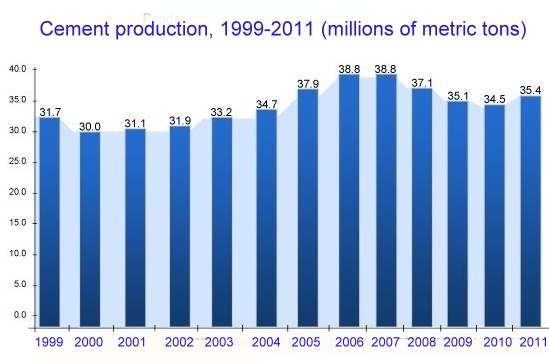

In 2011, Mexico produced 35.4 million tons of cement, 3% more than a year earlier. The first cement-making plant was built in Mexico in 1906, a few years after cement was first officially approved for use in the construction sector. Cement demand grew only slowly prior to a spate of public infrastructure projects in the mid 1940s.

There are currently six major cement makers in Mexico. About 20% of production is sold in bulk to large construction companies. The remaining 80% of production is sold in 50-kg bags, used either by formal residential construction firms (50% of the total) or in informal (do-it-yourself) projects (32% of all purchases).

Cemex holds a 49% share of the domestic market, followed by Holcim Apasco (21%), Cruz Azul (16%), Cementos Moctezuma (10%). The remaining 4% is split between Cementos Chihuahua and Lafarge Cementos. A seventh company, Cementos Fortaleza (part-owned by Carlos Slim, the world’s richest man), is due to open early next year.

Cemex, based in Monterrey, is one of Mexico’s most important multinational companies. It is the world’s third largest cement producer and distributor, with operations in fifty countries worldwide. In 2004 Cemex received the Wharton Infosys Business Transformation Award for its creative and efficient use of information technology. Before Cemex, who had ever heard of cement mixers, armed with GPS devices, satellite links and computer systems hooked up via satellite links to the parent company’s HQ, cruising cities? The strategy allowed the company to achieve enviable levels of operating efficiency while meeting demanding delivery deadlines even in congested urban areas such as Mexico City.

China leads the world in terms of the volume of cement production, making around 2,000 million metric tons (mmt) a year, followed by India (710 mmt), Iran (72), USA (68), Turkey (64), Brazil (63) and Russia (52). Mexico (35.4) places 15th on the list, behind Japan, South Korea, Egypt and Thailand, but ahead of Germany, Indonesia, France, Canada, the UK and Spain.

On a per person basis, annual cement consumption in Mexico is about 300 kg/person, well below the levels recorded in the USA (1100 kg) and elsewhere. (The extreme cement consumer in recent years has been Dubai, with the staggering figure of 8000 kg/person!) Cement production may be a good indicator of how much construction is taking place, but is not very good news for the environment and climate change, since high quantities of carbon dioxide are released into the atmosphere during the production process. Globally, cement making is responsible for up to 10% of people’s total carbon dioxide emissions each year.

The carbon dioxide comes from three distinct sources:

- During the conversion of raw materials into clinker

- From the combustion of fuels needed in the cement kilns

- Indirectly, from producing the energy required to power production machinery such as grinders and electric motors.

However, according to the Center for Clean Air Policy’s Sector-based Approaches Case Study: Mexico,

“Mexico’s cement industry is among the most modern and efficient in the world today. All the 50-plus kilns operating in the country’s 34 cement plants are dry-process. Mexico’s cement manufacturers are also using energy efficiency enhancing technologies such as preheaters and precalciners in many of their facilities. Moreover, a number of plants make use of some forms of low carbon alternative fuels.”

“Between 1992 and 2003, emissions of CO2 by the cement industry in Mexico increased roughly 25%. This compares with a nearly 108% increase in cement sector emissions from all developing countries during that same time frame and a 34% increase in U.S. cement industry emissions. The relatively slow growth of emissions from Mexico’s cement sector is an indication of the high overall efficiency of the sector.”

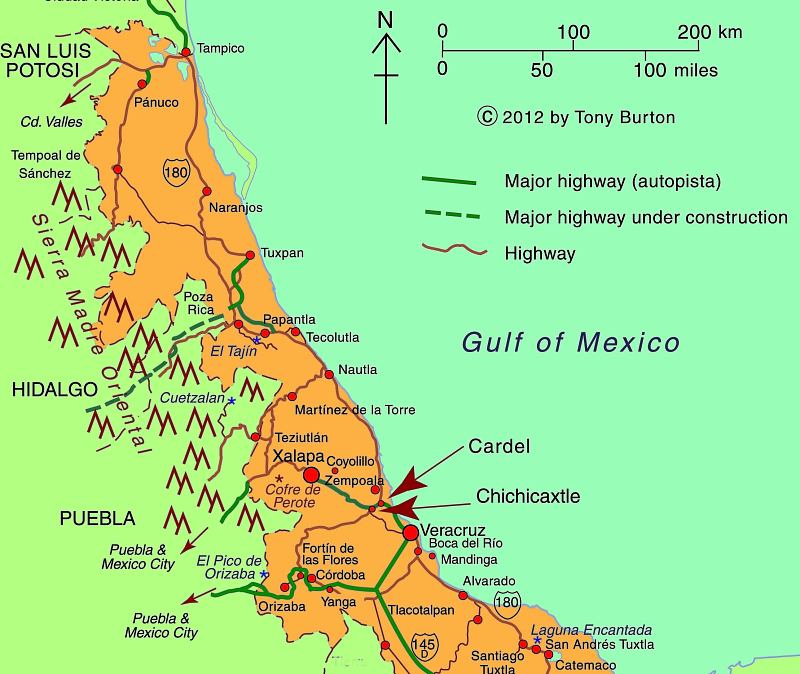

A future post will look at the location of cement plants in Mexico.

![birds-ibas-2 Important Bird Areas in Mexico [Birdlife.org]](http://geo-mexico.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/birds-ibas-2.jpg)