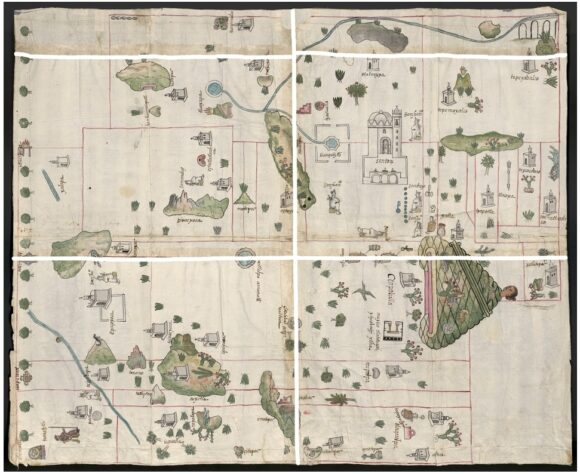

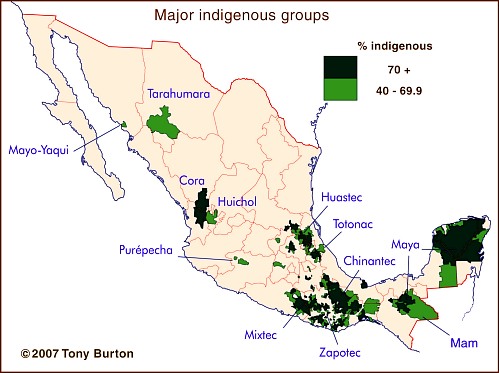

The Lacondon Maya are one of the most isolated and culturally conservative of Mexico’s numerous indigenous peoples. Their homeland is in the remote Lacondon Jungle in eastern Chiapas, close to the Guatemalan border. The Lacondon were the only Mayan people not conquered or converted by the Spanish during the colonial era. Until the mid-20th century they had little contact with the outside world, while maintaining a sustainable agricultural system and practising ancient Mayan customs and religion.

This short two-part video by Joel Kimmel (Part One above; Part Two below) briefly traces the history of the Lacandon back to the classic Mayan civilization. The videos document their successful, slash and burn, rotating, multicrop, subsistence agricultural lifestyle, steeped in religious ritual, and sustained over centuries in small isolated groups in the almost impenetrable Lacandon jungle.

The film then looks at the more recent outside influences that resulted in the near extinction of the Lacandon by the mid 20th century. Today their population has increased again and is estimated at between 650 and 1000, living in about a dozen villages. The second video focuses on the Lacondon’s confrontation with the modern world over the past four decades. One group, the “southern” Lacandon have opted for Christianity and the trappings of modern life, whilst some in the “northern” group, centered around the village of Naja, near the Mayan ruins of Palenque, attempt to maintain the old customs and religion. The video ends with the thoughts of a former Director of Development at Na Bolom, regarding the possibility, and immense difficulty, of trying to preserve what remains of their language, cultural heritage and ecological knowledge, treasures the world can ill afford to lose.

The videos introduce speakers and photos from the internationally famous Casa Na Bolom, in San Cristóbal de la Casas, Chiapas. This scientific and cultural research institute was founded in 1951 by Danish archeologist Franz Blom and his Swiss wife, Trudy Blom, journalist, photographer and later environmental activist. They devoted their lives to documenting the cultural history of the Lacondon people and life in the Chiapas jungle and advocating for the survival of both. Following Trudy Blom’s death in 1993, the Asociación Cultural Na Bolom has continued to operate the center as a museum, research and advocacy center, and tourist hotel. It houses an archive of over 50,000 photographs, and other documentation created by scholars over the decades.

The two videos provide visual proof of the forces of modern Mexico that have threatened the existence of the Lacondon way of life – government roads opening up the jungle to loggers and other settlers, logging permits resulting in massive clearcutting of the mahogany forests , the arrival of tourism, Coca-Cola and canned foods, mainstream education and modern technology like satellite television.

Not covered in the video is the fact that a Mexican presidential order in 1971 granted 614,000 acres to the Lacandon Community, recognizing their land rights over the, by then, more numerous settlers who had been allowed to colonize the Lacandon Forest under previous governments. This, however, has brought the Lacandon into conflict with many settler-groups, creating problems which continue to the present time. (See Chiapas Conflict on Wikipedia).

Related posts

- The geography of languages in Mexico: Spanish and 62 indigenous languages

- The geography of the Maya: does central place theory apply to ancient Maya settlements?

- Chiapas: carbon capture program or indigenous people?

- Resistance to government-sponsored change in Chiapas, Mexico

- Organic farming helps the Mam of Chiapas regain their cultural identity