As presented in a previous post, 2.8% of Mexicans (3.3 million) live in severe poverty based on a June 2014 Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) developed by the Oxford (University) Poverty & Human Development Initiative (OPHI)[1]. The previous post explained the MPI measure of poverty and discussed how Mexico compared to the 108 countries in the study. This post looks into the details of MPI poverty within Mexico. Poverty in Mexico is mostly a rural problem. According to the study, roughly 8.5% of rural residents are severely poor (2.3 million) compared to only 1.1% of people in urban areas (1.0 million).

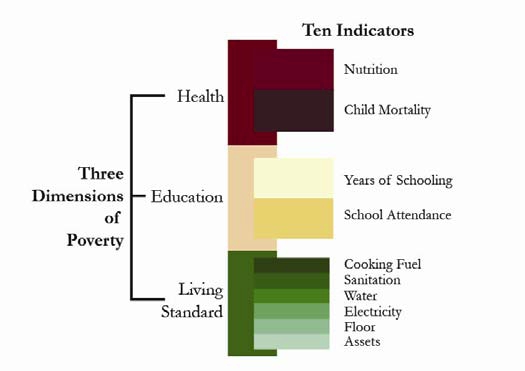

As indicated in the previous post, the MPI is based on ten separate indicators; two for education, two for health and six for standard of living. In all cases, people in urban areas scored better on all the indicators than those in rural areas. In rural areas several key MPI indicators contribute the most to poverty: insufficient schooling (19.3%), malnutrition (14.1%), children not attending school (12.9%), use of an unhealthy cooking fuel (12.9%) and unacceptable sanitation (11.7%) [2].

As expected the poorer more rural southern states had the highest MPI poverty levels. Oaxaca had the most living in poverty (11.1%) followed by Guerrero (10.6%) and Chiapas (8.3). Poverty was also high in San Luis Potosí (6.7%), Puebla (5.3%), Veracruz (4.6%), Campeche (4.2%), and Hidalgo (3.4%). These states all have significant indigenous populations. Though the study did not access severe poverty among indigenous groups, available information suggests that those groups suffer by far the highest levels of severe poverty. States with lowest MPI levels are Nuevo León (0.2%), Federal District (0.4%), Baja California (0.4%), Baja California Sur (0.4%), Durango (0.7%), Morelos (1.0%), Colima (1.0%), and Aguascalientes (1.0%); all states with relatively few indigenous inhabitants.

References:

[1] Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), “Global MPI Data Tables for 2014”, Oxford University, June 2014.

[2] Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), “OPHI Country Briefing 2014: Mexico,”

Related posts:

- Multidimensional Poverty in Mexico: How severe is poverty in Mexico? (Jul 2014)

- Extreme poverty declined between 2010 and 2012 (Feb 2014)

- Poverty on the rise in some states in Mexico (Jan 2014)

- Trends in income distribution in Mexico: are the poor getting poorer? (Feb 2011)

- The measurement of poverty: the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) (Sep 2011)