Tequila is made by distilling the juice of certain species of agave plants. Agaves are commonly called “century plants” in the USA, a name derived from the length of time they supposedly grow before producing a flowering stalk – actually, from eight to twenty years depending on the species, rather than the hundred suggested by their common name! Some species flower only once and die shortly afterwards, others can flower almost every year. Agaves are no relation botanically to cacti, even though they are often mistakenly associated with them. The ideal agave for tequila is the Agave tequilana Weber azul which has bluish-colored leaves.

Agave field in Jalisco. Photo: Tony Burton

The tequila agaves are started from seed or from onion-size cuttings. When the plants are mature (about 10 years later), their branches are cut off, using a long-handled knife called a coa, leaving the cabeza (or “pineapple”), which is the part used for juice extraction. Cabezas (which weigh from 10 to 120 kilos) are cut in half, and then baked in stone furnaces or stainless steel autoclaves for one to three days to convert their starches into sugars.

From the ovens, the now golden-brown cabezas are shredded and placed in mills which extract the juices or mosto. The mixture is allowed to ferment for several days, then two distillations are performed to extract the almost colorless white or silver tequila. The spirit’s taste depends principally on the length of fermentation. Amber (reposado) tequila results from storage in ex-brandy or wine casks made of white oak for at least two months, while golden, aged (añejo) tequila is stored in casks for at least a year, and extra-aged (extra añejo) for at least three years.

Distillation: the Filipino Connection

Mexico’s indigenous Indians knew how to produce several different drinks from agave plants, but their techniques did not include distillation, and hence, strictly speaking, they did not produce tequila. Fermented agave juice or pulque may be the oldest alcoholic drink on the continent; it is referred to in an archival Olmec text which claims that it serves as a “delight for the gods and priests”. Pulque was fermented, but not distilled.

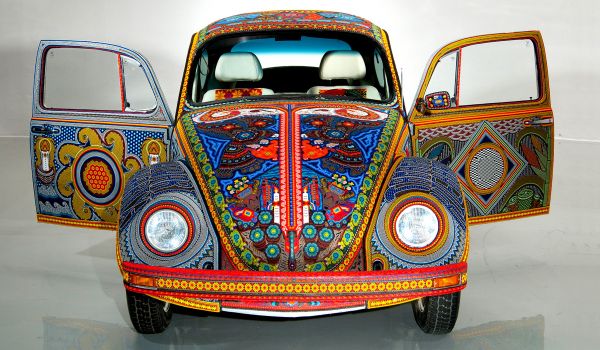

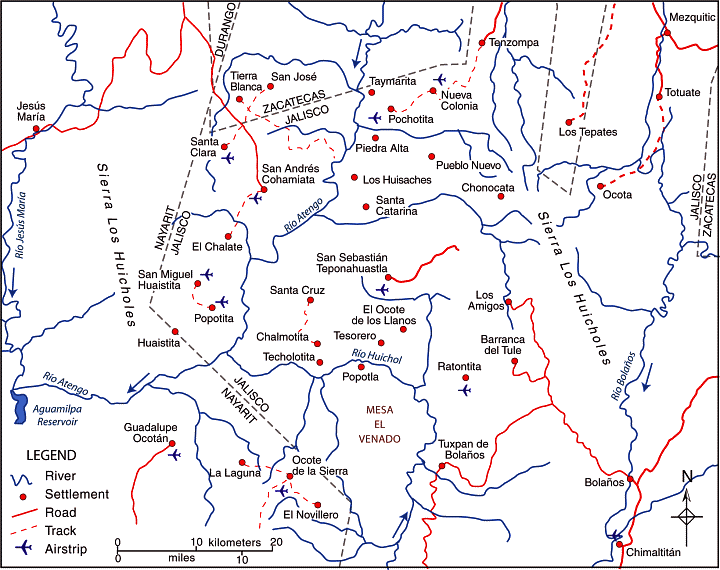

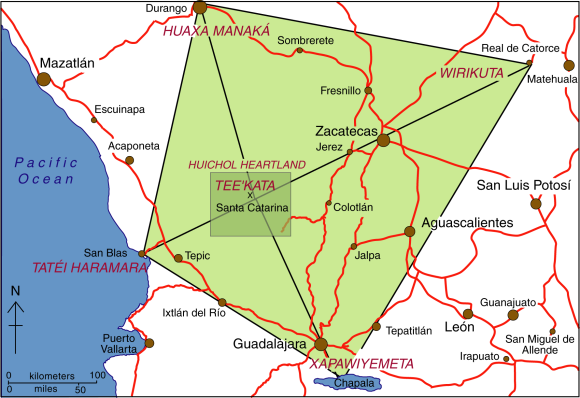

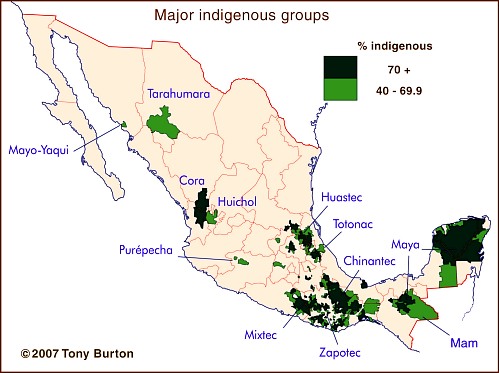

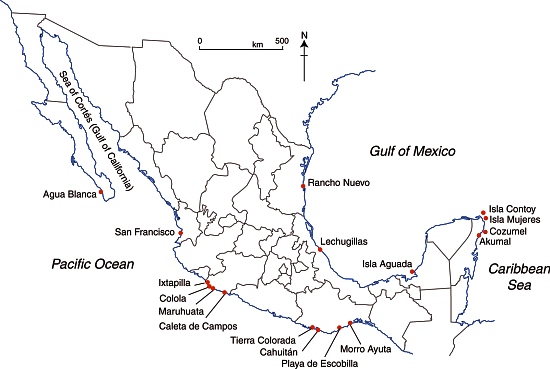

If the indigenous peoples didn’t have distilled agave drinks, then how, when and where did distillation of agave first occur? In 1897, Carl Lumholtz, the famous Norwegian ethnologist, who spent several years living with remote Indian tribes in Mexico, found that the Huichol Indians in eastern Nayarit distilled agave juice using simple stills, but with pots which seemed to be quite unlike anything Spanish or pre-Columbian in origin.

By 1944, Henry Bruman, a University of California geographer, had documented how Filipino seamen on the Manila Galleon had brought similar stills to western Mexico, for making coconut brandy, during the late sixteenth century.

Dr. Nyle Walton, of the University of Florida, expanded on Bruman’s work, showing how the Spanish authorities had sought to suppress Mexican liquor production because it threatened to compete with Spanish brandy. This suppression led to the establishment of illicit distilling in many remote areas including parts of Colima and Jalisco. Even today, the word “tuba”, which means “coconut wine” in the Filipino Tagalog language, is used in Jalisco for mezcal wine before it is distilled for tequila. This is probably because the first stills used for mezcal distillation were Filipino in origin.

“Appelacion Controlée”

Though colonial authorities tried to suppress illegal liquors, the industry of illicit distilling clearly thrived. One eighteenth century source lists more than 81 different mixtures, including some truly fearsome-sounding concoctions such as “cock’s eye”, “rabbit’s blood”, “bone-breaker” and “excommunication”! By the 1670s, the authorities saw the wisdom of taxing, rather than prohibiting, liquor production.

For centuries, distilled agave juice was known as mezcal or vino de mezcal “mezcal wine”). It is believed that the first foreigner to sample it was a Spanish medic, Gerónimo Hernández, in the year 1651. The original method for producing mezcal used clay ovens and pots.

By the end of the nineteenth century, as the railroads expanded, the reputation of Tequila spread further afield; this is when the vino de mezcal produced in Tequila became so popular that people began calling it simply “tequila”. When the Mexican Revolution began in 1910, it swept away a preference for everything European and brought nationally-made tequila to the fore. Tequila quickly became Mexico’s national drink. It gained prominence north of the border during the second world war, when the USA could no longer enjoy a guaranteed supply of European liquors.

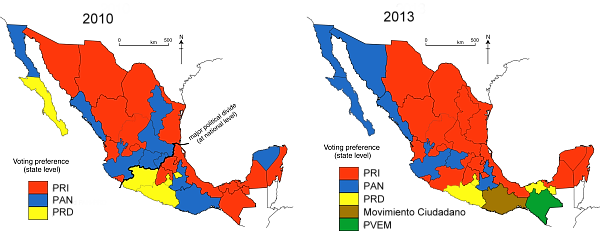

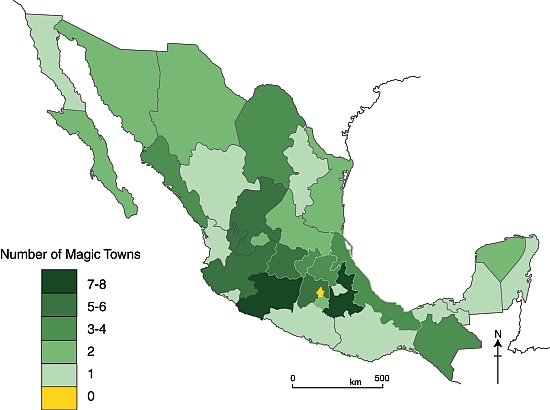

To qualify as genuine tequila, the drink has to be made in the state of Jalisco or in certain specific areas of the states of Nayarit, Guanajuato, Michoacán and Tamaulipas. (We will take a closer look at this distribution in a future post).

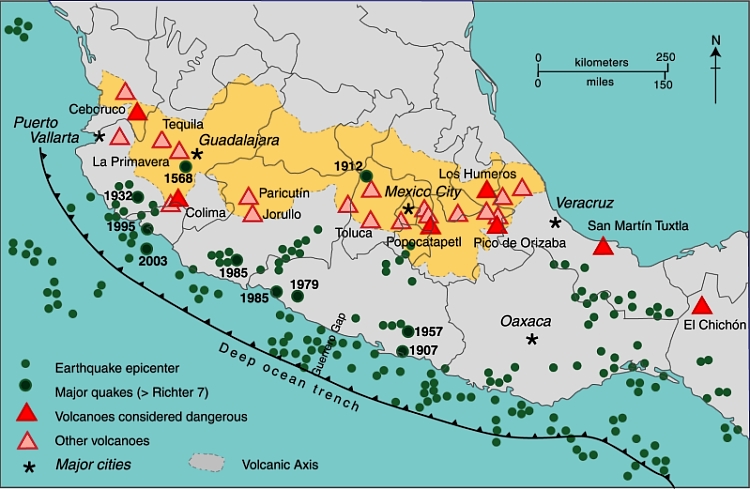

The ideal growing conditions are found in semiarid areas where temperatures average about 20 degrees Centigrade, with little variation, and where rainfall averages 1000 mm/yr. In Jalisco, this means that areas at an elevation of about 1,500 meters above sea level are favored. Agaves prefer well-drained soils such as the permeable loams derived from the iron-rich volcanic rocks in Mexico’s Volcanic Axis.

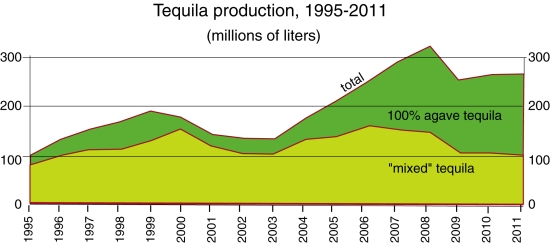

Production of tequila has tripled within the last 15 years to about 250 million liters a year (2010). About 65% of this quantity is exported. Almost 80% of exports are to the USA, with most of the remainder destined for Canada and Europe.

Connoisseurs argue long and loud as to which is the better product, but all agree that the best of the best is made from 100% Agave tequilana Weber azul. I’m no connoisseur, but my personal favorite is Tequila Herradura, manufactured in Amatitán, a town between Tequila and Guadalajara. Anyone interested in the history of tequila will enjoy a visit to Herradura’s old hacienda “San José del Refugio” in Amatitán, where tequila has been made for well over a century. The factory is a working museum with mule-operated mills, and primitive distillation ovens, fueled by the bagasse of the maguey. The Great House is classic in style, with a wide entrance stairway and a first floor balustrade the full width of the building.

Visitors to the town of Tequila, with its National Tequila Museum, can enter any one of several tequila factories to watch the processing and taste a sample. They can also admire one of the few public monuments to liquor anywhere in the world – a fountain which has water emerging from a stone bottle supported in an agave plant. “Tequila tourism” is growing in popularity. Special trains, such as “The Tequila Express” run on weekends from the nearby city of Guadalajara to Amatitán, and regular bus tours visit the growing areas and tequila distilleries. The town of Tequila holds an annual Tequila Fair during the first half of December to celebrate its famous beverage. Another good time to visit is on 24 July, National Tequila Day in the USA.

In 2006, UNESCO awarded World Heritage status to the agave landscape and old tequila-making facilities in Amatitán, Arenal and Tequila (Jalisco).

Related posts:

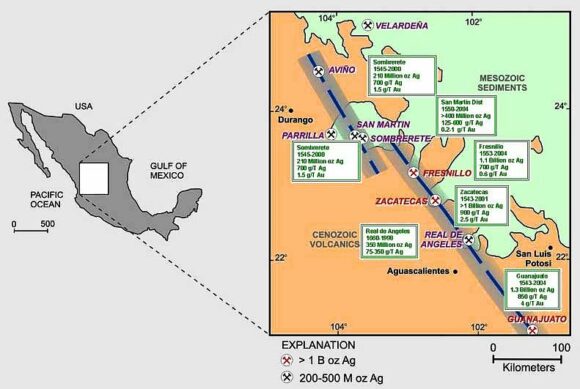

Fresnillo is still an important mining center today. Fresnillo plc, incorporated in the UK, is Mexico’s largest single silver mining company and the country’s second largest gold producer. It operates mines in three major mining zones in Mexico—Fresnillo (Zacatecas), Ciénega (Durango) and Herradura (Sonora)—and is actively developing or exploring numerous other sites.

Fresnillo is still an important mining center today. Fresnillo plc, incorporated in the UK, is Mexico’s largest single silver mining company and the country’s second largest gold producer. It operates mines in three major mining zones in Mexico—Fresnillo (Zacatecas), Ciénega (Durango) and Herradura (Sonora)—and is actively developing or exploring numerous other sites.