“Holiday in Mexico” is a collection of essays relating to the history of tourism in Mexico. The dozen authors involved are primarily academic historians, but also include a journalist. While the writing style is somewhat varied, this in no way detracts from the overall high quality of the contributions.

As Dina Berger and Andrew Grant Wood, the book’s editors, point out in their introduction, Mexico’s dilemma as regards tourism has always been to “reconcile market demand with a desire for national sovereignty” (p. 1). Tourism may stimulate the economy but can also have adverse environmental, social, and cultural consequences. Tourism promoters have always sought to “package” Mexico in a way that will attract tourists. The tourism sector’s portrayals of Mexico are inevitably subjective and seek to influence the perceptions of potential visitors.

The book’s 14 chapters (including the introduction) span 3 time periods:

- 1840s-1911

- 1920-50

- 1960-present

and examine three main themes:

- how Mexicans promoted and imagined their country and culture

- the political lenses through which Mexicans and tourists have interacted with each other

- the advantages and disadvantages of tourism

1840s to 1911

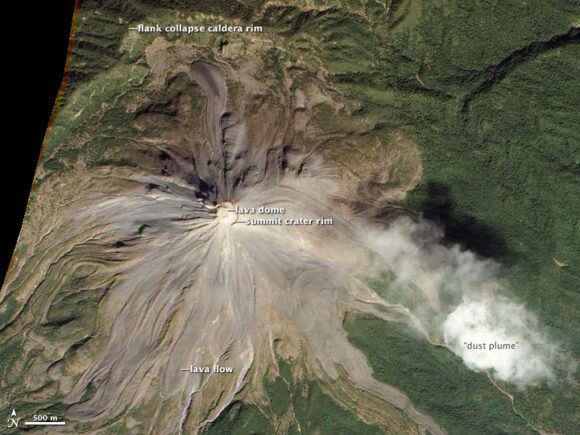

Two chapters look at the early history of tourism in Mexico. Andrea Boardman links the early days of American tourism in Mexico to the US soldiers who entered Mexico during the Mexican-American War. Among other achievements, American soldiers climbed Mexico’s highest peak, El Pico de Orizaba, though they were certainly not the first foreign nationals to do so. The accounts written by soldiers helped the American public appreciate that Mexico was worth exploring. Visiting Mexico became easier once the major railway lines had been completed at the end of the nineteenth century.

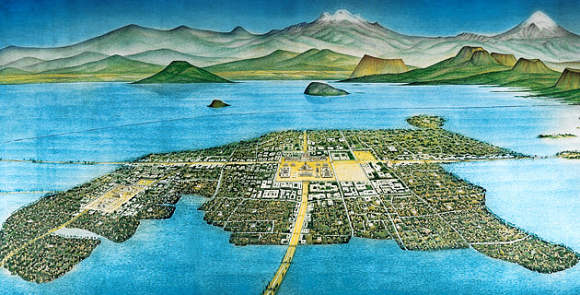

Christina Bueno offers a detailed look at the contested reconstruction of Teotihuacan, the earliest major archaeological site to be opened for tourism, its “restoration” timed to coincide with the celebrations for Mexico’s centenary of independence. Cultural and historical tourism have remained important aspects of tourism in Mexico ever since. Such tourism simultaneously stresses the significance of indigenous culture while portraying the nation as “modern” and “forward looking”.

1920-60

Five chapters of “Holiday in Mexico” look at the formative period of tourism development in Mexico that began shortly after the start of the Mexican Revolution in 1910.

Andrew Grant Wood shows how business leaders in the port of Veracruz were able to reposition the city, changing its image from an insalubrious and unsafe city into a haven for cultural activities, music and dance, centered on annual Carnival celebrations.

Andrew Grant Wood shows how business leaders in the port of Veracruz were able to reposition the city, changing its image from an insalubrious and unsafe city into a haven for cultural activities, music and dance, centered on annual Carnival celebrations.

Dina Berger looks at tourism, diplomacy and Mexico-USA relations. Mexico’s active promotion of its national progress (such as modern highways), democracy and friendliness coincided with a period when the USA pursued its Good Neighbor policy and Panamericanism (such as the construction of the Pan American Highway).

Eric Schantz’s essay focuses on postwar tourism in Baja California’s border zone, and considers the impacts of gaming, racing, prostitution and the growing tourism entertainment industry. Many of those crossing the border to partake in these activities were, strictly speaking, “visitors” rather than “tourists”, since they remained less than 24 hours, but they had a massive influence on the economy of some border cities.

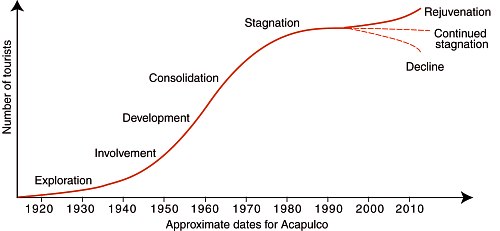

In the next chapter, “Fun in Acapulco? The Politics of Development on the Mexican Rivera,” Andrew Sackett weaves a carefully-crafted narrative that encompasses Acapulco cliff divers, Hollywood movie stars, state intervention, poor ejido farmers being dispossessed of their land, and the capriciousness of resort developers. This is possibly the strongest chapter in the book from a geographical perspective, though Sackett overstates the significance of a 1946 map of the city, since all maps are perceptual statements and necessarily simplify the landscape and select the most appropriate points of reference for their intended audience.

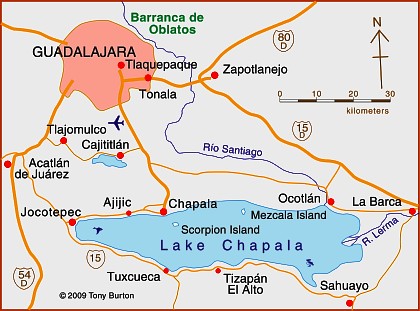

Lisa Pinley Covert then looks at how San Miguel de Allende’s tourist industry developed from a combination of local, national and international factors and players. In this case (unlike Acapulco) local efforts were preeminent in establishing the city’s reputation as a center for cultural tourism. Interestingly, no distinction is drawn in this chapter between the impacts of “tourists” and the impacts of the longer-term, non-tourist foreign residents that now comprise a distinctive segment of the city’s population.

1960-present

The final five chapters have greater contemporary relevance. Jeffrey Pilcher gives an engrossing account of how culinary tourism emerged, of how restauranteurs created “authentic” Mexican cuisine, a kind of “gentrification” of Mexican food. This account supports the view that cultural imperialism has not led to the food homogenization of North America, but, on the contrary, has led to varied, glocalized responses including innovatory regional and local cuisine.

M. Bianet Castellanos looks at the lesser-known face of mass tourism in the centrally-planned FONATUR resort of Cancún: the many service workers who migrated from nearby indigenous communities, and their perceptions of the resort and its tourist industry.

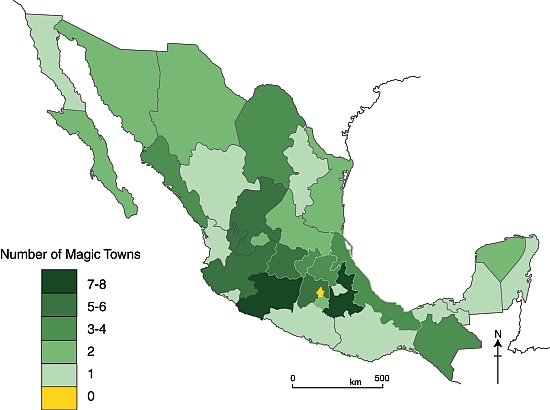

Adopting a national viewpoint, Mary K. Coffey examines how federal government policies in the past decade or so have sought to promote Mexico’s artistic and folk art culture as a powerful magnet for tourism. To remain competitive on the world stage, and counteract the impacts of events elsewhere (such as 9/11), Mexico’s tourism sector needs to continually reinvent itself. This is an excellent example of how changing policies and rhetoric can help keep Mexico in the world tourist spotlight.

