The Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP), together with an international committee of transportation and development experts, has awarded Mexico City the 2013 Sustainable Transport Award.

The Institute for Transportation and Development Policy works with cities worldwide to bring about sustainable transport solutions that cut greenhouse gas emissions, reduce poverty, increase urban mobility and improve the quality of urban life.

The 2013 Sustainable Transport Award recognizes Mexico City’s Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system, cycling and walking infrastructure, parking program, and revitalization of public space. Established in 2005, the Sustainable Transport Award recognizes leadership and visionary achievements in sustainable transportation and urban livability, and is presented to a city each January for achievements in the preceding year.

The Sustainable Transport Award was presented to Mexico City on January 15, 2013 at an awards ceremony during the annual meeting of the Transportation Research Board, one of six major divisions of the U.S. National Research Council. ITDP board president and former Mayor of Bogotá Enrique Peñalosa presented Mexico’s Minister of Transport, Rufino León, and Minister of Environment, Tanya Muller with the award. The former Mayor of Mexico City, Marcelo Ebrard, who oversaw much of Mexico City’s sustainable transport projects, made closing remarks at the ceremony. Janette Sadik-Khan, Commissioner of the New York City Department of Transportation, delivered the keynote address.

Mexico City has implemented many projects in 2012 that have improved livability, mobility, and quality of life for its citizens, making the Mexican Capital a best practice for Latin America.

- The city expanded its Bus Rapid Transit system, Metrobús, with Line 4, running along a corridor from the historic center of the city to the airport.

- The city piloted a comprehensive on-street metered parking program, EcoParq.

- The city opened line 12 of its Metro system (Sistema de Transporte Colectivo Metro).

- The city expanded its successful public bike system Ecobici, and added new bike routes (ciclovías).

- The city revitalized public spaces including the Alameda Central and Plaza Tlaxcoaque.

The finalists and winner were chosen by a Committee that includes the most respected experts and organizations working internationally on sustainable transportation. The Committee includes the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, The World Resources Institute Center for Sustainable Transport, GIZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit), Clean Air Asia, Clean Air Institute, United Nations Centre for Regional Development (UNCRD), Transport Research Laboratory, EcoMobility, Local Governments for Sustainability (ICLEI) and the Transport Research Board’s Transportation in the Developing Countries Committee.

“Mexico City was like a patient sick with heart disease, its streets were some of the most congested in the world”, says Walter Hook, CEO of ITDP, “In the last year, Mexico City extended its great Metrobus BRT system straight through the narrow congested streets of its spectacular historical core, rebuilt public parks and plazas, expanded bike sharing and bike lanes, and pedestrianized streets. With the blood flowing again, Mexico City’s urban core has been transformed from a forgotten, crime ridden neighborhood into a vital part of Mexico City’s future.”

“We congratulate the Federal District of Mexico for their leadership in advancing sustainable transport. Celebrating success is a way to highlight best practices; many cities will find inspiration in your great achievements.”

“Sustainable transport systems go hand in hand with low emissions development and livable cities. Mexico City’s success has proven that developing cities can achieve this, and we expect many Asian cities to follow suit,” says Sophie Punte, Executive Director of Clear Air Asia.

Past winners of the Sustainable Transport Award include: Medellín, Colombia and San Francisco, United States (2012); Guangzhou, China (2011); Ahmedabad, India (2010); New York City, USA (2009); London, UK (2008); Paris, France (2008); Guayaquil, Ecuador (2007); Seoul, South Korea (2006), and Bogotá, Colombia (2005).

[Note: This post is based on the text of a press release from the The Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP)]

Related posts:

- The challenge of building and maintaining Mexico City’s metro system [Nov 2010]

- Mexico City’s Ecobici cycle rental system enters its second year [Feb 2011]

- The on-going transformation of Mexico City [May 2011]

- The revitalization of Mexico City’s historic downtown core [Aug 2010]

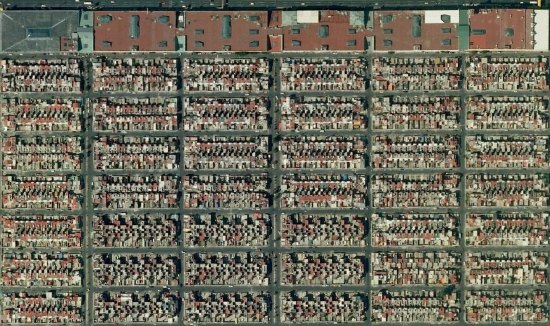

- Traffic congestion still a serious problem for commuters in Mexico City [Sep 2011]

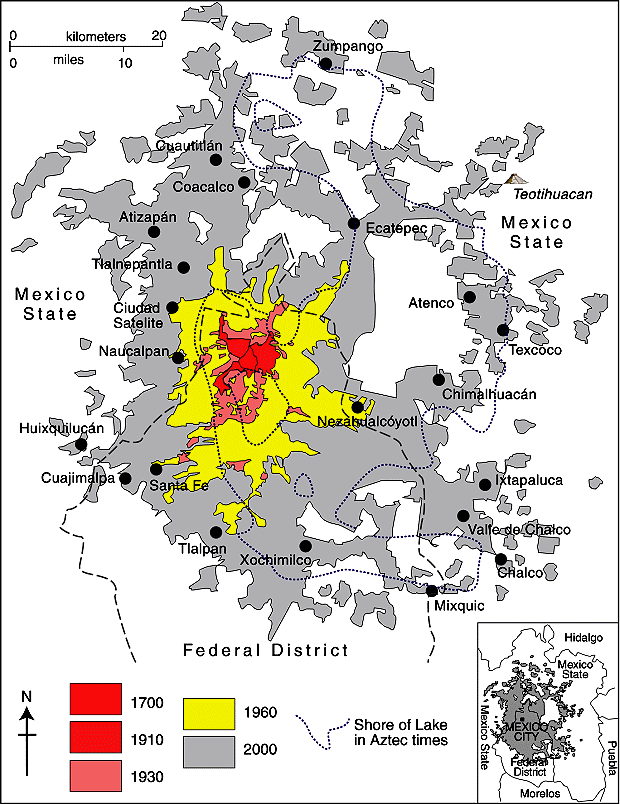

- Mexico City tackles the challenges of population, commuting and air quality [Aug 2012]

- The Eastern Drainage Tunnel: a solution to Mexico City’s drainage problems?

- Why are some parts of Mexico City sinking into the old lakebed?

- How fast is the ground sinking in Mexico City and what can be done about it?