Africanized honey bees, sometimes popularly called “killer” bees, resulted from the crossing (hybridization) of European honey bees and African honey bees. They combine the best and the worst of both sets of relatives. Africanized honey bees are slightly smaller than European honey bees, but more aggressive and less inclined to remain in one place. They can swarm and attack even if unprovoked, even though they can sting only once before dying shortly afterward.

Their “killer bee” label is because they have killed 1,000 people in the Americas since their ancestors escaped from a laboratory in Brazil. Africanized bees react ten times faster to disturbances than European bees and can pursue a hapless human victim for 300-400 meters.

The mixing of genes that created Africanized honey bees occurred in the 1950s. In 1956, Dr. Warwick Kerr, a bee researcher in Brazil, hoped to develop a bee that would thrive in Brazil’s tropical climate. He decided to cross European bees with African bees. Unfortunately, in March of the following year, some of his experimental bees escaped into the wild. The Africanized bees soon began to multiply and expand their range. They proved to be very adaptable, and have since spread, at a rate of up to 350 km/year through most of South and Central America, as well as into Mexico and the USA. They arrived in Peru by 1985 and Panama by 1982. Their spread northwards continued, and they crossed from Guatemala into Mexico, near Tapachula, in October 1986.

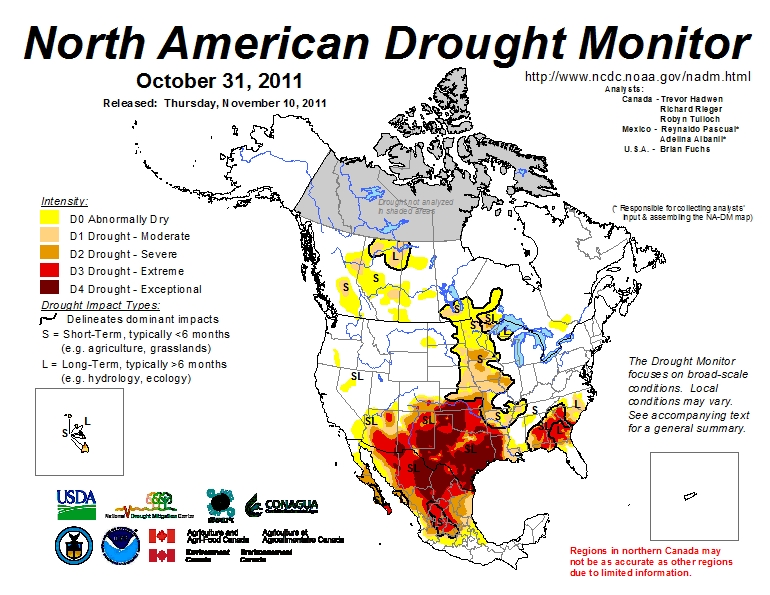

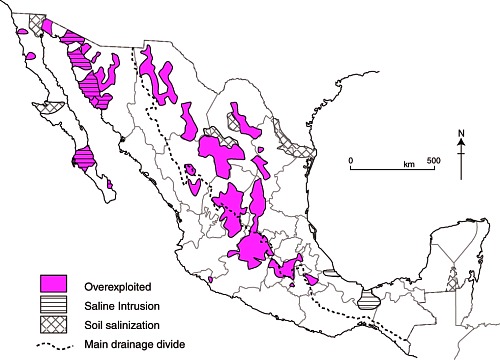

The map shows the gradual northward spread of Africanized bees in Mexico. Up to 1987, the progression looks fairly regular, but in the following year, Africanized bees’ northward movement was restricted to a zone along Mexico’s Gulf Coast. This remained true even through 1989. By 1990, the “front” of the bees advance once again stretched right across the country.

Q. What factors may have caused the unusual (anomalous) geographic spread of Africanized bees in 1988 and 1989?

Africanized bees spread across Mexico (adapted from Kunzmann et al)

Why are Africanized bees more migratory than European bees?

Scientists believe that Africanized bees are uniquely equipped to cope with the unpredictability of suitable food sources in the tropics. They are more opportunistic, changing their foraging habits to suit local conditions, including short-term supplies of pollen, which they will collect and store to ensure their survival. When a new resource presents itself, Africanized bees will swarm rapidly to maximize their use of the new pollen source.

In bio-geographical terms, Africanized bees are an example of an opportunistic or r-species, perfectly equipped to move to new or changing habitats. They reproduce rapidly, and use available resources efficiently. This makes them far less stable than European bees which thrive in a more predictable environment and adapt to changing circumstances far less quickly.

Africanized bees can survive on limited food supplies, will explore and move to new locations frequently and are aggressive in defending their resources. When they come into contact with other less aggressive bees, such as Mexico’s native bees, Africanized bees may out-compete them for pollen and eventually replace them as that area’s dominant bees.

In Mexico, the speed of diffusion of Africanized bees slowed down

When Africanized bees were reported from southern Mexico, US beekeepers began to fret. The US honey industry is worth 150 million dollars a year. Fear spread that Africanized bees might jeopardize the entire industry, mainly because they are prone to migrate, and would be hard to control.

US experts helped finance a joint program in Mexico which aimed to slow down the bees’ progress northwards. The original idea was to stop bees from crossing the narrowest part of Mexico, the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, preventing them from reaching central Mexico. However, by the time funding was approved, some bees had already crossed the Isthmus. The focus of the bee-control plan was changed to trying to slow down their seemingly inexorable progress north. Even if scientists could only delay the bees’ progress, it would give US farmers more time to plan for their eventual arrival.

The plan was relatively simple. Hang sufficient bee traps in trees throughout the region to attract wild swarms while banning Mexican beekeepers from moving any hives from southern Mexico into central or northern Mexico. Thousands of distinctive blue boxes appeared in orchards and forests across a broad belt of Mexico, from the Pacific to the Gulf.

The combined Mexico-US program is credited with having slowed the bees’ entry into the USA down by about two years. Even so, by 1990, Africanized bees were spotted in Texas; they reached Arizona by 1993 and California by 1995. By this time, they were also found throughout Mexico.

In a later post, we will look at honey production in Mexico and see whether or not it was permanently affected by the influx of Africanized bees.

Sources:

(a) “Africanized Bees in North America” by Michael R. Kunzmann et al, in Non-native Species by Hiram W. Li (biology.usgs.gov)

(b) Introduced Species Summary Project: Africanized Honey Bee by Christina Ojar, 2002.

(c) Alejandro Martínez Velasco. Las andanzas de la Abeja Africana Informador (Guadalajara daily), 1 September 1991.