened in Sinaloa in December 2009

- the switch from open field tomato production to protected production (in greenhouses or shade houses) requires an expensive investment in infrastructure and technology.

- international prices each year are a major determinant of how many hectares of tomatoes are planted the following year

Note on the first GM tomato

The first GM tomato to be commercially cultivated was the Flavor Saver from the Calgene company, planted in 1995 in Mexico, California and Florida. It was marketed as the MacGregor tomato. It was primarily developed because it did not spoil as quickly as previous varieties of tomato. MacGregor tomatoes last at least 18 days without spoiling, from the time they are picked. Conveniently, consumers also preferred their taste to then-existing varieties. Developing the first GM tomato cost Calgene 25 million dollars and took 5 years.

Main source:

Flores, D and Ford, M. Tomato Annual: area planted down but production up. USDA Foreign Agricultural Service GAIN (Global Agricultural Information Network) Report, January 2010