In looking at Los Cabos, another centrally-planned resort, Alex M. Saragoza emphasizes how it was designed specifically to appeal to wealthy US tourists, hence its emphasis on golf courses, and its grandiose plans (now scaled-back) for the “Escalera Náutica”, a network of marina resorts.

The final essay, by travel writer Barbara Kastelein, looks at some of the forces behind the development of tourism in three contrasting locales: Acapulco, Oaxaca and Amecameca, considering some of the broader aspects including race, gender, and class dynamics.

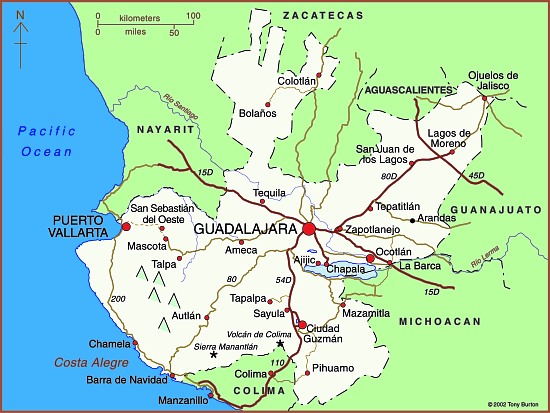

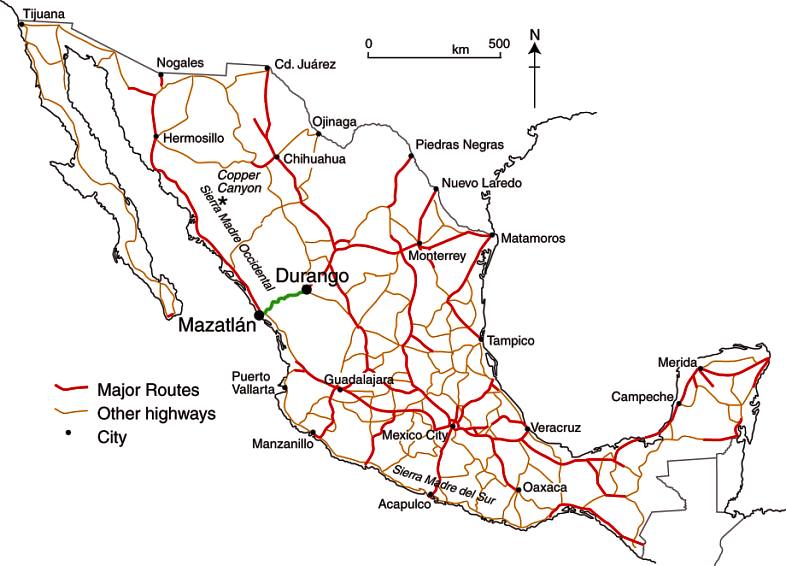

The geographical coverage of “Holiday in Mexico” is quite broad but certainly not comprehensive. The use of case studies allows the authors to explore the many subtexts in depth, but it may be that some of the insights arrived at fail to hold up when a regional or national scale is considered.

The book certainly provides plenty of ideas worth further discussion, along with thoughtful analysis of different stakeholders, different types of tourism and their relative merits. The authors do not shy away from looking at the impacts of the massive socioeconomic gaps between tourists and their Mexican hosts, or of the corruption that has unfortunately accompanied many tourism developments in Mexico.

If I have one minor reservation about this book, it is that it is overly US-centric. The history of tourism in Mexico deserves a more nuanced approach, one in which the role of European and Latin American tourists is also closely examined. This clearly opens up many possibilities for future research.

Dina Berger and Andrew Grant Wood (eds). 2010 “Holiday in Mexico: Critical reflections on tourism and tourist encounters.” Duke University Press.

Related posts:

- Rose Georgina Kingsley (1845-1925)

- The growth of Cancún, Mexico leading tourist resort

- San Miguel de Allende: the “world’s best city”?

- An early ascent of Mexico’s highest mountain, El Pico de Orizaba

- The cultural geography of Mexico’s carnival celebrations

- Did You Know? Famous artists pioneer art community in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico

- Review of Jeffrey M. Pilcher’s “¡Que vivan los tamales! Food and the making of Mexican Identity”