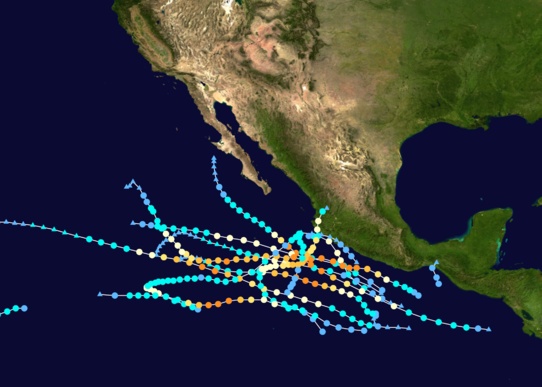

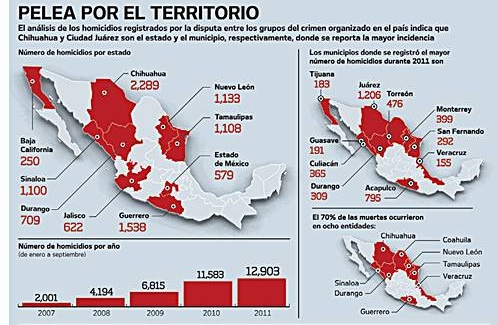

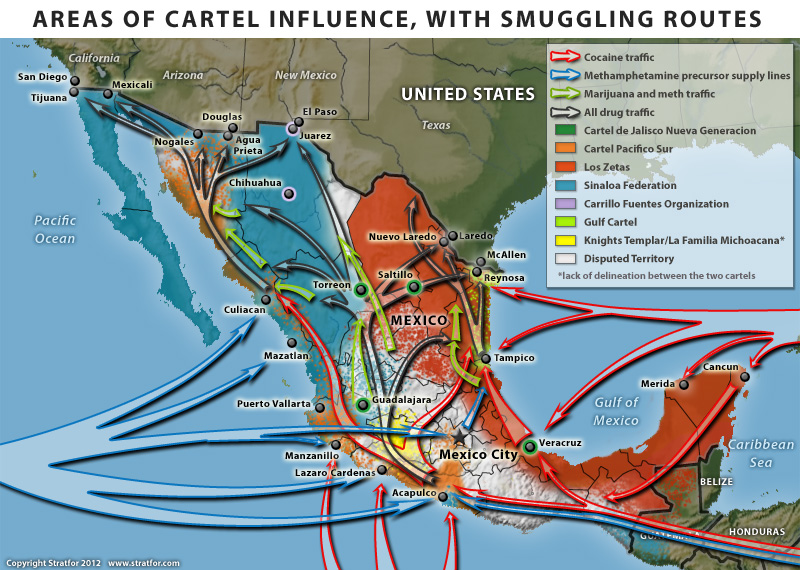

It is becoming harder and harder to keep up with the ever-changing landscape of drug cartel territories. As the government crack-down leads to more and more high-profile arrests, some cartels are struggling to reorganize and lose ground (literally) as rival groups step in to take control. This has resulted in drug-related violence in the past year spreading to new areas, accounting for the serious incidents reported in cities such as Guadalajara and Acapulco and in several parts of the state of Veracruz, even as violence diminishes in some areas where it was previously common. (The patterns of drug-related violence are analyzed in depth in several other posts tagged “drugs” on this site).

Who are the main players? (February 2012)

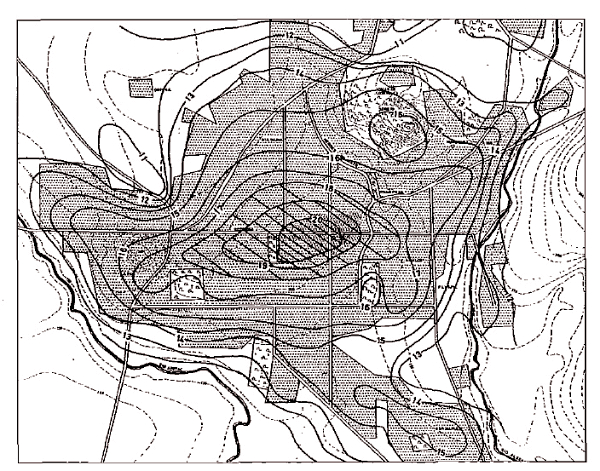

According to security analysts Stratfor in their report entitled Polarization and Sustained Violence in Mexico’s Cartel War, polarization is under way among Mexico’s cartels. Smaller groups have been subsumed into either the Sinaloa Federation, which controls much of western Mexico, or Los Zetas, which controls much of eastern Mexico.

The major cartels are:

- Los Zetas, now operating in 17 states, control more territory than the Sinaloa Federation, and are more prone to extreme violence. They control much of eastern Mexico.

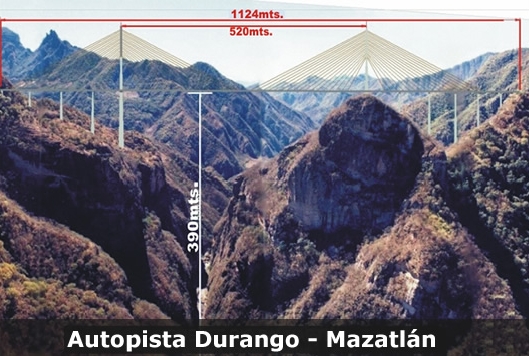

- Sinaloa Federation, formerly the largest cartel, currently in control of most of western Mexico. They have virtually encircled the Juárez Cartel in Cd. Juárez. Their production of methamphetamine has been disrupted by numerous significant seizures of precursor chemicals in west coast ports, including Los Mochis and Mazatlán (Sinaloa), Manzanillo (Colima), Puerto Vallarta (Jalisco) and Lázaro Cárdenas (Michoacán). As a result, the Sinaloa Federation appears to have moved some of its methamphetamine production to Guatemala.

- Juárez Cartel, now largely limited to Cd. Juárez

- Tijuana Cartel, now dismantled and effectively a subsidiary of the Sinaloa Federation

- Cartel del Pacífico Sur; weak, and competing with Zetas in central Mexico states of Guerrero and Michoacán

- Gulf Cartel, which still has important presence along Gulf coast, but weakened due to infighting and conflicts with Los Zetas.

- Knights Templar (Los Caballeros Templarios) comprises remnants of La Familia Michoacana (LFM), which is now almost defunct. Other former LFM members joined the Zetas.

- Independent Cartel of Acapulco is small and apparently weakened.

Alongside these cartels, three “enforcer” groups of organized assassins have arisen: the Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación (enforcers for the Sinaloa Cartel), La Resistencia (Los Caballeros Templarios) and La Mano con Ojos (Beltrán Leyva).

Turf wars

Drug violence is largely concentrated in areas of conflict between competing cartels. The major trouble spots are Tamaulipas (Gulf Cartel and Zetas); the states of Durango, Coahuila, Zacatecas and San Luis Potosí (Sinaloa Cartel and Zetas); Chihuahua (Juarez Cartel and Sinaloa Cartel); Morelos, Guerrero, Michoacán and State of México (Cartel del Pacífico Sur, aided by Zetas, against Los Caballeros Templarios).

One possible strategy (for the government) would be to stamp out all smaller groups until a single major group controled almost all the trade in drugs. At this point, so the argument goes, incidental violence against third parties would drop dramatically. Such a simplistic approach, however, fails to tackle the economic, political and social roots of narco-trafficking.

Meanwhile, there are some signs that Los Caballeros Templarios, the breakaway faction of LFM, based in the western state of Michoacán, wants to transform itself into a social movement. This is presumably why it has distributed booklets in the region claiming it is fighting a war against poverty, tyranny and injustice.

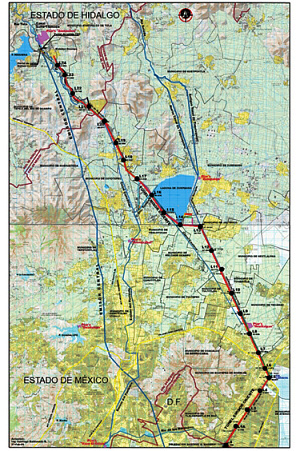

Click for printable pdf map

Click for printable pdf map