Linked to Mother’s Day [10 May in Mexico], Save the Children just published their 13th annual report on the“State of the World’s Mothers”.

The report investigates childhood malnutrition and relates it to the well-being of mothers. The focus is on the first 1,000 days from the time of conception to the child’s second birthday. Proper nutrition and health care during these 1,000 days are critically important to brain development and the welfare of the child throughout its lifetime.

Mother and child in a Mexican market. Photo: Tony Burton.

For decades, development experts have recognized that health, education and economic opportunity of mothers are crucially important to the quality of life of their children. Mothers’ level of education is often the most important factor.

The impacts last for numerous generations. Not only do the children of more educated mothers do better, but their grandchildren and great grandchildren also do better. On the other hand, malnourishment during the first 1,000 days is linked to low education and economic opportunity for the child. It can result in daughters getting pregnant earlier and having less healthy children. This vicious circle can continue for generations.

How does Mexico stack up with other major countries around the world? The results for Mexico are a bit mixed. From 1990 to 2010 Mexico recorded an impressive decrease in malnutrition of 3.1% per year. (The measure of malnutrition used in this comparison was children too short for their age, “stunting”). Mexico has cut malnutrition almost in half (47%) since 1990. This decrease ranks it 11th among the 165 countries analyzed. Much of this progress is associated with Mexico’s Oportunidades Program. The ten countries that did better than Mexico include China (6.3%), Brazil (5.5%), and Vietnam (4.3%). Fifteen countries suffered increases in malnutrition during the 20 year period, including Somalia (6.3%/year), Afghanistan (1.6%/year) and Yemen (1.0%/year).

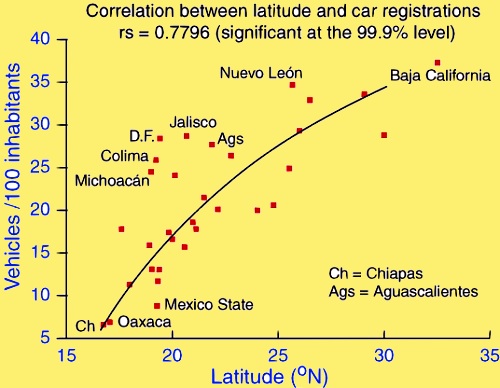

On the other hand, the study points out that, given its level of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, Mexico’s level of malnutrition is higher than it should be. Other under-performers include the USA, Singapore, India, Indonesia, Guatemala, Peru, South Africa and Venezuela. These countries tend to have very inequitable distributions of income. Surprisingly, Brazil, with one of the worst levels of income inequality, was among the group of countries with lower malnutrition than expected given their GDP per capita. Other over-performers include Chile, Ukraine, China and Vietnam. Obviously, in all countries malnutrition is much worse among the poor.

The study divides the 165 countries into the three Tiers used by the United Nations. The Tiers are labeled I-“more developed”, II – “less developed” and III – “least developed”. Tier I is limited to Japan and European countries. Mexico is one of 80 countries in Tier II (“less developed” countries).

The UN has a “Women’s Health Index” for Tier II, comprised of lifetime risk of maternal death, percent of women using modern contraception, percent of births attended skilled attendant, and female life expectancy at birth. Within this group, Mexico ranks 19th in “Mother’s (Health) Index” compared to Cuba (ranked 1st), Argentina (4th), Brazil (12th), China (14th), South Africa (33rd), Turkey (47th), Iran (50th), Philippines (52nd), Indonesia (59th), Saudi Arabia (63rd), Egypt (65th), Guatemala (68th), India (76th), Pakistan 78th) and Nigeria (80th).

The differences between ranks appear to overstate the real differences. For example, the scores on the individual variables for Mexico (19th) and Argentina (4th) are relatively close. The chance of maternal birth-related death is one in 500 for Mexico versus 600 in Argentina. In Mexico 95% of births are attended by a trained worker compared to 98% in Argentina. Two thirds (67%) of Mexican women use modern contraception methods compared to 64% in Argentina. Life expectancy for women is 80 years in both countries.

The UN “Children’s Health Index” for Tier II is comprised of under age five mortality rate, percent of children under 5 moderately or severely underweight for age, gross primary enrollment ratio, gross secondary enrollment ratio and percent of population with access to safe drinking water.

Mexico ranks 18th among Tier II countries in terms of “Children’s (Health) Index” compared to Cyprus (1st), South Korea (2nd), Brazil (7th), Argentina (8th), Turkey (10th), Egypt (21st), Iran (26th), China (34th), South Africa (56th), Guatemala (63rd), Philippines (64th), Indonesia (70th), Pakistan (76th), India (77th) and Nigeria (82th). Here again, the differences between ranks appear to overstate the real differences.

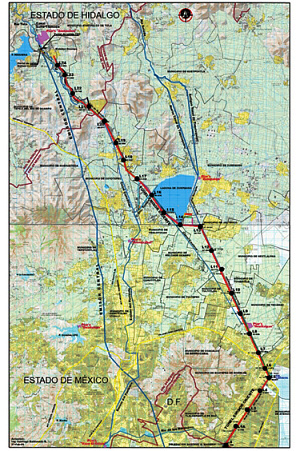

While Mexico has made impressive progress concerning mother’s and baby’s health, it still lags behind Argentina and Brazil not to mention virtually all European countries. The biggest concern is rural areas of Mexico, especially southern Mexico, which seriously trail urban Mexico in terms women’s and child’s health. For example, infant mortality rates are highest in Chiapas, Oaxaca and Guerrero, followed by Veracruz, Hidalgo and Puebla. On the bright side, rural areas are making great progress thanks to programs like Oportunidades.

Happy Mother’s Day!