A short distance north of San Blas, in Nayarit, is a small island called Mexcaltitán. With barely four thousand inhabitants, it would scarcely be expected to have any real link to Mexico City, the world’s greatest metropolis of some twenty million people. But it does, and the link is to be found in the amazing story of the founding in 1325 of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan, the city which was later conquered and sacked by the Spanish and rebuilt as Mexico City.

The island and village of Mexcaltián, Nayarit

Historians have long wondered about the origins of the Mexica people, or Aztecs as they later became known. There is virtually no evidence of them before they founded the highly organized city of Tenochtitlan in 1325. Clearly such a civilization cannot just have sprung up overnight. So, where did they come from? Mexica (Aztec) legend tells of a long pilgrimage, lasting hundreds of years, from Aztlán, the cradle of their civilization, a pilgrimage during which they looked for a sign to tell them where to found their new capital and ceremonial center. The sign they were looking for was an eagle, perched on a cactus. Today, this unlikely combination, with the eagle now devouring a serpent, is a national symbol and appears on the national flag.

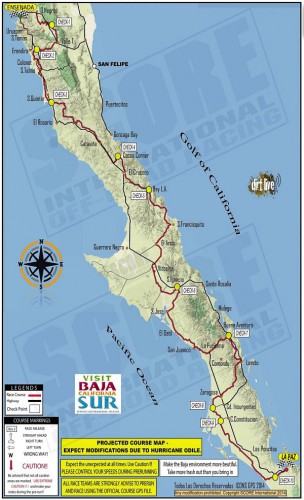

Map showing location of Marismas Nacionales

In recent years more and more evidence suggests that Aztlán may be far from mythical and that Mexcaltitán, the island in Nayarit, could be its original site. Ancient codices (pre-Columbian hand-painted manuscripts) prove that the Aztecs’ search for a new place to live was ordained by Huitzilopochtli, their chief god. It began in about AD1111 when they departed from an island in the middle of a lake. Their two hundred year journey took them through present-day Nayarit, Durango, Zacatecas, Jalisco, Michoacán, Guanajuato and Querétaro, and they may well have rested awhile on encountering familiar-looking islands in the middle of lakes such as Chapala and Pátzcuaro.

One of Huitzilopochtli’s alternative names was Mexitli and the current spelling of Mexcaltitán could be interpreted as “Home of Mexitli”, or thus, “Home of Huitzilopochtli”. In fairness, it should be pointed out that if the original spelling was Metzcaltitán (and “tz” often became transliterated to “x” down the centuries), then the meaning would become “Place next to the home of the Moon”.

Whatever the etymology of the name, early codices such as the Boturini Codex show the early Aztecs setting out from an Aztlán surrounded by water, in small canoes. The Mendoza Codex, depicting life in Tenochtitlan, has illustrations of similar canoes and, in both codices, the canoes and method of propulsion by punting show remarkable similarity to the present-day canoes of Mexcaltitán. Visitors to the island still have to undertake a canoe or panga ride to reach the village and it is an intriguing thought that the Mexica/Aztecs were doing exactly the same over eight hundred and fifty years ago.

Further evidence comes from an old map of New Spain. Drawn by Ortelius in 1579, it shows Aztlán to be exactly where Mexcaltitán is to be found today, though perhaps at the time this was largely conjecture.

The street plan of Mexcaltitán, best appreciated from the air, is equally fascinating. Two parallel streets cross the oval-shaped island from north to south, and two from east to west, with the modern plaza in the middle, where they intersect. The only other street runs around the island in a circle, parallel to and not far from the water’s edge. This street may have been the coastline of the island years ago and may even have been fortified against the invading waters of the rising lake each rainy season. Today, as then, for several months in summer the streets become canals, bounded by the high sidewalks each side and Mexcaltitán becomes Mexico’s mini-Venice as all travel has to be by canoe.

This street pattern has cosmic significance. It divides the village into four quarters or sectors each representing a cardinal point, reflecting the Mexica conception of the world. The center can be identified with the Sun, the giver of all life. The Spanish, as was their custom, built their church there, and today the central plaza with its bandstand is the obvious focal point of the community. Small shops, a billiards hall, a modern, well-laid out museum, and an administrative office complete the central area of the village.

Mexcaltitán (pen and ink drawing by Michael Eager from chapter 26 of Western Mexico, A Traveler’s Treasury). All rights reserved.

Low houses, of adobe, brick and cement, line the dirt streets and extend right down to the water’s edge, in some cases even over the water’s edge into the surrounding lake, on stilts. Land on the island is at a premium and, with an ever-growing population, saturation point is very near.

A century ago, the locals turned on some foreigners who came to hunt female egrets, valued for their plumes back in the days when feathers adorned fashionable ladies’ hats. Today, provided only photos are taken, all visitors are welcomed! The villagers celebrate one of the most unusual and distinctive fiestas in all of Latin America. On 29 June each year they organize a regatta which consists of a single race between just two canoes, though naturally hundreds of other pangas are filled with spectators. One of the competing canoes carries the statue of Saint Peter from the local church, the other carries Saint Paul.

Elaborate preparations precede the race. The village streets are festooned with paper streamers and the two canoes are lavishly decorated by rival families carrying on an age-old tradition. The Ortíz family is responsible for St. Peter’s canoe, the Galindo family for St. Paul’s. The statues of the two saints are taken from the church and carried in procession to the boats. A pair of punters has previously been chosen from among the young men of the village for each boat. The punters have been suitably fortified for the contest with local delicacies such as steamed fish, shrimp empanadas, and the local specialty, tlaxtihuile, a kind of shrimp broth. Each boat, in addition to the punters and the statue of the saint, carries a priest to ensure fair play. The race starts from the middle of the eight kilometer long lake after a short religious service in which the priests bless the lake and pray for abundant shrimp and fish during the coming year. Then surrounding spectator canoes, some with musical bands, and others shooting off fireworks, move aside and the race begins.

Nowadays, St. Peter and St. Paul take it in turns to win, most considerate in view of the violence which years ago marred the post-race celebrations when the race was fought competitively. The ceremonial regatta safely over, land based festivities continue well into the night.

A canoe ride around the island takes about 30 minutes and provides numerous photo opportunities as well as many surprises including a close-up view of the island’s only soccer pitch—in the middle of the lake, under half a meter of water. The local children are, perhaps not surprisingly, expert “water soccer” players, a fun sport to watch.

Even if you’re not interested in the island’s past and are unable to see it on fiesta day, your trip to Mexcaltitán will be memorable. This extraordinary island and its village have to be seen to be believed.

The island is reached from the Tepic-Mazatlán highway, Highway 15. There are two alternatives. The northern route is signposted 73 kilometers north of Tepic; it starts with 26 kilometers of paved road crossing swampy paddy fields, followed by 16 kilometers of well-graded dirt road to Ticha, the landing-stage for boats to the island. The drive is through a naturalist’s paradise, teeming with wildlife. The equally scenic southern route begins 57 kilometers from Tepic and is via Santiago Ixcuintla (basic hotels only; don’t miss visiting the center for Huichol Indian culture and crafts) and Sentispac. It leads to the La Batanga landing-stage, and is fully paved.

Note:

This post is based on chapter 26 of my “Western Mexico: A Traveler’s Treasury” (link is to Amazon’s “Look Inside” feature), also available as a Kindle edition or Kobo ebook.

Related posts: