The Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) has published its Mexico Peace Index. The following excerpts come from the Executive Summary of the Mexico Peace Index Report 2015:

The Mexico Peace Index provides a comprehensive measure of peacefulness in Mexico from 2003 to 2014. The 2015 report aims to deepen the understanding of the trends, patterns and drivers of peace in Mexico while highlighting the important economic benefits that will flow from a more peaceful society.

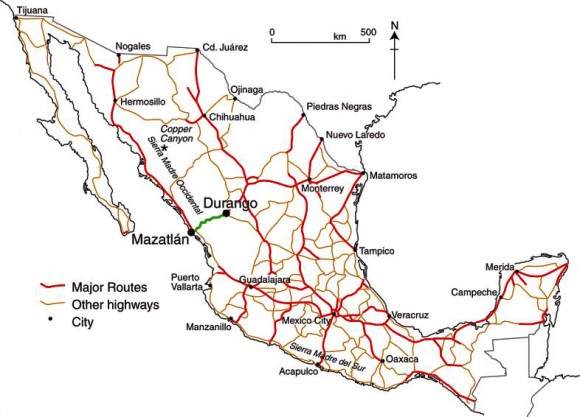

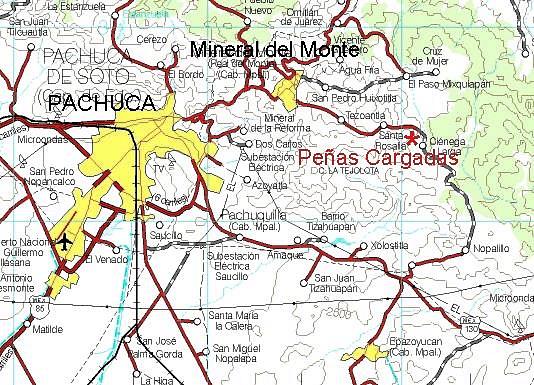

Mexico Peace Index, 2015. Credit: Institute for Economics and Peace.

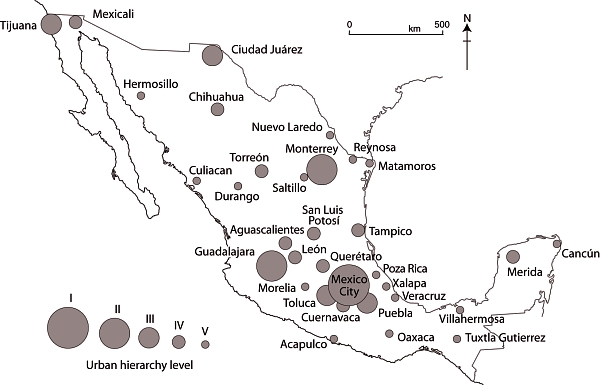

The map above shows the relative values of the MPI by state, where dark blue means the most peaceful states and dark red the least peaceful (most violent) states.

Improvement since 2012

According to the report, Mexico’s peace has improved 10.5% since 2012, continuing the trend from 2011; however, 2014 saw very little improvement, improving only 0.7%. It is too early to determine whether this is a new trend. Mexico’s level of peace in 2014 approached 2007 levels, when homicide and violent crime began to increase rapidly.

The MPI indicators registering the largest improvements in the last two years were the homicide rate, which fell by 30%, and the level of organized crime, which improved by 25%. All three measures in the organized crime indicator (extortion, kidnapping and narcotics offenses) improved. There was also a significant reduction in the violent crime rate, which fell by 12%.

Furthermore, the recorded increase in peacefulness was widespread. In the last two years, 26 out of the 32 states saw improvements in peacefulness, with all of them recording reductions in the violent crime rate and 23 states recording reductions in the homicide rate. The biggest improvements were recorded in the least peaceful states; contrary to the overall trend, the most peaceful states became slightly less peaceful. These diverging trends resulted in a substantial narrowing of the gap between the least peaceful and the most peaceful states.

In contrast, during the same two-year period, weapons crime increased significantly and was up by 11%. The three other indicators that make up the MPI (justice efficiency, incarceration and police funding) have plateaued or slightly deteriorated and are now at record highs.

The justice efficiency indicator continued to decline, which is very concerning, with the number of homicides relative to the number of prosecutions doubling from 1.45 in 2006 to 3.43 in 2013. The justice efficiency indicator measures the ratio of homicide convictions to homicides in a given year and is used as a proxy for impunity.

Additionally, the rate at which people were sentenced to prison fell from 210 per 100,000 people to 104 from 2003 to 2014. Combined with the deterioration in the justice efficiency indicator, this is a troubling trend that highlights the urgent need to fully implement the current justice reforms.

It should be noted that the declines in homicides and gang-related violence do not necessarily mean that criminal organizations are less powerful; they may have become more circumspect in their activities. This reflects a paradox in Mexico: while indicators of peacefulness have greatly improved in the last four years, many Mexicans still report high perceptions of criminality. Additionally, officially recorded rates of homicide and violent crime are still very high by global standards.

Under-reporting of violent crime and other criminal activities is a serious issue in Mexico, with IEP estimating that rape is reported only eight percent of the time and assault only 23%. To create a more accurate index, IEP has adjusted all indicators for under-reporting rates.

For many, these concerns create doubt about the reliability of criminal justice statistics. To determine the veracity of the official data, IEP compared various alternative datasets and victimization surveys against the official data. The results tend to support the trend towards higher levels of peace, but with some qualifications.

Main findings of the Mexico Peace Index 2015

- Mexico has experienced a large decrease in violence since 2011, with the national level of peace improving by 16%.

- Progress in peace plateaued last year; it is too early to determine if this is the start of a new trend.

- The level of peace as measured by the 2015 MPI is still 18% lower than in 2003.

- The most peaceful state in Mexico is Hidalgo, followed by Yucatán, Querétaro, Campeche, Tlaxcala and Chiapas.

- Of the 76 largest metropolitan areas of Mexico, the most peaceful is Orizaba in Veracruz, and the least peaceful is Culiacán in Sinaloa.

- The eastern region remains the most peaceful in Mexico, while the northern region is still the most violent, although the gap between the north and the other regions is now at its lowest point since 2004.

Trends in Peace

Peace improved in the majority of states in Mexico in the last two years, with 26 out of 32 states improving. The largest improvements were in the northern region, which improved 17.8%. The gap in the levels of peace between the least and most peaceful states is now at its lowest point since 2006.

Over the last two years, the largest decreases in violence have been in the homicide rate, which fell almost 30%, and the level of organized crime, which fell by 25%.

The only indicator that recorded a significant deterioration in the last two years is weapons crime, which increased by 11%. The police funding indicator and the justice efficiency indicator recorded very slight deteriorations, reaching their worst levels in 2014.

The fall in the homicide rate is mainly due to a reduction in homicides related to organized crime, as the biggest reductions were recorded in the states with the worst levels of drug cartel activity.

While there is some doubt about the accuracy of government crime statistics, multiple data sources do support a decline in the homicide rate over the last two years. This strongly suggests the progress in peace is real.

On an international comparison, Mexico fell 45 places in the Global Peace Index between 2008 and 2013. It remains the least peaceful country in Central America and the Caribbean.

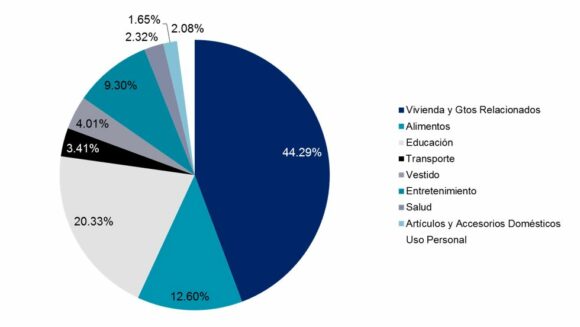

Economic Value of Peace in Mexico

The total economic impact of violence in Mexico in 2014 is estimated to be $3 trillion pesos or US$233 billion, equivalent to 17.3% of GDP. This represents $24,844 pesos, or almost US$1,946, per citizen. This is a 16.7% decrease from 2012, when the total economic impact of violence in Mexico was $3.57 trillion pesos.

The states with the highest per capita economic impact from violence are Guerrero, Morelos, Baja California and Tamaulipas, with the economic impact in Guerrero at $43,666 pesos/person. If the 16 least peaceful states in 2003 had experienced the same economic growth as the 16 most peaceful states in 2003, then the Mexican economy in 2014 would be $140 billion pesos or 13% larger.

Related posts: