The XVI Pan American Games were held from October 14–30, 2011 in Guadalajara (Jalisco) with some events held in outlying locations such as Ciudad Guzmán, Puerto Vallarta, Lagos de Moreno and Tapalpa. They were the largest multi-sport event of 2011. Some 6,000 athletes from 42 nations participated in 36 sports. The largest contingents of athletes (more than 500 in each case) came from host nation Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, the USA, Cuba and Canada.

Guadalajara is Mexico’s second city, a metropolitan area of almost five million people, the industrial and commercial hub of a region that is considered quintessentially Mexican, home to charrería (Mexican horsemanship), jarabe tapatío (Mexican hat dance), mariachi music, and tequila, the national drink.

This post looks at the impacts of the Pan American Games on the local economy.

How much investment was required to host the games?

The original budget for the Games was $250 million (dollars), but this ballooned to about one billion by the time of the Opening Ceremony. The security budget was $10 million, to pay 10,000 municipal, state and federal police, as well as elements from the Mexican army and navy, to patrol the streets surrounding the venues during the games.

How many visitors attended the Games?

The State Tourism Secretariat expected 800,000 visitors and spending of $75 million (dollars). Some government spokespersons claimed that between 1 and 1.5 million attended the games. However, a study released by the Guadalajara Chamber of Commerce found that 454,148 visitors came to Guadalajara during the games (305,177 from the state of Jalisco, and 148,971 from elsewhere). 83% (424,354) of visitors came “specifically for the Games”.

How many jobs were created?

The build-up to the games created some 50,000 new jobs. In addition, more than 6,000 volunteers, mainly students, were employed during the games.

How much were the media and TV rights worth?

1,300 media representatives attended the games. More than 750 television hours of sports were broadcast, with global digital media company Terra broadcasting the games live in 13 simultaneous high-definition online channels. The TV rights were worth $50 million.

How many sports venues were used?

There were 32 different venues used during the games. Billions of pesos were spent building 19 impressive new sports stadiums and complexes. Thirteen existing sports arenas in the Guadalajara metro area were rebuilt or extensively refurbished. The opening and closing ceremonies for the Pan American Games were held in a 48,000-seat local soccer stadium, the Omnilife Stadium (Estadio Omnilife), built in 2010 for the Guadalajara “Chivas” soccer team.

Facilities built specifically for the games included an iconic Aquatics Center (Centro Acuático), sponsored by Scotiabank, with two Olympic-size pools and seating up to 3,500 spectators, and a state-of-the-art gymnastics venue, sponsored by Nissan.

2011 Pan American games venues in Jalisco, Mexico

How did the games help regional development?

Several sports events were held at sites well away from the Guadalajara metro area. This helped promote a regional profile for the games. The five locations involved (see map) were:

- Puerto Vallarta (beach volleyball, open water swimming, triathlon, sailing)

- Lagos de Moreno (baseball)

- Ciudad Guzmán (rowing, canoeing)

- Chapala (water skiing)

- Tapalpa (mountain biking)

How much did visitors to the games spend?

Local businesses reported sales up 7% during the period of the Games. The total games-related spending by visitors was estimated at $210 million (dollars). Hotel occupancy rates for the period of the games rose from 58.3% in 2010 to 76.4% during the games. The rate was 97% for the 5-star hotels in Guadalajara and Puerto Vallarta.

Even so, according to a local newspaper (The Guadalajara Reporter), local business owners were “underwhelmed” by the Pan American Games’ impact. Restaurants, bars, clubs, taxis and travel agencies all received fewer customers than anticipated. Local business owners said that “very few foreign tourists came for the games, while most spectators at the events were local citizens, athletes and their families, journalists and other games-affiliated personnel.” Business owners in Puerto Vallarta were reported to be “angry at the lack of publicity for the destination”.

Problems with the Athletes Village

The Pan American Athletes Village (Villa Panamericana) was built one kilometer outside Guadalajara’s western ring-road (Periférico) to house all 6,000 participants. The location is conveniently close to the Omnilife Stadium, site of the opening and closing ceremonies.

The Athletes Village has three-bedroom apartments, a central plaza, restaurant, gym, discotheque, chapel, swimming pool, theater and health clinic. The original plan was for the Village apartments to be sold after the Games for between $90,000 and $250,000 (dollars) each. However, the fate of the Athletes Village is still uncertain, because residents of the nearby (and long-established) Rancho Contento subdivision have taken the owners to court, demanding that the Athletes Village be demolished since it has already caused irreparable damage to the local ecosystem.

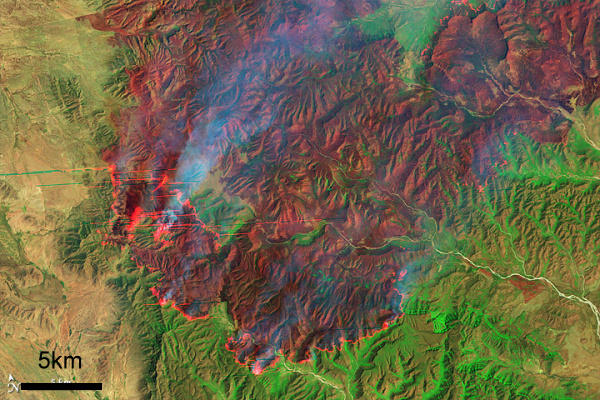

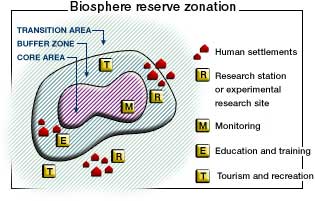

Apart from some issues of housing density in this area, the main concern is that the village has inadequate provision for sewage. After the Games ended, local newspapers reported that faulty treatment plants had resulted in sewage being pumped out of the village on to land inside the nearby Primavera Forest biosphere reserve. Apparently, two of the Village’s treatment plants “collapsed” under the volume of wastewater generated, and partially-treated sewage had collected as open ponds. It is unclear if the sewage contaminated local subsoil and streams. After the Games, city officials closed the plants and fined the Athletes Village administrators. The administrators claim that the plants and Village had been designed to accommodate only 2500 to 3000 athletes, not the 6000 participants that were later housed there.

Conclusion

The lasting legacy of the games is a number of new hotels in Guadalajara, including hotels in the Westin and Riu chains, and a number of new or upgraded sports venues. In addition, many roads were repaved and numerous other beautification projects have helped improve Guadalajara’s urban fabric and infrastructure. The city’s main exhibition space (Expo Guadalajara) and the international airport have both been expanded.

The first obvious benefit of these improvements has been that the city (and its new Aquatics Center) have been chosen to host the 2017 World Swimming Championships.

Related posts:

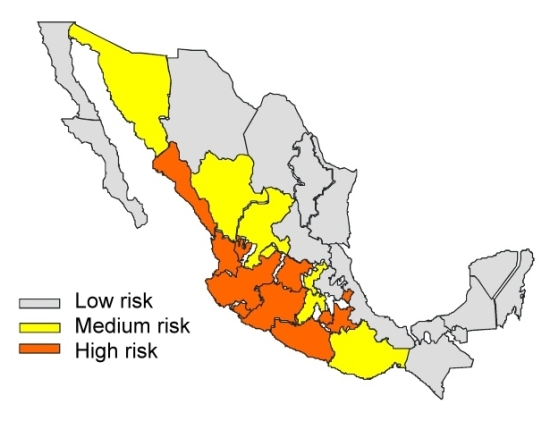

Altitudes in this region vary from a few hundred to several thousand meters. The principal peaks are shown on the map. They include many of Mexico’s most famous mountains, such as Popocatepetl and Iztaccihuatl, near Mexico City; Pico de Orizaba, Mexico’s highest peak; Paricutín, the only completely new volcano in the Americas in recent times; and Colima, considered the most active at present. Many of the volcanoes are surprisingly young. For instance, a study using Carbon‑14 dating on the palaeosols (ancient soils) under 12 volcanoes in the Toluca area yielded ages ranging from 38,600 to 8400 years before present.

Altitudes in this region vary from a few hundred to several thousand meters. The principal peaks are shown on the map. They include many of Mexico’s most famous mountains, such as Popocatepetl and Iztaccihuatl, near Mexico City; Pico de Orizaba, Mexico’s highest peak; Paricutín, the only completely new volcano in the Americas in recent times; and Colima, considered the most active at present. Many of the volcanoes are surprisingly young. For instance, a study using Carbon‑14 dating on the palaeosols (ancient soils) under 12 volcanoes in the Toluca area yielded ages ranging from 38,600 to 8400 years before present.

Click for printable pdf map

Click for printable pdf map